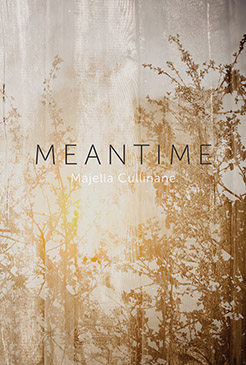

Meantime, Majella Cullinane, Otago University Press, 2024

Could I tell you I wish you could see this sky?

We could sit on the deck.

Ignore the overgrown clematis—I’m not much of a gardener.

I wish I could speak to you

but I don’t understand the language of the dead.

Stay here and watch with me.

Watch the sky shift from flaxen to coral to mauve

And, as the minutes pass, to muted grey.

Let’s watch with the door open for the light to go.

from ‘Stay here’

Most reviews I write, draw upon the idea that to review a book is to re-see a book, to return and let the multiple lights and darknesses settle upon me. To try and leave my reading baggage and expectations at the backdoor step and enter the myriad delights of discovery. Heaven forbid if I am travelling with notions of what a poem ought to be or not to be, or notions that subject matter can be old hat or redundant. I have read so many extraordinary poetry collections over the past year (perhaps this is an example of post-transplant awe and wonder) and this week, having read, and reread Majella Cullinane’s glorious Meantime, I am taking stock of myself as reader and reviewer. Firstly, I am drawn to the heart of a poem, the heart of a book. I am picturing a core organ that promotes rhythm, energy, reading blood flow, along with ideas, sensations, feelings. I am curious about the alchemy of elements and the effects that set you alight and comfort and delight as you read. A good book of poetry is like an effervescent tablet in the heart.

Majella’s new poetry collection is exactly this, an effervescent tablet in my heart – it is a jolt, a boost, a sparkle. Majella writes out of grief, mourning her mother who died in Ireland when the poet was trapped in Aotearoa due to the Covid lockdown. Writing becomes a form of speaking, poetry a way of talking to and of and for her mother, and it is so very intimate, this maternal portrait, this daughter speaking. Mother missed and missing, perhaps too, daughter missed and missing. Fugitive memory. Necessary memory.

I am drawn to the unstable ground of writing, to the section titles that underline a fragility of being: ‘Am I still Here?’, ‘Meantime’ and ‘Nowhere to Be’. Writing becomes a way of retrieving elusive memory but also way of replenishing the gap, between here and there, Aotearoa and Ireland, life and death, mother and daughter, what is said and what is not said, what is safe and not safe and, in the context of a mother who is suffering from a form of dementia, what is delusional and what is real.

The sight of the pīwakawaka in the opening poem, ‘Memory’, is fitting. Its tail flickers like memory, like the unspoken, the subtly referenced: ‘Quiver / of pīwakawaka tail / hide / and seek’. Move to the final lines where the ‘d’ word cannot be spoken, and the poet muses on elusive memory:

one day

I might

be the old woman

who doesn’t remember

walking into a room

and asking—

whose memory

is this anyway?

The pīwakawaka sighting is also a vital marker of place, giving shape and physicality to the elsewhere of here. Majella plants physical anchors, from the ‘tūī song’ to the ‘korimako in the neighbour’s oak tree’ as she listens to her mother’s favourite music. Again, a quiver between dream and wake, between here and there, moving among poignant images, the near past, the distant past, the mother ghost haunting rooms, objects, the preparation of food.

From the dark hall I see your ghost

standing at the kitchen table.

Your hands are dusty with flour, your sleeves rolled up.

You ask me how my day has been.

What do I say on this first day of winter?

I watched two pihipihi fly into a sunlit tree,

a tūī sip water from the neighbour’s eave.

I walked to the local bay and barely noticed the ocean.

from ‘Winter recipe’

Majella draws her mother into the folds and crevices of her homesickness and heartache, into her daily movements and her recognitions. And it is tribute and testimony and self care.

More than anything, Meantime is poetry at its most intimate, movingly so, and as readers we get to share in that intimacy. We might sidestep to our own trembling ground, our own losses and aches. We might pause to absorb a volley of grief and a shawl of comfort. I love this collection so much. I love its gentleness, its exposures, its pain and its healing. And above all, its love.

A reading

Majella reads ‘Nowhere to be’

Majella reads ‘Meantime’

Three questions

What are three or four key words for you when you write poetry?

Listening, quietness, absence/presence

What gave you particular joy when you wrote this new collection? Or challenge?

I wrote the collection over a period of multiple Covid-19 lockdowns (2020-2022) in New Zealand. During that time, I was grieving my mother who died during Ireland and New Zealand’s first lockdown in April 2020. Grief affects a person mentally and physically, but writing and reading poetry and essays during this time was a huge salve.

Have you read any poetry books in last year or so that have struck a chord?

Seán Hewitt’s poetry collections: Tongues of Fire and Rapture’s Road

Iona Winter’s A liminal Gathering – Elixir and Star Grief Almanac 2023

Geraldine Meaney’s Mute/Unmute

The late John Burnside’s Selected Poems

Kerry Hardie’s We Go On

Vincent O’Sullivan’s Selected Poems: Being Here

Majella Cullinane writes poetry, fiction and essays. Her second collection Whisper of a Crow’s Wing (Otago University Press and Salmon Poetry, Ireland) was chosen as The Listener’s Top Ten Poetry Books of 2018. Her writing has been published internationally, and she has held residencies and fellowships in Ireland, Scotland and New Zealand. She was awarded a Copyright Licensing New Zealand Grant (2019) and a Creative New Zealand Arts Grant (2021) to complete Meantime. She graduated with a PhD in Creative Practice from the University of Otago in 2020. She lives in Kōpūtai Port Chalmers with her family.

Otago University Press page

Pingback: Poetry Shelf newsletter | NZ Poetry Shelf