The Spin Off recently posted a terrific series of tributes to Geoff Cochrane. His passing has saddened so many readers and writers; social media is evidence of the depth of feeling for Geoff, for his writing, his presence on our literary landscapes. I invited his publisher Fergus Barrowman, his publicist Kirsten McDougall, along with writers Anne Kennedy, Chris Tse and Pip Adams to select a poem by Geoff that they loved. We have all been reaching for his books on our shelves, to settle into a poem, to grieve and to celebrate.

Damien Wilkins once wrote: ‘Geoff Cochrane’s is a whole world, rendered in lines at once compressed and open, mysterious and approachable.’

In my NZ Herald review of Pocket Edition (2009) I wrote: ‘Cochrane’s mix of dark, witty, concentrated lines are well worth storing in a jacket pocket for the spare little moments that beg for a poem.’

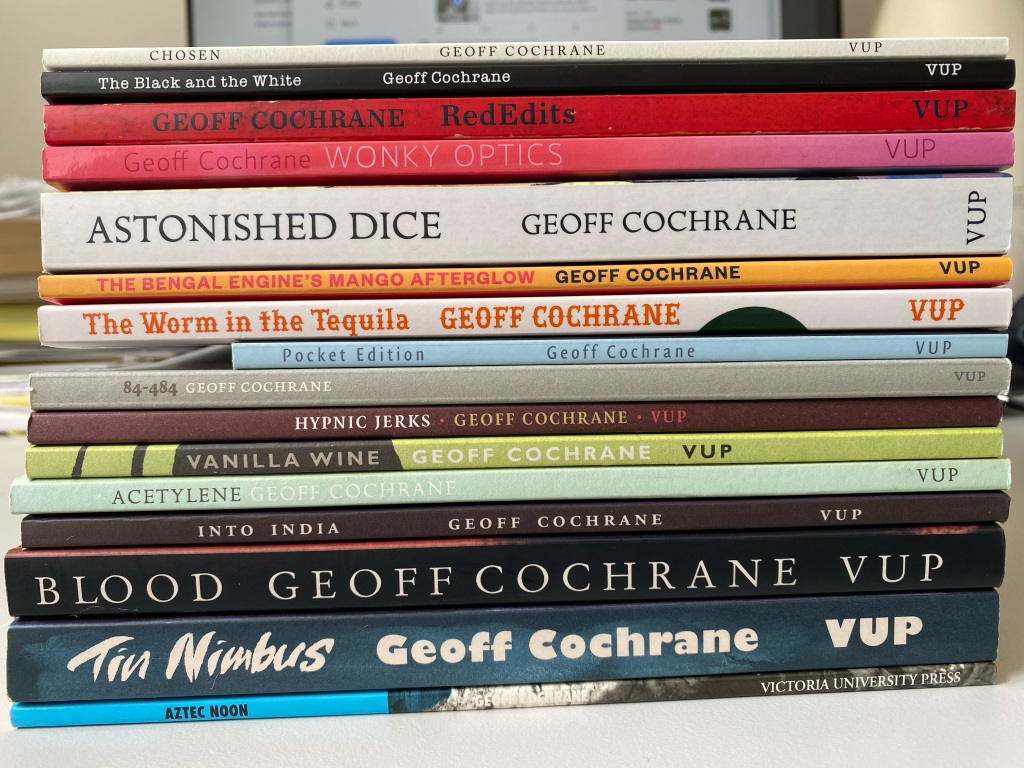

Geoff was the author of 18 collections of poetry, mostly recently Chosen (2020), two novels, and Astonished Dice: Collected Short Stories (2014). In 2009 he was awarded the Janet Frame Prize for Poetry, in 2010 the inaugural Nigel Cox Unity Books Award, and in 2014 an Arts Foundation of New Zealand Laureate Award.

An Ambulance

Between hospital and zoo

asterisks of rain fall audibly

on the many old tin awnings.

Through cool blue air arrives

a siren’s pure ambulance. Someone

is dying of too much afternoon,

of fennel and cats and clothes props.

Geoff Cochrane from Aztec Moon (Te Herenga Waka University Press, 1992).

Selected by Fergus Barrowman: This poem has everything I love in Geoff’s work. It was the second poem in the manuscript of Aztec Noon, and the moment of encounter and recognition remains vivid 30 years later.

3 : 00 A. M.

The wind at night is new

The wind at night is black and unadorned

The wind at night is better than other winds

Step outside and taste it

Step outside and feel it on your face

The wind at night is clean

The wind at night is lucky

The wind at night is young, innovative

Step outside and taste it

Step outside and feel it on your face

Geoff Cochrane from The Bengal Engine’s Mango Afterglow (Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2012)

Selected by Chris Tse: Geoff was the master of capturing the fleeting moment. Many of his poems were short bursts of clarity behind those daily interactions and pauses that often pass us by without a second thought. I chose this poem because I know that early morning wind well – it’s been both confidante and unruly friend. I only ever met Geoff once, very briefly, but I’ve met him hundreds of times over on the page.

The Rooming-House

1

An ambulance might splash

its scarlet light about.

The concrete steps and paths

were mounded and Pompeian,

like fluid porridge frozen;

Do Not Leave Chotes To Soke read the card

in the cold, spacious, primitive laundry.

2

When I got a room at last, it was tiny.

Tiny and quiet, with a wee built-in bookcase

in which I installed

a radio and a dictionary.

And I sat side-on

to my little olive desk

and drank and drank my plonk

a little at a time,

like a student of something large and long,

large and long and complacently abstruse.

And many nights fell

and many days dawned,

and I studied and studied.

3

An ambulance might splash

its scarlet stain about.

My bedding was arranged

neatly on the floor,

but my sherry glass got very

cloudy, grubby, gooey, its utility contingent

on its never being washed.

Yes. And what I was after,

what I sought to renew day after day

and night after night

(tried to understand by reinforcing),

was the gorgeous condition of being

addicted to addiction.

Geoff Cochrane, from The Worm in the Tequila ((Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2010)

Selected by Anne Kennedy: In this poem, Geoff shows everything to do with the room: outside the room, inside the room, the poet in the room, the reader in the room. The intense emotion in the room is so recognisable yet completely original. How does he do this? I don’t know!

Super Wine

The news is early or his clock is slow,

so he grabs his mug of tea and pops

a biscuit in his pocket,

the top pocket of a faded old coat.

It’s a wreck of a thing, this coat of his.

a shamefully limp and grubby article,

but he wears it through the news and Campbell Live

and on into the night,

and he wears it when he leaves his little flat

and slips up the lane and out into the park

and lights a cigarette

(his skinny nine-o’clocker

and the last of the day).

And he smells the smells of mown grass and woodsmoke,

and he walks across the park towards the lights,

the lights of the houses on the hill,

secular stars of silver and orange,

and he walks beneath the frosty stars themselves,

this unmarried, unmended man,

this unmarried, not-unhappy Earthling,

A Super Wine forgotten in his pocket.

Geoff Cochrane

from Pocket Edition (Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2009)

Selected by Paula Green: I love how Geoff’s poem draws me into the throat, heart and resonance of the present tense, the evocative detail sharp, the biscuit embodying so very much. The last line always gets me.

Impersonating Bono

for my sister Mary

On a bright, crisp day in winter,

we leave our mother’s house to walk to town.

You seem proud of me. Or unashamed. Which is better.

You hook your arm through mine and we are sweethearts.

Petite and fresh, you’re over from Australia.

Left to my own devices,

I’d walk as far as the old railway station,

passing the junk shops and the new green tractors,

the saddlery with the plastic horse on its awning.

But not today, for today I have you on my arm.

Our jaunty tour takes in

the carpeted mall, the TAB Dad ran,

the library in which you once worked.

In Paper Plus, we score a couple of Little Golden Books

to give to Luke at his christening brunch

(the reason for our unseasonal reunion).

I’ve left my shades in Wellington.

You talk me into buying

a replacement pair at the $2 Shop–

slittishly repulsive retro jobs

through which the cheapened world looks sick and blue.

Geoff Cochrane from Vanilla Wine (Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2003)

Selected by Kirsten McDougall

Little Bits of Harry

chapter i

The Marmitey smell of a roast.

Harry watched his Grandad crank the table.

June could do with a spot and Here’s to your very good health.

chapter ii

He was raised not far

from a salt-and-vinegar beach.

The wound in his shoulder looked like a slitty eye.

chapter iii

Harry had a friend called Brian.

Brian’s smile was framed by inverted commas (“v”).

Together the boys made poisons,

decanting their grassy sauces

into Aspro bottles shaped like canteens.

Under the house was where

they’d built their Zombie Chair.

And under the house was where they stored their poisons,

smoked cigarettes and cultivated stiffies,

tent-poled their school shorts with stiffies (“v”).

chapter iv

Trust Harry to do a lovely Jesus.

To get himself nailed up

with many a fine contortion and grimace.

(The theme from Exodus played.

Brian’s Roman helmet had been painted

with gold paint from the hardware.)

chapter v

Harry’s father loathed Mario Lanza.

The cold yellow sky dimmed to mustard.

Rain swept up the valley, crowding it like troops.

chapter vi

Winter seemed to mirror

the sweet rainy gloom

in Harry himself.

Nanna sat in front of the fire,

toasting her shins and listening to the footy.

Harry sprawled beneath her, in the odours of crumbling heels,

mottled calves and droopy puce stockings.

And the wound in his shoulder began to squeak,

squeak and whistle like the fire itself.

Like the fire in which the damned were said to live,

their hot bodies molten orange jellies.

chapter vii

“That’s it,” said Harry, vexed. “I’m setting my face

against it all.”

“What about your passion-plays and poisons?”

his mother asked.

“I’m setting my face against it all. All except swimming and

going to the pictures.”

“Well that sounds mighty fine, but what about the dental

clinic? You won’t get very far setting your face against the

dental clinic, however implacably.”

And when he got to the brilliant, methylated clinic,

he was sent straight home again

for having furry teeth.

“I’ve disgraced us both,” Harry told his mother.

“And how,” said she. “Get in there and polish good,

you fiend!”

chapter viii

The wound was like an eye.

Or a slitty, sticky mouth.

Whether eye or mouth or merely perennial gash . . .

chapter ix

Harry’s father managed

a radio shack in Furnace Lane.

And Harry liked the murk,

the smelly alchemy of his old man’s profession.

There were fresh boxed valves in pigeon-holes

and chassis labelled like toes in a mortuary.

And Harry was thrilled by the tinny stink,

the runny splash and flash,

the quicksilver dartings of the solder.

By the bevelled tongue of the iron, so hotly blued

and silvered.

“The secret of good soldering

is to work cleanly with clean surfaces,”

Harry’s father explained.

And handed his son a slimmish book: Radio for Boys.

chapter x

College. Saint Cuthbert’s was a place of “standards”.

Of lines to be toed and traces

not to be kicked over.

Larking near the milk float merited a flogging.

There was also a mysterious urinal

juniors were discouraged from using.

When Harry ventured into it,

he got what almost amounted to a fright.

The gorgeous prefect Harry encountered within

had long-lashed, Ray Liotta eyes

and a dingy, ancient, ox-felling cock.

A veritable Trojan of a tool, but modelled in accordance

with the slickest principles of modern rocketry.

chapter xi

Each year began with the soapy odour of newly purchased

exercise books. The chaste white leaves of which seemed to

offer scope, to promise better academic results. It was never

long, however, before Harry had begun to fill his books with

circuit diagrams and sketches of inventions. With red stanzas

shaped like expensive bits of advertising copy.

chapter xii

Brass band. Choir. Drama club.

Harry tried them all, only to find himself

underemployed and bored.

And then would come the warm messy business

of withdrawal, disengagement.

The qualified disgrace of having to return

the flugelhorn whose valves had kept sticking.

chapter xiii

Firemen pumped Saint Cuthbert’s flooded basement.

In library and classroom, flubby gas burned pinkly.

And the body of a pupil killed in a car crash

was laid out in the chapel.

And the guy looked most peculiar,

bounced sideways into death,

like some rouged harlot lividly contused.

Like some rash pierrot mauled

by the colours rose and mauve.

chapter xiv

A morning, yes, in spring.

But Saint Cuthbert’s lay in ruins,

Saint Cuthbert’s had been crunched.

A haze of smoke and dust

hung above a hill

of shattered grey masonry.

Puny yellow fires devoid of any briskness

licked up through the rubble here and there.

I loved it but it didn’t love me back, thought Harry.

It failed to apprehend the qualities in me,

the excellence of me and my lambent wound.

chapter xv

Or were the failures and derelictions mine?

But were they?

chapter xvi

Parks and public gardens became his haunts,

a limp oilskin parka his cloak.

In a stately filmed ascension screening backwards,

he was sinking to the bottom.

chapter xvii

He’d noticed a dank garage

up near the old tram tunnel.

Seepage and stink and frog-green slimes:

no one had used the place in years.

And Harry took his fish and chips in there,

his library books and cartons of flavoured milk.

And the hip, punchy novels of P. Zanoski

got into his blood like a craze,

a suave new malaria

sexy as ejaculate.

chapter xviii

The odour of a sump or an oily grave. But Harry rehabilitated

a manky chair he’d found (so that then he had a seat). And

he stole a couple of P. Zanoski’s books and fashioned a shelf

for them (so that then he had a bookcase). And Harry liked

to imagine P. Zanoski flying in from Chicago. Sending one

of his minders ahead of him. “P. Zanoski will be here in two

minutes. He’ll accept a cigarette, but please don’t offer him

gum.” The white gleaming limo just outside, soon to be

joined by a second and a third.

chapter xix

The telly he salvaged from the skip? The telly he salvaged

from the skip was a small girly number with a plastic cabinet

of cream and lipstick-red. It needed a few modifications,

sure, but Harry worked for hours to convert it into a sun-

lamp, and soon he had his contraption up and running. And

he’d spin the bicycle wheel that juiced the system, strip to

the waist and sit in front of the screen. Certain dormant

circuits would thaw and kindle, and the charcoal screen

would glow invisibly, pumping forth a torrent of black light,

black influence, black medicine. And the wound in Harry’s

shoulder could begin to heal at last. Could begin to shrink

and close—or seem to.

chapter xx

Unworried sleeplessness.

Engagement with the texture of the moment.

For the treatments had their novel side-effects.

A good dose of the sun-lamp

imbued him with an energetic bliss,

a wakeful equilibrium,

a rapturous serenity abiding.

Yes.

A single hit of darkest radiance

and Harry was pumped for days.

Wired and feeling like

a crystal ping sustained.

chapter xxi

Night’s brassy shadows.

The flimsy Chinese carpentry of night.

And Harry out walking all the time,

working off his treatments at all hours.

chapter xxii

They stopped him outside the electricity park, that buzzing

necropolis of cottage-sized transformers and giant porcelain

peppermints.

The car drifted in toward the kerb like a flying saucer on its

best behaviour. “What. You couldn’t sleep?”

“Something like that,” said Harry.

A golden-haired forearm. The dashboard’s toxic purple array.

“Hop in,” said the cop, “it’s fun in here.”

“Like Der. Like Let me think.”

“You’re a healthy looking kid. And a smart one too I’m told.”

“So?”

“So give your folks a ring. They’re worried sick. I speak to

you again I better hear you called.”

chapter xxiii

Weeks passed. Months.

While slowly the sun-lamp’s dark effulgence

seemed to dwindle in potency,

so that Harry needed more and more of it.

And then, while he was out,

the garage was trashed.

The bicycle wheel wrenched from its cradle.

The telly’s ham-shaped tube bashed in

and its fragrant pastel gasses dissipated.

chapter xxiv

Slipping his P. Zanoski books

into his khaki bag,

he traipsed across the city.

Cowled and caped in blankets,

he hunkered down beneath the motorway.

A spitty wind blew up.

The sky was a fuzzy orange murk.

And it rained on our dispirited Harry,

on Harry and his army-surplus knapsack.

chapter xxv

He took to drinking cough mixture. Sometimes he was asked

to sign for it. “Blaise Cendrars”, he’d put. “Blaise Cendrars”

or “Alexander Trocchi”. And he’d get through several bottles

in a day. Three or four bottles, yes.

chapter xxvi

He’d often breakfast at the soup kitchen (a statue of the Holy

Family presided. The soup came in stainless-steel jugs) and

there he met a chick who took him aboard a ship.

In a grotty cabin charged with a greeny stench (some sturdy

distillate of marine putrescence?), he gave her the business

well and truly. “Great,” she said, “and you so long and thick!

Do you always keep your shirt on?”

“It’s gelid as, down here.”

“Give us a swig of your syrup, there’s a pet.”

chapter xxvii

3 a.m. A brilliantly fluorescent service station. Harry had

scored a cappuccino (he craved the milk, the sugar) and was

stirring it with a small wooden stick.

“So how the fuck’s it looking?” asked the stranger.

Harry shrugged. “Like where do I go to sell my blood?”

“You don’t do that. You make another plan.”

“Yeah?”

“Sure.” The stranger winked and popped his can of Pepsi.

“Stick with me and I’ll get you hung.”

“The word you want is hanged. Stick with me and I’ll get

you hanged.”

“Hanged. Hunged. Whatever.”

chapter xxviii

His name was Rubin.

A little tee-shaped chalice of a tuft

adorned his lower lip,

and he wore a long black leather coat

in which he looked agreeably satanic.

chapter xxix

He was staying at the swanky Xanadu. “Temporary riches,”

he explained, “—a winning streak at blackjack.”

Carpet. Tepid musks. An elevator prescient and swift, below

the perspex capsule of which the twinkling city was spread.

And Harry saw the city and the world (a doomed winter

festival of lights) fall away from under the rocket.

chapter xxx

Rubin’s suite was warm, its colours peach and beige. Rubin

himself had hired the ecclesiastical jukebox with its rainbow

of glows.

Harry took off his parka. Unbuttoned the cuffs of his shirt

and sat down on the sofa. “I could get used to this,” he said.

“You reckon?”

chapter xxxi

When Harry produced his bottle of cough mixture, Rubin

scoffed. “Say goodbye to that crap. Let me give you a taste of

something decent.”

He tied off Harry’s arm with a rubber tourniquet. And slid

the needle into Harry’s vein adroitly, painlessly.

“You’re being very . . . doctorly.”

“I keep it dark, but I almost qualified.”

“And I won’t need the linctus anymore?”

“You won’t need the linctus. Nor any fucking sun-lamp.”

“How come you know about the sun-lamp?”

“I had a hunch. I’ve read my P. Zanoski.”

chapter xxxii

The drug in Harry’s system was a liquid clarity.

Was prompting him to level, spill the beans.

“I have a wound.”

“We all have wounds.”

“But mine’s peculiar. Peculiarly mine. It weeps and shines

and sometimes even murmurs.”

“Don’t they all.”

chapter xxxiii

A liquid, improving clarity.

And Rubin was transformed, in Harry’s sight. Transformed

and transfigured. Laundered and sharpened.

The Ray Liotta eyes became apparent; the smile framed by

inverted commas emerged (“v”).

And Rubin unbuttoned Harry’s shirt, gently baring Harry’s

dubious shoulder. And his lips sought Harry’s wound, in

order to kiss it better, in order to seal and heal it with a kiss.

Geoff Cochrane, ‘Little Bits of Harry’ appeared in Sport 32, November 2004 and Best New Zealand Poems 2004.

Selected by Pip Adam: What I love about this work is that it shows Geoff Cochrane at his genre tight-rope-walking best. I met Geoff’s work first in the shape of fiction but I grew to love him in the compression and gap-jumping glory of his poetry. I think Geoff would hate me saying this because his work shows such regard for form – but I feel like genre description pales when we talk about his work. It is like his work creates a new genre – the genre of Cochrane. He is the master craftsman, the Olympic formsman – and he does it all under this cape of laid-back. It takes a lot of work to make something seem so immediate, so off-the-cuff and conversational while weighting it with traditions as old as speech itself.

Pingback: Life : 3AM – Raise the Dawn