Photo courtesy of Hue & Cry Press

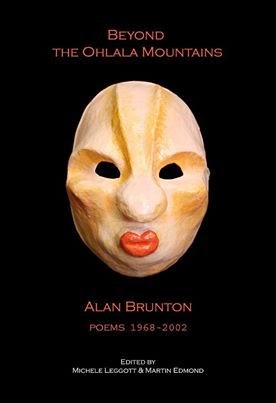

Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle’s debut collection, Autobiography of a Marguerite (Hue & Cry Press, 2014) sent me in search of a new terms to describe the effect it had upon me. This book-length poem is poetry in pieces—poems that piece together an experience of illness, family relations and the need to write. Yet as much as there are threads and mood and revelation, this is lacework poetry. You see enough to experience the whole, and more importantly, to acquire new ways of reading and writing poems.

The book is in three parts and each part works a little differently in terms of writing choices. The first part consists of prose-like poems. The poems in the second part are given more breathing space, but they are interrupted, wonderfully so, by footnotes (and not conventional footnotes, I might add). In the final part, there is a return to poetic prose, or prose-like poetry, that is offset by photographs that take you back to mother and daughter (amongst other things).

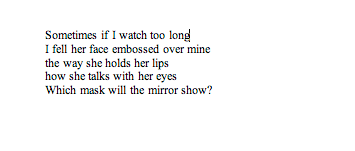

It is a book of illness, anonymous illness, as the details of diagnosis are only ever hinted at. This is poetry of the gap, of the hinted at, and of silence. Names are left off the line. Questions are laid down as statements (no question marks) as though answers are elusive (as indeed they so often are in illness). The silence and the gap suggest that illness is unfathomable at times, hard to tell, exhausting to tell—so much better to divert and filter so it becomes poetic lacework. In the second part, sentences are truncated and left hanging on the line as though the poet is breathless, weary of the full story. To me it is also akin to memory—the way it is spasmodic, episodic, shard-like. If this is lacework, it is a lacework of beginnings. And then life—lifegoes on, uncomfortably, differently with the arrival of illness, as the narrator moves in and out of family and school routines, friendships, her writing.

Each section is full of poetic rewards, but I was particularly taken with the middle section where footnotes interrupt and introduce a different way of reading. Astonishing. These footnotes are taken from books by Marguerite Duras and Marguerite Yourcenar. You physically move your head in and out, up and down—crossing an unexpected bridge between Zarah’s line and the line of a Marguerite (you never know which one). That movement across the bridge is glorious—it produces a tremble and ripple of connections and meaning. This poetry is unlike anything I have seen. I am calling it kinetic poetry. There is the movement across the little footbridges, but there is also the way each discrete line vibrates. Like a little earth tremor. And in these little vibrations, there are miniature collisions between this line and that. Side stepping. Side dancing. Side tracking.

There is so much to love about this book. A thousand movements to take you elsewhere and then return you to the moment, to the page. There is the watch that is often looked at but is not on the wrist—as though illness is a state of not-time, unreal-time, faked-time, thwarted time, longed-for time. Or there is the way the delicious word play takes me to Gertrude Stein (‘poured system’ then ‘Poor system’; ‘weekend’ then ‘weak end of’). It comes back to the way a word stretches to accommodate the nuances and implications of a body ill at ease. Or the way the mother, a Marguerite, flickers and trembles like the narrating I (‘Her mother used to say I don’t know what I’d do without you’ and its footnote ‘You’re right, this is not normal weather for this time of year’). Where does she begin and where does she move to next? Her illness, her illness. Her discomfort, her discomfort. The way words puff out with the need to get things right (‘the filling is not always filling,’ ‘is progress slower than you expected or slower than you hoped’). And the way in illness, and in the memory and physical deposits of illness, writing is vital. An essential anchor. A lifeline.

So much more to write and think which means it is a book of returns.

I just loved this book. Thanks to Hue & Cry Press I have a copy of this book for someone who likes or comments on this post.

Rachel O’Neill has an illuminating interview with Zarah here.

Zarah’s Hue & Cry author page here .