Jillian at the Bluff signpost

Jillian Sullivan has just started walking the South Island section of the Te Araroa trail. I invited her to send poems whenever she felt inspired to do so, internet access permitting.

Friends are why we come home

Friends around the table and all

the glorious food and laughter.

Sometimes I yearned to run away

from here, I told Graeme. But I didn’t

want to leave this. He guessed the weight

of my pack closest, at 14 kilos. Some

said 17. It was 13. Achievable,

then.

The gifts they gave me of their eyes.

The gifts they gave me of their selves,

who know me. And so we said

goodbye. And so it is true

I am going. Margaret took a photo, as pack

on back I walked down the white line

of the empty road running through our village.

A metaphorical photo.

Now it is a thrush singing outside

my window. Bach, Ave Maria,

black coffee. The gentle easing into

leaving this life, for when I come

back, who will I be? Someone

dissolved into trees and rocks and sky?

It’s always Wednesday

It’s always Wednesday, it’s always

eight am, it’s always.

One last morning in the hut, figuring

the right thing to do. What would you do?

Your younger, thoughtful look,

considering. You would tell me to listen.

The final walk along the stream

bearing the heavy pack. The final call in

at Gilchrists Store for the mail. The apples

outside my window growing into their appleness

after such a winter. A sparrow riding high

on the pale green under a grey sky.

The last morning I won’t be hanging onto

every word of the weather forecast.

The last morning casually making coffee

looking around at my books which are

everywhere. Yesterday two more shelves,

already full. The last morning

I will count the weeks to the ten months

you’ve been gone. There is ease in this world

of a physical kind, but then I will learn

how to keep walking. You said it first. Keep on.

While I’m away the sun will take all this

green and lushness and turn it gold, the hay

cut, dried, stacked. A whole season over.

Like another Wednesday.

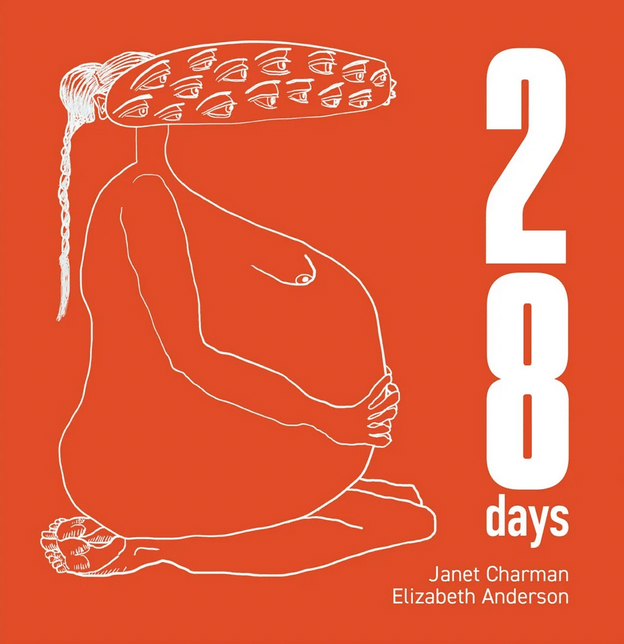

That tramper

Yes, I am now that tramper

who, after the first day

bent under weight in rambunctious

wind, unpacks the pack, examines,

holds, casts away, takes back, casts

away. Gone: rescue remedy,

extra shirt, my darling’s hat, also,

his book of poems. I will have to cleave

them closer. My daughter laughs when I say

I packed a nighty for the huts. Now

I know I am a grandmother. Ok, gone

the nighty, the togs, the jar of magnesium pills,

also, the merino jersey. The wind held me

down and I was hardly a leaf. The photo

at the yellow signpost of Bluff – I’m not

staunch. My legs aren’t even

straight. My body saying,

“You’re going to do what?”

No regrets

The beach is a long wing, of course

you like it; the waves blue, white crests

blown apart by wind, the sand

tawny and firm. But now you have to

walk it as if this is a sentence,

for seven hours, actually, until you turn

from the jauntiness of one step after another,

like hope in the future, which is possibly

why you’re doing this, until about the|

six hour point it all becomes pain.

The thigh bone connected to the|

knee bone, intimately. There is nothing

to be done about the future now, except

keep walking. No-one will save you. Only

the memory at five hours when the young

tattooed builder from Western Australia,

who has caught up to your stride,

stops to swim in the lolloping waves.

You are longing, you are longing to, also.

You won’t regret it, he says. You

take off your clothes on a public beach.

You don’t regret it.

Jillian Sullivan

Oreti Beach

Jillian Sullivan lives and writes in Central Otago, New Zealand. She is published in a wide variety of genres and teaches workshops on creative non-fiction and fiction in New Zealand and America. Once the drummer in a woman’s originals band, and now grandmother of eleven, her passion is natural building. She finished a Masters degree in Creative writing in her 50s, and became builder’s labourer and earth plasterer nearing 60. Now home is the tussock lands, the tor-serrated dry hills and the white flanked mountains of the Ida Valley, where she has 20 acres bordering the Ida Burn, and plenty of room to store clay and sand for future earth projects. Her books include the creative non-fiction book, Map for the Heart – Ida Valley Essays (Otago University Press 2020).