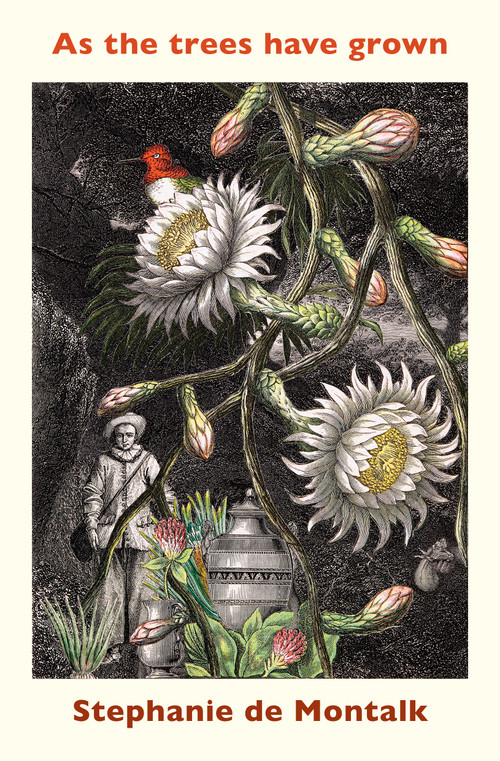

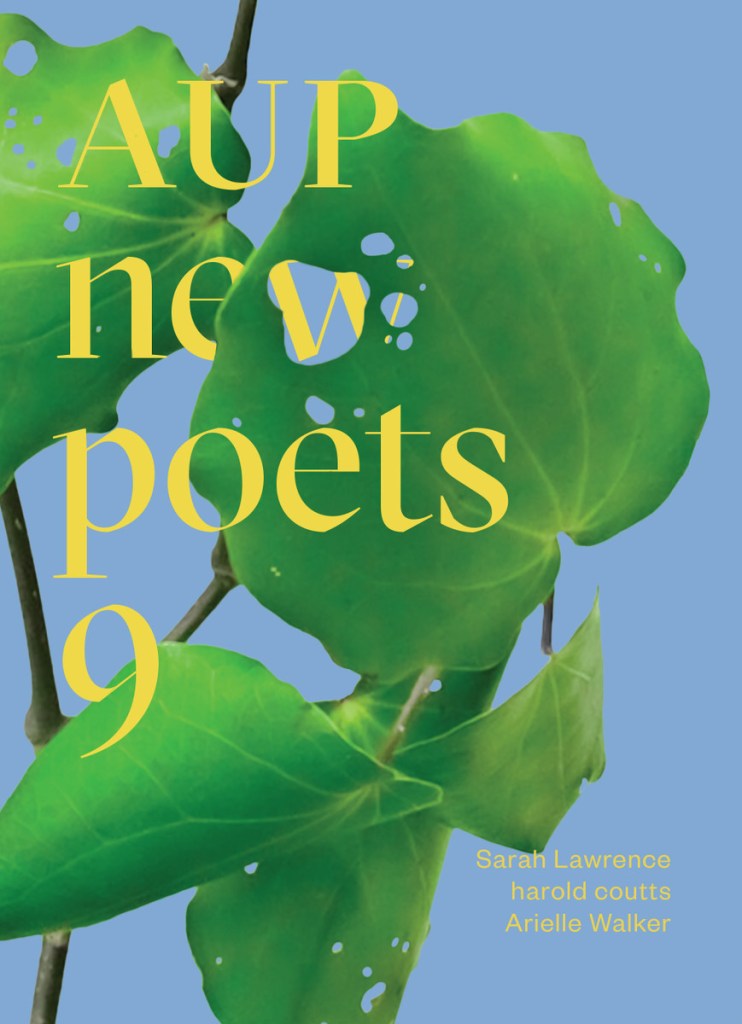

AUP New Poets 9 – Sarah Lawrence, harold coutts, Arielle Walker, ed Anna Jackson

Auckland University Press, 2023

Each poetry book I read this year refreshes the page of what poetry can do. Yet some things remain constant in my addiction to reading poems: musicality, surprise, freshness, movement, heart – in varying blends and eclectic relationships. Aotearoa poetry is doing so much at the moment – there is neither constricting paradigms nor narrow recipes. Instead we get multiple connections along the sparking wires of writing. AUP New Poets 9, edited by poet Anna Jackson, brings sublime new poets to our attention. Anna has edited the series since issue 5 (2019), captivating our attention with the work of poets such as Rebecca Hawkes, Claudia Jardine, Vanessa Crofskey, Ria Masae, Modi Deng. This is Anna’s final issue, with Anne Kennedy taking over the editorial reins for issue 10.

In her introduction, lingusitically agile and idea forward, Anna writes potential pathways and animated openings for the reader. It is the kind of introduction that fertilises a book rather than burying its poetic potential in claustrophobic frameworks.

You can hear harold and Arielle read poems from their sequences here.

Sarah Lawrence

Sarah Lawrence’s sequence of poems embodies all the traits I have listed above. She achieves sweet movement along the line, petal-packed detail, heart spikes, flakes of the everyday alongside shards of strangeness. The combination is electrifying, luminous, immensely satisfying. Musicality is an imperative. Listen to the melody and chords in this stanza:

(…) Stitching the crumbs

into an upside-down cake, I speak slowly

to strangers who blink like cats.

On the lunar eclipse I come home glitter-drenched

to a gaggle of gawkers on beanbags outside, late

for the hole in the sky

from ‘The edge of winter’

I am in awe of the way metaphorical language enhances the physicality of both anecdote and reflection.

(…) The city is beginning

to pepper with faces I know. I can’t

leave our house without seeing at least one

man in a fisherman hat. I can’t leave our

house without saying at least one hello. Yes,

open your orange before we are home, it

is nice to squeeze stories from the rind.

Yes, I am here now & I am no longer

quite anonymous. The city is beginning.

I have never felt so brave.

from ‘real-life origami (to unfold)’

Slender moments shimmer in an intensity that draws love or grief or everyday friendship close. The “you” heightens the intimate layerings, and it is as though we get to inhabit that coveted addressee spot too. We move between the fragile and the tender, resemblance and divergence, the idyllic and the life singed.

Sarah writes with an intimacy ink that gets you warm and heart-touched as much as it startles and surprises. A dazzling arrival.

harold coutts

I find myself saying harold’s poems out loud, delighting in the rhythm and rhyme, the pitch and perfection of sound, and the sequence becomes a poem album on replay. Anna picked out ear-catching rhymes from the sonnet, ‘i am growing a garden’. Listen to that, and then listen to the melodic complexity of this stanza with its ripple lilts:

in the morning i cook eggs to placate the hearth of me

there’s a place for your shoes, still

i have missed you enough to fill all the walls i exist between

but never enough to call you

from ‘cooking eggs for one’

Gender is the insistent blood pulse of the sequence: ‘my gender is my inside room’. Gender is the vital refrain, an issue that links to body presence. The body with skin, lungs, ribcage, a body with growth and bloom, longings and limits. The body that loves and lusts, that eyeballs life or death, that brings itself into mesmerising view through physical detail and metaphor. I am moved immeasurably, held in the grip of heart and bone. The physicality and the animation. Haunted.

i am without my bones

mould me into carpet and lay me down

thus i might get some rest

i saw the sunset and now it rises

mocking the mountains of my eyelids

as i lurch home

from “hi and welcome to ‘i’, tired’ with harold coutts”

There is a sense of the body as threadbare, as shell, as stripped back by rodents. Yet it is also lavender bloom, survival. There are so many essential tracks through harold’s sequence, and I am only offering you this one, this body insistence, because it is gluing me to the lines. The tactile that arrests. The sublime music. Yet you will also fall upon the sun, flowers, swords and knives, swivel chairs, earth and dirt, love, pronouns, heat and sweat, the poet as reader, the reader as writer, and you will simply crave more. This is another dazzling arrival.

Arielle Walker

Reading Arielle’s sequence and I am held close in the tonic of what poems can be. Her opening poem, ‘a poem is a fluid thing all wrapped in fish skin’, is the most tender, the most illuminating embrace of the word and the world – whether physical, relational, heart-strung. Being. Becoming. Becoming poem. For yes, this is an offering of poetry as a form of becoming. I have never thought of a poem as a body of water but it feels so perfect – fluid yes but more than this. Hydrated, generating ebb and flow, life sustaining, beauty delivering.

How can I write a poem unless it rolls (a ready-made

river) out of the side of a mountain and runs gleefully

forward in a rush of eddying currents towards the sea

so that all I have to do is hold out a hand to unravel

the slightest fraying edge of its fluidity, and

spin a new yarn from its depths?

In her bio, Arielle writes: ‘Her practice seeks pathways towards reciprocal belonging through tactile storytelling and ancestral narratives, weaving in the spaces between.’ This resonates so deeply, as the poems are a form of guardianship, of caring for the natural world, trees plants, rivers. I am walking through the poems, hand in hand with a poet guide, making tracks through aural and textured delight, finding awe and nourishment. And as I walk, the guide draws my attention to here and there – I am thinking how caring for the natural world, how standing beside and beholding the sea, how weaving together this story and that story, this heart and that heart, is also a form of reading and writing: we are contemplating, translating, connecting, conversing, imbibing, witnessing, contributing.

Arielle’s form of writing is as full of movement and variation as the sea: constant, same, nuanced. She is spacing out, striking through, bunching up words, using italics, step-laddering. The shifting movement on the line echoes the shifting rhythm that is as visual as it is sonic. The musicality of a view is woven into the image-rich fabric of writing. She is weaving words of multiple languages from Te Reo Māori to English to Shetland dialect. The Scottish heather becomes weed in Taranaki landscapes. The shoormor where sea meets shore in Shetland becomes toes in the water, selkie returning to the sea, the river spine and river mouth, a new form, an old form, a memory, a myth.

she grew accustomed to her new form

learned to exchange salt for soil, built instead

upon the body of a mountain

her brine beginnings buried in the earth

she locked her words away too

dialect smoothed like seaglass

into new vowel shapes

the shoormal, the skröf, the lönabrak

forgotten

from ‘skin’

We will take what we need from the bush and no more. We take what we need from these poems and it will make our heart sing, our feet will plant firmly in the soil as we gather and acknowledge. And it is both essence and wide, irreducible and fortifying. These poems have touched a deep cord. They are quiet and humble and extraordinary in their dazzle.

Three poets with deft and distinctive approaches to writing, three poets who thread preoccupations with acute perceptiveness, earth concerns, personal disquiet and intimate recognitions. This is an anthology to celebrate, to dawdle over and absorb the satisfactions and epiphanies as you read. AUP New Poets 9 underlines the refreshing engagements a new generation of poets is producing in Aotearoa. And yes, altogether dazzling!

Sarah Lawrence (she/her) is a Pōneke-based poet, performer, musician and pizza waitress. She recently dropped out of law school to study acting at Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School. Her parents are thrilled. She won the Story Inc Prize for Poetry in 2021, and you can find her writing in Starling, Landfall, A Fine Line and The Spinoff.

harold coutts is a poet and writer based in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. They have a hoard of unread books and love to play Dungeons & Dragons. Their work can be found across various New Zealand literary journals such as bad apple, Starling, Ōrongohau | Best New Zealand Poems, Poetry New Zealand Yearbook, and in Out Here: An Anthology of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ Writers from Aotearoa edited by Chris Tse and Emma Barnes (Auckland University Press, 2021).

Arielle Walker (Taranaki, Ngāruahine, Ngāpuhi, Pākehā) is a Tāmaki Makaurau-based artist, writer and maker. Her practice seeks pathways towards reciprocal belonging through tactile storytelling and ancestral narratives, weaving in the spaces between. Her work can be found in Stasis Journal, Turbine | Kapohau, Tupuranga Journal, Oscen: Myths and No Other Place to Stand: An Anthology of Climate Change Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand (Auckland University Press, 2022).

Anna Jackson’s latest collection of poetry is Pasture and Flock: New and Selected Poems (Auckland University Press, 2018). She has also released Actions and Travels, a book on poetry (Auckland University Press, 2022). She is based in Wellington.

Auckland University Press page