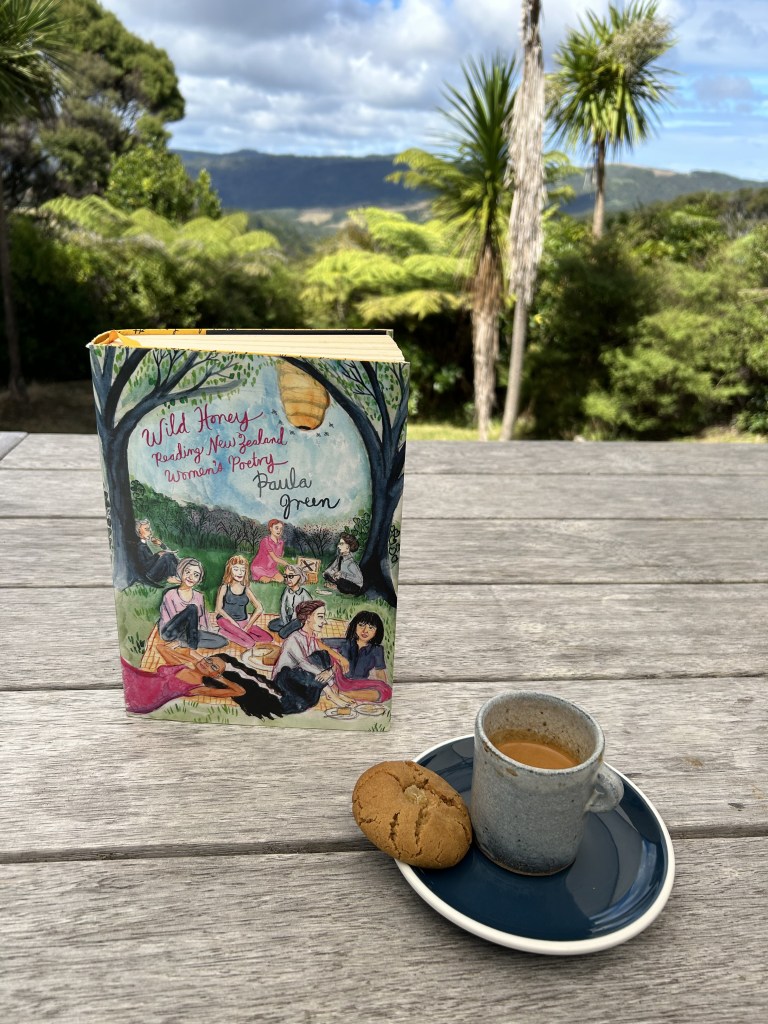

Women have published poetry in Aotearoa for 150 years, but many slipped from public view, were not paid the honour due to them in their lifetimes. Many found it difficult to break the literary hierarchy in order to be published and to write what and how they wanted. In 2019, Massey University Press published my major work, Wild Honey: Reading New Zealand Women’s Poetry. Publisher Nicola Legat welcomed my proposal with open arms and worked tirelessly to help bring the book into the world. I picked up the book today and was immediately returned to the joy of research and discovery, the need to open rather close women’s writing, to assemble a wide range of voices across time, place, age, culture, subject matter and style. Honestly, with my tiny jar of energy stretching to its limits to nourish my blogs and work on my own writing projects, I don’t know how I managed to research and write this book.

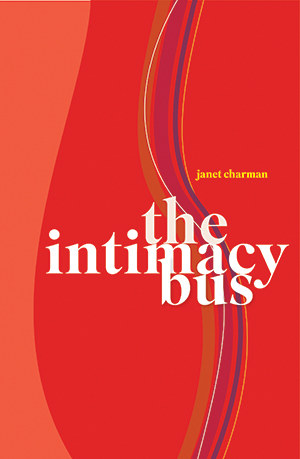

Today I will share a few morsels from it. Sarah Laing did gorgeous artwork for the Wild Honey cover, a group of poets picnicking. On the front: Selina Tusitala Marsh, Alison Wong, Ursula Bethell, Elizabeth Smither, Fleur Adcock, Airini Beautrais, Jessie Mackay, Blanche Baughan and Robin Hyde. On the back: Tusiata Avia, Hinemoana Baker, Michele Leggott, Anna Jackson and Jenny Bornholdt.

The early women, such as Jessie Mackay, Blanche Baughan, Eileen Duggan and Ursula Bethell, paved the way for the poets to come. These women communicated with each other, and with other women interested in literature and politics. A bit like we do today. A bit like the cover of Wild Honey. Today when I review books, I am delighted to read in the acknowledgements pages that women continue to draw strength from other women poets.

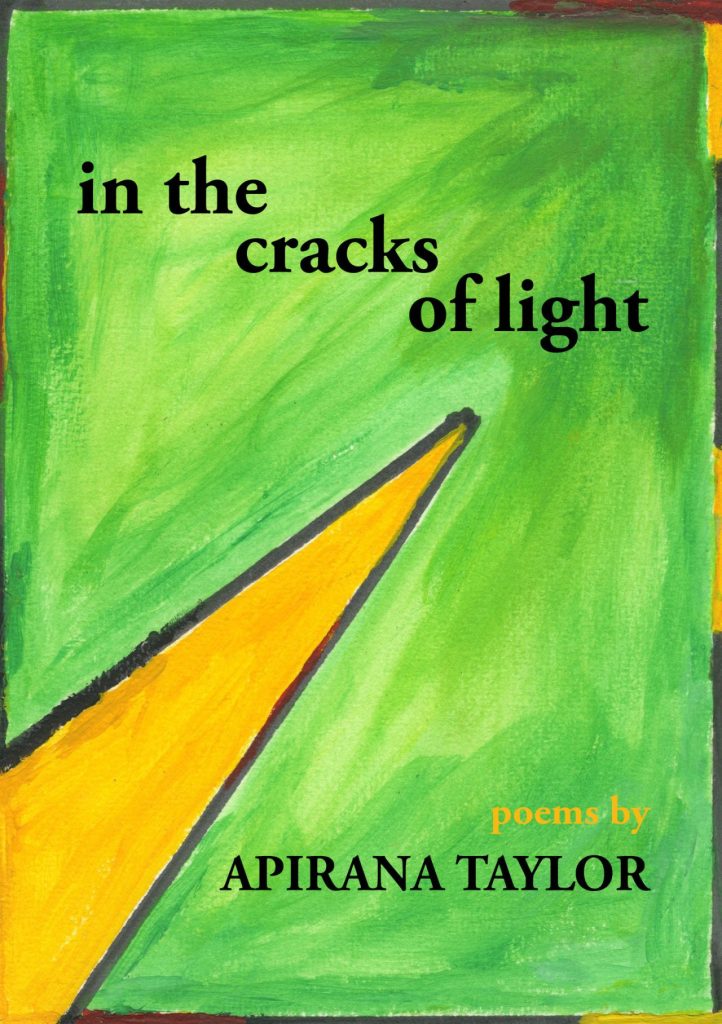

So today on International Women’s Day, I firstly toast four early women poets, and then include a poem from Amy Marguerite’s debut collection, over under fed (Auckland University Press, 2025). It feels perfect to post a poem from this brand new book, this sublime arrival, with its layerings of hungers and intensities, hauntings and recognitions. I will feature Amy and her new book in the coming month or so.

I have three copies of Wild Honey I would like to sign and give away. Leave a comment here or my social media pages if you would like one. Maybe name a poetry collection by a NZ woman poet you have loved.

Jessie Mackay

The Pearl of Women — strong and free;

Great as the coming woman, she.

Deep learn’d and read in student lore;

A mind enlarged to grasp at more.

from ‘The Pearl of Woman’

The Spirit Of Rangatira and Other Ballads

George Robertson, 1889

To enter the ‘feminine’ is to enter a risky label that might limit, stereotype or conversely enrich how we view women. Mackay cannot be pinned to either side: in her writing she is unafraid to represent beauty or challenge beastliness. She unafraid to speak out, and if you consider that feminism is a matter of of making women visible, of giving presence and possibility to women, of expanding options, then Mackay was a feminist.

Blanche Baughan

(…) Hers

Was a keen taste in little things ; she loved

That trivial, intimate, long-drawn-out talk

Of daily happenings, in-and-out details,

And chance of new-old changes, by whose help

Women in villages make shift to weave

Some kind of colour’d arabesque as fringe

To Life’s web, hodden-gray.

from ‘Reuben’

Reuben and Other Poems, Archibald Constable, 1903

I view Baughan’s collections not in the light of a settler-poet inventing a way to forge a poetry-home and failing at every turn, but as a journey to recognise and find peace within her invented and reclaimed self. Her writing cannot be pigeonholed within poetic genres or colonial narratives without losing sight of the woman writing. This is a story partly told. There are many tracks through Baughan’s poems. I have used her skeleton biography to stake a provisional route. Other critics have examined the way Baughan’s poetry grapples with the challenge of writing within the slow and thorny genesis of an emerging New Zealand poetry. The ink in the woman’s pen is not undercut by a lack of vocabulary or pioneering syntax. There are ways we can repack our knapsacks and absorb and feel her poems.

Eileen Duggan

We are the wheat self-sown

Beyond the hem of the paddock,

Banned by wind from the furrows,

Lonely of root and head

from ‘New Zealand Art’,

Poems, NZ Tablet Co, 1921

Duggan wrote as a way of anchoring and liberating the physical and spiritual contours of home, and that home was resolutely New Zealand. Her poetry embodied New Zealand. Just as New Zealand was a form of poetry for her. Yet for decades Duggan’s poetic choices rendered her version of home mute. She is our pioneering songbird.

Ursula Bethell

But then these stinging sun-roused messages

tossed hither salt-cold from the pacific sea;

those foremost, dawn-dyed, rose-red eminences,

those snow-fast, soon-to-be-incarnadined strongholds beyond …..

from ‘July 9. 1932. & A.M.’

Collected Poems, Caxton Press, 1950

The more I read Bethell’s poetry and letters, the more I move beyond her characteristic reserve, the more I feel that this is a woman to whom I could devote an entire book. She is a knotty mix of reticence, acute intellect, acerbic advice, crippling heartbreak and poetic dexterity. Bethell rightly countered M. A. Inne’s claim in her 1936 Press review of Time and Place that ‘the poet knows no school mistress but her garden’ with the point that ‘the garden was a brief episode in a life otherwise spent’.

Amy Marguerite

home to you

cate le bon wrote a song called

what i called this poem it’s

4.13 i want a beer and paul’s

celebrating his graduation

at the bar i’m invited and that’s

so nice. it’s usually a bad sign

when i just want to drink

alone. it wasn’t usually bad

until claudia i got so ill then

better again when she went

to england and stayed there.

a week before i moved to melbourne

i told helen that i had fallen

in love. she said that’s usually

what happens and i nodded

at the screen like it had

happened before. it’s maybe

like finally writing the poem

for the first time like finally

telling that difference to matter.

tonight i’ll put on james salter’s

reading of ‘break it down’

wait as i usually do for the old shirt.

i don’t dread the endings of

things i’m going to have to

leave that somehow unlearn

autumn and get a job. but

my desire is not entirely over

in this place i’m still unleashing

pathetic furniture stopgaps for

when the beer fails and it does that

a lot up half the night without you.

i think so many stories are

flights we forget to run for

bridges we can’t drape across

the feeling only ever properly

borrowed if i never give

it back. i’m sick of the torch on

everything. that’s always

not mine. hung up on all that

true pretending like an unrequited

apparition old shirt without

ever actually calling it old and

there’s the usual design. i’m

not incapable of it just unfit

to adequately adore it compromise

the corporeal sconce how it

makes me real. are you as well

drinking alone with ungood thoughts.

reimagining that home to.

that home

too.

Amy Marguerite

from over under fed, Auckland University Press, 2025

Amy Marguerite is a poet and essayist based in Tāmaki Makaurau. She completed an MA with distinction in creative writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters in 2022. Her poetry has appeared in anthologies including Spoiled Fruit and white-hot heart and has featured in literary journals, magazines and publications including Starling, Turbine and Sweet Mammalian. Her essay on the new generation of Aotearoa poets appears in Auckland University Press’s forthcoming anthology Te Whāriki.

Blanche E. Baughan (1870-1958) was born in Surrey England. She graduated from the University of London and was its first student to gain a BA (Hons) in Classics. A poet, nonfiction writer, social worker, prison reformer and suffragette she was initially published in England. She travelled to New Zealand in 1900, eventually settling on the Banks Peninsula in Canterbury. Blanche published several poetry collections, along with books of prose pieces (Brown Bread from a Colonial Oven, 1912), travel writing (Studies in New Zealand Scenery, 1916) and articles on prison (People in Prison, 1936). In 1935 she was awarded the King George V Jubilee medal for her services to social work. Damien Love edited a selection of her writing in 2015.

Ursula (Mary) Bethell (1874-1945) was born in England, raised in New Zealand, educated in England and moved back to Christchurch in the 1920s. Bethell published three poetry collections in her lifetime (From a Garden in the Antipodes, 1929; Time and Place, 1936; Day and Night, 1939). She did not begin writing until she was fifty, and was part of Christchurch’s active art and literary scene in the 1930s. A Collected Poems appeared posthumously (1950). Her productive decade of writing was at Rise Cottage in the Cashmere Hills, but after the death of her companion, Effie Pollen, she wrote very little. Vincent O’Sullivan edited a collection of her poetry in 1977 (1985).

Eileen Duggan (1894-1972) of Irish ancestry was born in Marlborough, and grew up in Tuamarina, near Blenheim. Duggan graduated from Victoria University with an MA First Class Honours in History (1918). She briefly taught as a secondary school teacher, and as an assistant lecturer before devoting herself to writing full time. She wrote essays, reviews, articles, a weekly column for the New Zealand Tablet (from 1927) and published five collections of poetry. Three collections were also published in the United States and Britain to international acclaim. She left a substantial body of unpublished material which Peter Whiteford drew upon for Eileen Duggan: Selected Poems (1994). She was awarded an OBE (1937) and was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (1943). She lived most of her adult life, with her sister, in Wellington.

Jessie Mackay (1864-1938) was born in the Rakaia Gorge, Canterbury, to Scottish parents. After training as a teacher at Christchurch Normal School, she taught at Kakahu Bush School (1887-1890) and Ashwick Flat School (1893-1894). She then worked as a journalist, writing a fortnightly column for the Otago Witness from 1898 and then as Lady Editor at the Canterbury Times, and as a freelance writer. She was an active member of the National Council of Women and strongly supported the suffragette movement. She published six collections of poetry. In 1936 Mackay was granted a life pension of £100 for her contribution to New Zealand letters, and in the year of her death, PEN organised the Jessie Mackay Memorial Prize for verse.