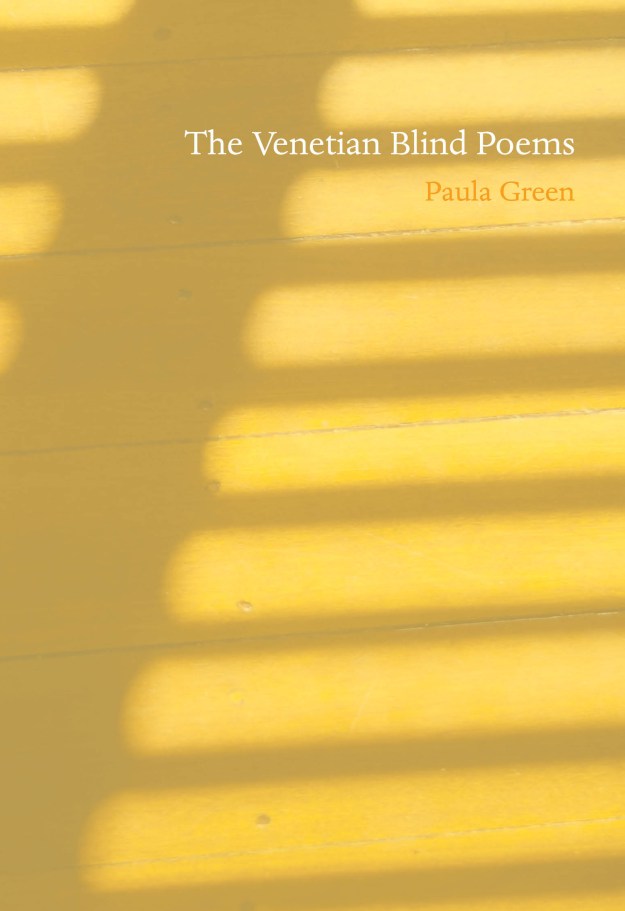

The Venetian Blind Poems, Paula Green

The Cuba Press, 2025

Later in the year I am planning a number of Poetry Shelf live events to celebrate poetry voices in Aotearoa. This month I have a new poetry collection out but my energy jar and immunity is not quite ready for book launches so I have invented three celebrations for the blog. On Publication Day (August 1st), I posted an email conversation I had with my dear friend Anna Jackson, a conversation that celebrates our shared love of writing and our two new books. Anna’s Terrier, Worrier (Auckland University Press) and my The Venetian Blind Poems (The Cuba Press).

For my second feature, I have created a collage conversation by inviting some of the poets whose books I have reviewed and loved over the past year to ask me a few questions. It gives me another chance to shine light on the extraordinary writing our poets are producing. I have kept the conversation overlaps as I find something new when I return to a similar idea or issue.

It is with grateful thanks to David Gregory, Mikaela Nyman, Cadence Chung, J. A. Vili, Rachel O’Neill, Kate Camp, Xiaole Zhan, Claire Beynon and Dinah Hawken, I offer this conversation in celebration of poetry. You can find links to the reviews below. The conversation has ended up being something rather special for me. I have never experienced anything quite like it! I loved the questions so much. Thank you. Because this is a book of love, I would like to gift signed copies to five readers, whether for themselves or a friend (paulajoygreen@gmail.com).

I also want to share a review Eileen Merriman posted on her blog after reading my book, because she is in the unique position to respond to it as another writer, a haematologist and a close friend. Some things she says struck me and I refer to them when I answer a question by Kate Camp.

I’ve just finished reading Paula Green’s recently published poetry collection, The Venetian Blind Poems in one sitting. This book was an oasis in the midst of a hectic time for me (when is life ever not?); it’s not very often I can be compelled to sit for more than half an hour currently. Yet I connected with this on so many levels: as a writer, as a doctor, as a patient, as a friend, as a human. Green details her experience on the Motutapu ward, the bone marrow transplant/haematology unit at Auckland Hospital, where she received a bone marrow transplant for a life threatening blood disorder in June 2022.

As a haematologist, I know this is one of the most challenging treatments you can put a patient through, bringing someone to the brink of death to save a life. Recovery takes months, sometimes years. The acute phase can be akin to torture, one only the recipient could ever understand. But Paula holds us close, so that we can begin to understand: ‘I return to the pain box in Dune… I am using the box/for when my ulcerated mouth pain is unbearable/last night I held the box/as the mouth pain radiated but/I didn’t put my hand in/I decorated the box/ with seashells instead’. And then we are elevated from the abyss to the sublime, because this is how Green survives, by stacking poems along her windowsill and creating word pictures in her head: ‘Buttered toast and clover honey/marmalade brain and mandarin heart’. And then, time and time again, we are brought back to the world that Green sees, from the confines of her isolation room, peering through the Venetian blinds at the world that sustains her, one second, one minute, one day at a time.

This book had me captivated from the delicious first line ‘Liquorice strips of harbour’, throughout the rough seas, eddies, near-drownings and becalmed harbours of the stem cell transplant, and beyond, right through to that hopeful last line, ‘We will be able to see for miles’. Kia kaha, Paula Green, your inner strength knows no bounds.

Eileen Merriman

me with my daughter’s dog, Pablo

a collage conversation

Every morning I open an envelope and

read a poet’s choice inside a greeting card

I nestle into the joy

of Cilla McQueen’s kitchen table

David Gregory

David: Where do your ideas for your poetry come from?

Paula: They fall into my head like surprise word showers, whether from what I see, hear, feel or read. From the world experienced, the world imagined, the world recalled.

David: How do you know when a poem is complete?

Paula: It’s a gut feeling. When it hits the right notes and catches a version of what I want to transmit. Poetry can be and do so many things, and I’m a strong advocate for poetry openness rather than limiting and conservative ideas on what a poem ought to be. Paul Stewart from The Cuba Press edited the book and he has a sublime ear for poetry and its range. You couldn’t ask for a better poetry editor.

In the middle of the night

the radio takes me to Science

in Action and I am listing

ways to save the planet

and the way dance liberates

cumbersome feet

Mikaela Nyman

Mikaela Nyman: These poems emerged out of a life temporarily reduced by severe illness. Yet they’re not limited by the medical circumstances, and not merely a comfort blanket, but seek to connect with the world outside. Did this happen straight away, or is it something you consciously pursued later in the writing process?

Paula: I love this question – yes my life was limited physically, not only on the ward but on my long recovery road with a fragile immune system, daily challenges and minute energy jar. But I also saw it as an expansion of life. I focused and am focusing on what I can do, not what I can’t do. On the ward, the world was slipping in through the blinds as much as I was looking out. From the start my writing navigated both my health experience and the world beyond it.

Mikaela: Given the dire circumstances that compelled you to turn to poetry at this point in life – i.e. your personal health struggle as well as the state of the world – how important is it for you to retain hope and offer a sense of wonder in your poems?

Paula: I think it ‘s been ongoing, across decades, my impulse to write through dark and light. I think all my books have sources, whether overt or concealed, in patches of difficulty. I was writing 99 Ways into NZ Poetry with Harry Ricketts when I was first diagnosed and I never stopped writing. Maybe writing is my daily dose of vitamins. And that word wonder. Wonder is a talisman word – whether it’s the delight you might find in thought coupled with the delight you might find in awe. It is a crucial aid.

It’s the third day of the poetry season

Oh, everyone’s queueing up to read

a poem and count falling leaves

Cadence Chung

Cadence: Do you have a particular line/poem you’ve written that you think really encapsulates the collection?

I will meet you at the top of the hill

we will be able to see for miles

Cadence: What’s an experience you’ve had lately that has brought you joy?

Paula: Ah, such an important question. Every day is a patchwork quilt of joy. Take this day for example. Reading and reviewing a poetry book. Drinking coffee with a homemade muffin with sun-dried tomatoes and paprika. Making nourishing soup for lunch and sourdough with millet flour for a change. Watching the pīwakawaka dance in front of the wide kitchen window as though they are rehearsing for an special occasion. Replying to children who have sent me poems for Poetry Box. Cooking a Moroccan tagine with preserved pears and rose harissa paste for dinner and sharing with my family. Listening to Jimmy Cliff on repeat all day and imbibing the uplifting reggae beat and need to protest.

This morning I got up at 5 am to drive to an early appointment as the full-wow-moon shone in the dark, and streaks of bright colour ribbons hung over Rangitoto. It felt like my heart was bursting. I switched to Maria Callas singing ‘Casta Diva’ from Bellini’s Norma.

Today I feel happiness

as solid as a wooden

kitchen table with six chairs

and a bowl of ripe fruit

Cadence: How does a poem come to you? Quickly and all at once, or more measured and worked out?

Paula: Poems linger in my head -as they did on the ward – before I write them in a notebook. Often poem fragments arrive in the middle of the night, or when I am driving across country roads to Kumeū. But there is always a sense of flow not struggle. I love that.

I decide even stories are slatted

with missing bits, so I lie still and

fill in the gaps of my childhood

J. A. Vili

Jonah: How did your writing flow in the light and dark times, on the good

days and bad days of your recovery journey?

Paula: It flowed and flows in my head, most days, slowly, slowly. But sometimes, especially in the dark patches, I don’t have the energy to write on paper. I can’t function. Words falter. I compare it to the stream in the valley – sometimes it flows like honey, sometimes it struggles over rocks and debris. When it’s honey flow I write, when it’s not, I do something else. So I pull vegetables from the fridge of garden and make a nourishing meal to share with my loved ones. Or watch Tipping Point on TVNZ! Or listen to an audio book.

Jonah: How much did writing these poems during your personal struggle help in

your healing and recovery?

Paula: To a huge degree. And it still does. It was and is a crucial aid because it was and is a way of connecting with the world and people, of feeling love though my love of words. It’s a vital part of my self-care toolkit.

Jonah: Since this was such a personal journey for you, what was something new you discovered about yourself and life itself?

Paula: How in the toughest experience you can feel humanity at its best – for me the incredible care and patience of the doctors and nurses, no matter how tired or stretched they were (and underpaid). I loved my time on the ward. An anonymous donor gifted me life and that felt extraordinary to me. This miracle gift – it felt like I was seeing and experiencing the whole world for the first time and it was a wondrous thing. And still is (despite the heart slamming choices of certain leaders and Governments). It’s recognising what is important. Cooking and sharing nourishing food (especially Middle Eastern flavours). Watching football. Listening to music on repeat: reggae, Bach, opera, Reb Fountain, Boy Genius, Nadia Reid, The National, Marlon Williams, Lucinda Williams, Billy Bragg, Delgirl, Nina Simone,more reggae. I am hooked on Jimmy Cliff at the moment and the struggle he was singing about way back in the 1960s and 1970s: our half starved world, the Vietnam War, the broken planet, the ‘suffering in the land’. Well we are still singing and writing these same songs of heartbreak and protest.

In the basement of song

there are jars of pickled zucchini

worn shoes and well-thumbed novels

Rachel O’Neill

Rachel: Where does a poem generally begin for you, and has that changed at any point?

Paula: In my conversation with Anna, I talked about the way phrases drift into my head, surprise arrivals in my mental poetry room. I referred to these arrivals as gentle word showers. I have had these arrivals since I was a child. when I was in Year 8 (Form 2) my teacher, Frederick C. Parmee, was a poet! He was the only teacher who saw the potential in me as a writer and I flourished. By secondary school I was shut down as wayward and I failed school. Yet the words kept falling into my mind, and then into secret notebooks (like many women across the centuries), across my years of travelling, living in London, and finding a place in the Italian Department at the University of Auckland. Taking an MA poetry paper with Michele Leggott. Getting a poetry collection published with Auckland University Press. Extraordinary. And still the words drift and fall.

Rachel: Does your new collection speak to dynamics of patience and urgency? Along these lines, what has writing this collection made you appreciate more, or challenged you to move on from?

Paula: I think it has amplified my attraction to slowness, to patience, to writing and reading and blogging like a snail, into uncharted territory as much as into the familiar. When you run on slow dose energy, I think urgency is disastrous – I favour slow cooked braises and sourdough bread. Choosing the slow reading of poetry books, so much more is revealed. Yet urgency is both rewarding and necessary for other people, and produces breathtaking results, it just doesn’t work for me. That said, we need to unite with urgency to heal this damaged planet.

The second part of your question is crucial. In a nutshell, I appreciate life, I have had a transplant that has gifted me the miracle of life. Extraordinary. How can this not change the way I am in the world. What matters. Dr Clinton Lewis at Auckland Hospital has made an excellent video for bone marrow transplant patients. He talks about how many patients reassess what matters most. I have drafted a book, A Book of Care, it is not quite ready yet, but it is the manuscript I am most keen to be published. I offer it is as a self-travel guide, a tool kit, borrowing practical ideas that have helped me.

Rachel: In what ways do you think poetry helps us integrate and accept tension or discomfort as part of human experience and living a full life?

Paula: I love this question. I have been musing no matter what I am writing, the tough edges of the world, the daily wound of news bulletins find their way in. What difference does it make if we speak of Gaza and the abominable choices our Government is making? I just don’t know, but I do know silence is a form of consent, and that in the time of fascism in Italy, it was strengthening that some people spoke out. Every voice ringing out across the globe, in song or poem or article, every protest march and banner, is a human arm held out, a call to heal rather than destroy, to feed rather starve, to teach and guide the whole child rather than discriminatory parts.

My repugnance

at the devastation of Gaza

is not eased by the soft light

on the Waitākere Ranges

or a canny arrangement of summer nouns

or Boy Genius on the turntable

or even a bowl of chickpea tajine

Kate Camp

Kate: do you ever feel when you are writing about personal experiences – especially intimate ones of the body – that you are invading your own privacy? And once you have written about those experiences, do you find that the poem version overlays the “real” remembered version? Or if not overlays it, then how do they co-exist, how does the personal, private version of the experience alongside the version of the experience as captured in a poem?

Paula: I love love this question Kate. Xiaole introduces their reading for a Poetry Shelf feature I am posting on Poetry Day, by talking about oversharing. I know this feeling so well. I feel like I am doing it in this collage conversation! To what extent do people want to hear about illness? About bumps in the road? I started sharing my health situation on the blog because I wanted people to know why I was operating on a tiny energy jar and couldn’t review quite so many books or answer emails so promptly. And most people have been unbelievably kind. I felt so bad when I hadn’t celebrated a book I had loved. And then I would think EEK! And wanted to delete my talk of cancer and transplant experiences and issues. But what I don’t do is go into dark detail. That stays private and personal. Will I have the courage to press ‘publish’ for this collage conversation! Scary.

I found it so illuminating to read Eileen’s review of the book. She writes from her experience as a writer, avid reader, haematologist and my friend. She says things I don’t have running through my head but are important! To read her words made feel so much better about how I am handling my recovery road and my own writing! I don’t use warrior language on my cancer road. I don’t wallow in what I can’t do. I have never said ‘why me?’. But I do have dark patches where I feel I physically can’t function. To hear doctors say a bone marrow transplant is an extremely tough experience is like getting a warm embrace. Recognition.

So yes, I love the idea of a private version and a shared public version – I am a writer that keeps most of my life private – my personal relationships, especially with my partner and our children. I think part of my impulse to write this experience was self-care, as I mentioned to Jonah. Liking drinking water. And how important it is for me to write out of aroha and wonder as much as difficulty. To write as you travel, in the present tense of experience. Once I had spent two years writing the sequence, I wanted to get to get the book published as a gift for doctors, nurses and other people ascending Mountains of Difficulty.

After a night of dream scavenging

I open my mouth

and out fly stars

a garden of leeks and carrots

a family of skylarks

a track to the wild ocean

Xiaole Zhan

Xiaole: I’ve been thinking a lot about this idea from e.e. cummings: ‘To know is to possess, & any fact is possessed by everyone who knows it, whereas those who feel the truth are possessed, not possessors.’ Did you have any experiences of not knowing or of ‘being possessed’ while working on/ living through your collection?

Paula: What fascinating traffic between knowing and feeling! Possessing the facts, being possessed. What slippery territory . . . truth yes, but even facts. Are they ever fixed or certain? Sometimes I think writing is a way of re-viewing an experience, of re-speaking it say, and it is for me an organic process. Never fixed. The versions I tell my consultant, the nurse, my psychologist, my close friends, my family, are tremble stories, never fixed, as I remember and forget and shift the focal lens, the distance finder, the colour filter. It is so very important. I almost feel like venturing to Zenlike thought by saying there is knowing in the unknowing, and unknowing in the knowing.

I lip read the cloud stories

and remember the comfort points

Claire Beynon

Claire: I appreciated the absence of ‘explicit’ punctuation in your collection—all commas, colons, semi-colons, full stops are invisible/implicit. The rhythm and cadence of each word, line and stanza work quietly and diligently on their own, as if seeking connection and continuity. They neither ask for, nor require, anything extra in the way of emphasis or embellishment. Did you set out to write the collection this way? Or did you initially include ‘traditional’ punctuation and make a decision to remove it later/during your editing process?

Paula: Punctuation is an aid for the poem – for me it is a key part of the musical effect – and it is a guide for the reader – where to take a breath or to pause. I have had many books published and worked with many editors and they have different, and at times, contradictory approaches. I wanted to keep faith with the first section of The Venetian Blind Poems as I gathered it in my head on the ward. Punctuation played more of a role in the second section which I wrote back home. A musical tool. A rhythm aid.

Claire: I wondered while reading The Venetian Blind Poems whether living with a painter—your partner, Michael Hight—influences your way of composing and structuring your poems? I mentioned in my FB post that something about the tone and shape of this collection reminds me of the work of artist Giorgio Morandi. I’ve long admired Michael’s paintings, too—their quiet, contemplative quality, compositional sophistication and attention to detail, the at-times unexpected juxtaposition of objects—and sense between them and your poems a kind of reciprocity or shared sensibility.

Forgive me if I’m projecting here. I don’t mean to speak out of line or to make any assumptions… but, well, I found myself wondering about these things… how there seems to be something deeply simpatico between your work and Michael’s. And it moves me/strikes me as beautiful.

Paula: Michael and I are big fans of Morandi! We live very separate creative lives – he doesn’t enter the poetry room in my head and I very rarely walk up the hill to his studio – neither of us talk about work in process with anyone. But I have written about Michael’s work (read a review of his last Auckland show here). We have his art on our walls and it’s uplifting, a vital form of travel. I give him my manuscripts to read just before they go to a publisher! We have two creative daughters and we have shared love of books, movies, music and art. To be in New York together absorbing art, music, literature and food was incredibly special – and Ireland, Barcelona and Lisbon on another occasion – and of course Aotearoa.

Claire: I realised when I reached the last page of your collection that I’d read the book as one long poem—a whole comprised of many parts, yes, but essentially ‘one poem’. I actively appreciated the fact that, aside from the titles at the start of each of the two sections, there are no titles to distract or interrupt the flow of the writing. This allows readers to fall into step with you and walk more closely alongside. On the last page, you seem to confirm this:

Most of this poem

is in 1000 pieces

in a box on the table

Do you see the collection as one poem?

Paula: Yes I do! One poem like a quilt made of many notes, light and dark patches.

A poem might be an envelope

to store things in for a later date:

old train tickets postcards buttons

a map of Rome a bookmark

Dinah Hawken

Dinah: A few weeks ago I found myself asking myself what I most hoped my poems would do now that I’m in the last part of my writing life. My main hope is that a few readers will feel ‘be-friended’ by a poem of mine, in the way I have felt be-friended by the poems of others. Then, in reading your conversation with Anna (Jackson), I came across – with surprise – your idea of ‘poetry as friendship’ and Anna’s of poetry as ‘a short cut to intimacy.’ Do you have more to say about this?

Paula: Anna and I have been friends since my first collection Cookhouse was published in 1997, when I had just completed my Doctorate in Italian. Before our slow-paced email conversation, I had never thought of poetry as friendship, but the more I thought of it, the more it resonated as an idea and a practice. I realised my slow-tempo approach to poetry – to reading, writing, blogging and reviewing – is a way for forging connections, of holding things to the light to see from different angles, explore multiple points of view, experiences, hues and chords. Of listening. Our poetry communities in Aotearoa are so active and so strengthening. As this collage conversation underlines.

Dinah: And were you thinking of a particular kind of reader (say someone who had experienced serious illness) when you were writing The Venetian Blind Poems?

Paula: No, I wasn’t thinking of a reader at all. Of getting published. I write first out of my love of writing, as a form of nourishment, as a source of joy. So I guess that is selfishly writing for one’s self. Inhabiting the moment. But now that The Venetian Blinds Poems is out in the world, to be able to give copies to doctors, nurses and other people going through difficult health experiences matters so very much. And to other poets! Climbing a mountain can be hard but it can also be a source of beauty, and I am nothing, this book is nothing, without my support crew, particularly Anna Jackson, Harriet Allan, Eileen Merriman, Michele Leggott and all the fabulous doctors and nurses on Motutapu and the Day Stay Ward. All the readers and poets who contribute to Poetry Shelf as both readers and writers. And my dear family. Thank you. My dedication catches how I felt when I had finished writing the book:

for everyone

ascending the Mountains of Difficulty

and their support crews

David Gregory, Based on a True Story, Sudden Valley Press, 2024, review

Mikaela Nyman, The Anatomy of Sand, THWUP, 2025, review

Cadence Chung, Mad Diva, Otago University Press, 2025, my review

J. A. Vili, AUP New Poets 11: Xiaole Zhan, Margo Montes de Oca, J. A. Vili

editor Anne Kennedy, Auckland University Press, 2025, review

Rachel O’Neill, Symphony of Queer Errands, Tender Press, 2025, review

Kate Camp, Makeshift Seasons, THWUP, 2025, review

Xiaole Zhan, AUP New Poets 11: Xiaole Zhan, Margo Montes de Oca, J. A. Vili

editor Anne Kennedy, Auckland University Press, 2025, review

Claire Beynon, For when words fail us: a small book of changes,The Cuba Press, 2024, review

Dinah Hawken, Faces and Flowers Poems to Patricia France, THWUP, 2024, review

The Cuba Press page

Paula Green and Anna Jackson in conversation

Am looking forward to reading deeply your book. My copy sits, the colour of marmalade, waiting for the right time for me to take it all in. Kia kaha, Paula.

LikeLike

Pingback: Poetry Shelf celebrates The Venetian Blind Poems: a gathering of illness poems | NZ Poetry Shelf