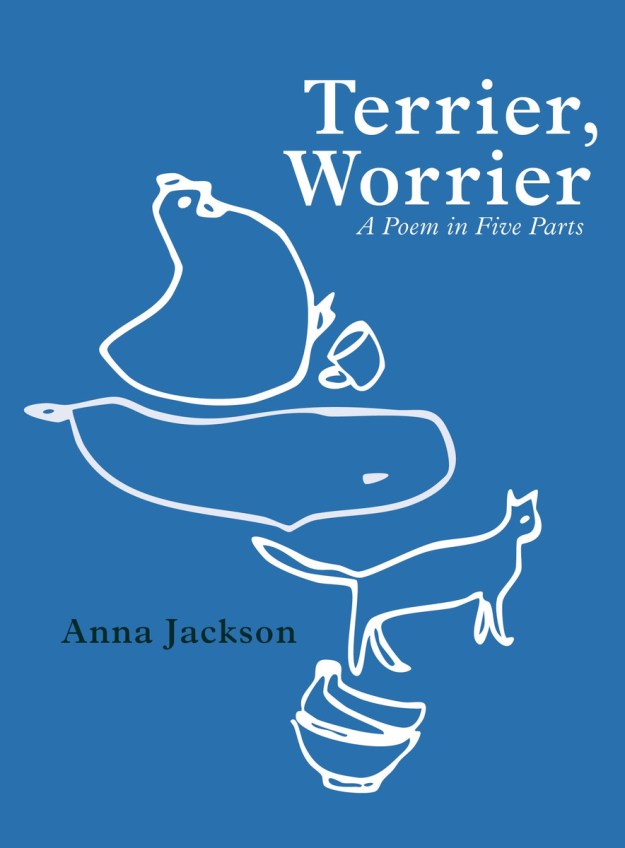

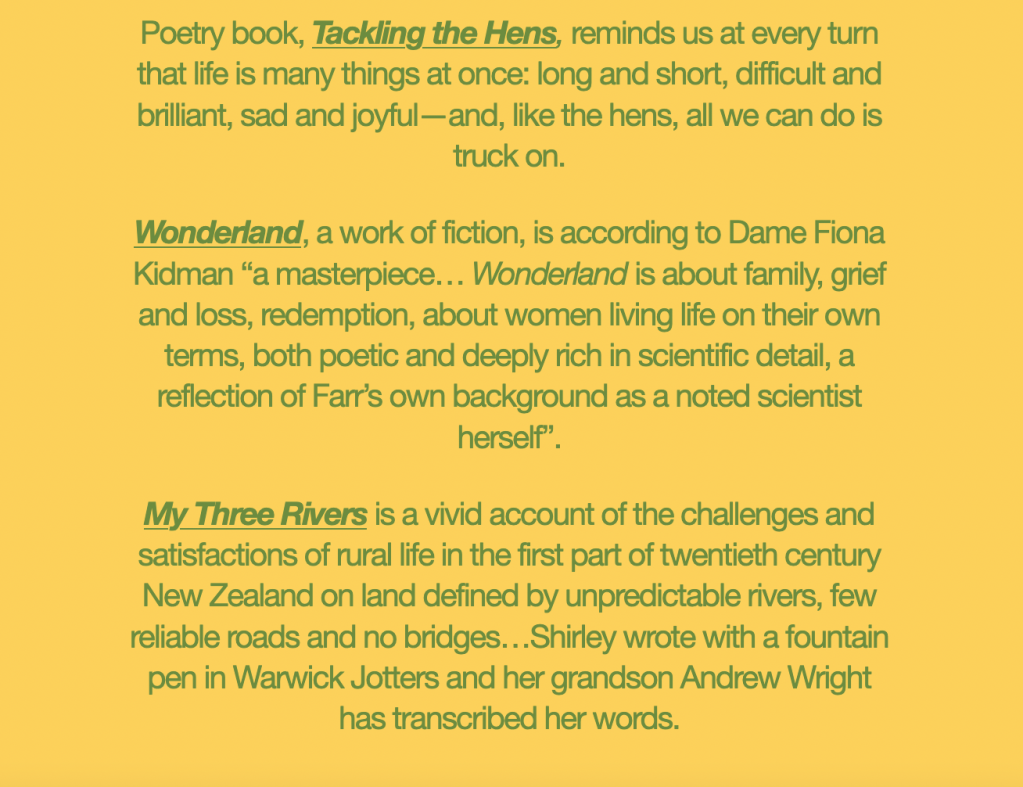

Terrier, Worrier A Poem in Five Parts, Anna Jackson

Auckland University Press, 2025

“She came upstairs looking more like a cloud than a silver lining.”

Loop: A Review in Nine Parts

LOOP

Anna Jackson’s glorious new collection, Terrier, Worrier A Poem in Five Parts, gets sunlight slipping through the loops of my thinking, reading, dreaming. The collection is offered as a seasonal loop as we move through summer, autumn, winter, spring, summer, and in this temporal movement, the loop regenerates, absorbing and delivering rhythms of living . . . mind and body . . . rhythms of writing . . . nouns, verbs, conjunctions . . . rhythms of thinking . . . and little by little . . . the compounding ideas, the feelings. It’s poetry as looptrack: overloop, underloop, throughloop.

I photographed a floor softly tiled in white and grey and

posted it with a quote from Emily Brontë’s diary: ‘Aunt has

come into the kitchen just now and said, “Where are your

feet Anne?” Anne answered, “On the floor Aunt.”‘

BREAKING THE FRAME

There is a long tradition of breaking the frame of poetry, or let’s say opening the frame, widening, nurturing, reinventing, rebooting, invigorating. And yes, there is sunlight drifting in through the gaps in these poetry weatherboards, lighting up what poems can do or be, both beyond the frame and within the frame. Subject, style, sensation. Anna writes:

Poetry can be a form of refusal as well as openness.

I am reading this poetry book at the kitchen table and it is a loop of ignition points. Anna also writes:

I thought, it tells us something about poetry that when we

need to talk to ourselves about something we don’t know

we know, we tell it to ourselves when we are sleep, in images

we struggle to remember when we awake, and often take

more than one reading to fully understand.

PRESENT TENSE

There’s a long black cloud streaking from the west coast to the backyard bush sprinkling salt and pepper rain. Terrier, Worrier is generally written in the past tense, with many stanzas beginning with ‘I thought’, yet for me, curiously, wonderfully, it carries the charismatic freight of the present tense, the sweet fluidity of the gerund, the present participle . . . where be-here-now fluency prevails regardless of gaps, rest-stops, hesitancy. Reading is to be embedded in the moment of the past as reader, so that what happened, and what was thought, becomes acutely present. Dive into the poetry currents in the collection, and along with the writer, you will might find yourself filtering, evaluating, experiencing, valuing, photographing, documenting, thinking. Savouring a moment.

I remember sitting in the car after work, not wanting to turn on the windscreen wipers because I felt like I needed rain on the windscreen to do the work of crying for me.

THOUGHT

Thinking. Yes Terrier Worrier is a poetic record of thought that offers anchors, the cerebral terrain of the philosopher say, an archaeology of ideas to dig for. Where testing the possibilities of what is matters along with what is not, along with everything in between. Poetry forms a thinking loop, a porous border between poem and idea, where meaning is organic, fertilised by nuance and shifting light. Sunlight say. Looping motifs and coiling thinking, like the surprise delight of letting thoughts carry you without planned itinerary. Where meaning ripples and slides. This is what happens as I read Terrier, Worrier.

Anna writes:

I thought, most of the time I, too, am a person not having thoughts but only having sensations, emotions, instincts, memories, anticipations.

Perhaps the poem becomes the vessel for ‘sensations, emotions, instincts, memories, anticipations’.

PRESENCE

Anna’s poetic record of thought (how ‘record’ resonates with the effects of tracks and music) is physically active. Thinking is anchored in a physical world, a yard of hens, a cat, partner, mother, father, daughter, son, friends. A tangible texture of dailiness that grounds the rhythm of thought in physicality. I love this.

Beside my bed there is a painting of a blue fish, floating high above a grey-blue sea, impaled on a grey-blue spike. On the back of the painting are written the words of the artist, my daughter, aged 3: ‘This is the fish. I painted it because it stuck in my mind.’

DREAMING

Dreaming becomes thinking becomes inventing becomes dreaming. Anna holds the idea of dreaming, like a prism on her palm, to question, revisit. Again I’m acutely aware how everything I have already said feeds into what I am saying here, and what I will say. How dreaming is the present tense, looping past and future, how the poet wonders her dream, with dream seeping into life and life into dream, into the threads of a poem in five parts. How do “sensations, emotions, instincts, memories, anticipations” slip into the dream texture, I wonder. Into the making of a poem.

When Amy told me she had dreamed about me, I felt as if my

own life were like that dream in which you climb some stairs

in your house and discover an additional room, or a whole

series of rooms, you didn’t know was there.

SPACE

A word with myriad possibilities. There is space in the reading, in this nourishing process of reading that sends me looptracking and dawdling in a state of dream and wonder. Early in the sequence Anna is (and yes usually I am cautious about attributing the speaking voice to the author, but this book feels utterly personal so I think of the voice as Anna’s) – taking photographs of squares.

There is too the proximity of space and death, especially as both Anna’s parents and sister had had “a turn at death’s door”.

There are recurring motifs of rooms and buildings, and especially this thought:

I thought, every body is a memory palace.

And this:

I thought about the concept of ‘peripersonal space’, the idea

that your mental mapping of the self includes the immediate

space around you, and what you habitually keep about your

person, including for instance your bag, or your falcon.

READING LIST

Lately, I have been reading novels and poetry books that make a writer’s reading history visible. I love falling upon titles to be added to my must-read notebook, across genre, time, location, languages. Anna’s reading list at the back and the titles sprinkled throughout is incredible.

How may times do I return to Virginia Woolf! I must read Jan Morris’s thought-a-day diary, or Robert Wyatt’s irony of doing loads of minimalism, and how I too loved Susan Stewart’s magnificent On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, The Gigantic, the Souvenir, Olivia Lang’s Crudo, Madison Hamill’s brilliant Specimen, Muriel Rukeyser’s poetry.

SELF LOOP

Worrier, Terrier is the kind of book you can’t put down. I keep giving myself another week to flow along its currents, neither to explain nor pigeonhole, but to embark upon the joys of reading poetry, of reading a book that feeds your mind, that sparks and startles your memory banks, that gets you revisiting your own secret feelings and thoughts. Because more than anything, I hold Terrier, Worrier as a book of self. This book of invigorating return, where you will find yourself expanding with both recognition and discovery. It feels like this is what Anna did as she wrote. Is the poetry a form of coping with the abysmal world, the drift thoughts and non-thoughts, the dailiness, the relationships?

I read another page. Then I reread this, a pulsating heartcore of the book:

Some feelings expand the self like a gas into the world and

some condense the self into the coldest matter.

And then this:

I wondered whether I could hear ‘terrier’ as a version of the

word ‘worrier’, a worrier being not someone who makes you

worry but someone who themselves worries, who worries away at things like a terrier might worry away at a sock. A terrier would be someone who allows themselves actually to indulge in the feeling of terror. I tell myself, ‘I am not okay, but I will be okay’, but maybe I need to stop saying that and release the terror, or maybe the terrier is not myself but represents someone else’s terror that needs to be heard.

Tomorrow I will pick up the book again, and find another gleam and thought spur. I want to sit in a cafe with you all, let our thoughts dream and drift and link, as we empty our coffee cups, pick up our pens, and catch both the dark and the sunlight slipping in . . . as we write through weeping, laughter, longing, with doors ajar and love strengthening. I utterly love this book of wonder.

Anna Jackson is the author of seven collections of poetry as well as Diary Poetics: Form and Style in Writers’ Diaries 1915–1962 (Routledge, 2010) and Actions & Travels: How Poetry Works (Auckland University Press, 2022). She lives in Island Bay, Te Whanganui-a-Tara, and is associate professor in English literature at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington.

Anna Jackson’s website

Auckland University Press page