“Many New Zealand poetry books left their indelible mark on me this year.” Chris Tse, NZ Poet Laureate

In the middle of the night when I can’t sleep, I sometimes tune into Radio NZ and catch programmes from the BBC, programmes that cover science, the arts, climate change, people fixing the world, sports, history, happy news. Voices from all over the world, voices across time.

Recently, on Witness History, I discovered the Three Marias, three Portuguese poets who feature on the BBC’s 100 Women list, a list that features ‘inspiring and influential women from around the world’. Maria Teresa Horta, Maria Velho da Costa and Maria Isabel Barreno wrote Novas Cartas Portuguesas (New Portuguese Letters) in 1972, at a time when Portugal was ruled by an authoritarian dictatorship and women’s rights were few. The poetry collection was banned after publication, the women faced imprisonment, and became globally famous. Copies were smuggled out of Portugal and translated, and applauded by Simone de Beauvoir and Margurite Duras and other feminists: ‘It set the western world on fire’. We get to hear Maria Teresa Horta, feminist poet, journalist and activist speak. She has published over 40 books and is now 87. Listen here.

Many of us have struggled this year, mourned the unspeakable atrocities inflicted upon Gaza and Lebanon, unspeakable and yet must be spoken. Many of us have loathed a coalition government dismantling and damaging systems that protect the lives of many, that honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi, that promote the wellbeing of children, teenagers, adults, and yes, the planet. And many of us have faced health struggles, whether mental or physical, family and personal tragedies, redundancy, reduced income.

I asked some poets how they continued to write poetry in this slam of global inhumanity in my 5 Questions series. It was a question I carried and continue to carry to both my blogs, and my own writing.

The voice of Maria resonates in my head, along with the Palestine poets writing and sharing poetry against all odds, the thousands and thousands and thousands of us who marched on the hikoi, in body and in spirit.

How to respond to 2024? How to present a suite of highlights? I invited a number of poets to write a paragraph or so on what they have loved this year – and the response has been incredible. Wide ranging, multi-hued, connecting. I have added a number of books to my must-order-read list, I have felt comforted, I have identified with so much.

Amy Margurite’s admission that her capacity to read fiction has been impaired by health issues resonates when health issues have also defined my year. Amy writes, “This year poetry has allowed me to go on. Every year poetry allows me to go on.” This I share. I can’t wait to read my way through her list of poems. Ah. The rejuvenating power of poetry. Murray Edmond applauds our terrific boutique presses and highlights the rewards of long poems (yes!). Chris Tse embraces our taonga Tusiata Avia alongside four outstanding local poetry collections. Bill Manhire sends me off in search of John Gallas’s sublime tanka. The joy of short poems! Yes! It’s on order! Anne Kennedy reminds me of books I have loved, notably Grace Yee and Helen Lehndorf. Robert Sullivan’s visit to Hone Tuwhare’s crib and legacy once again gets Hone singing in my ears. I finish with the uplift of Hana Pera Aoake’s piece, and her thoughts forming an exquisite and essential bridge between writing and reading, and how the mahi and aroha of others can resonate so deeply.

My 2024 highlights collage has expanded into three parts that I am posting today, Tuesday and Wednesday. Thank you, to all the poets who have contributed so generously. This feels very special.

Amy Marguerite

Earlier this year, I decided I was going to keep a monthly record of all the poems and songs I found myself loving, questioning, returning to. This has kind of felt like keeping a diary, except a diary in which I never actually write about myself but always actually do! Whenever I revisit these records, these lists, I notice something new and layered about my condition that month and I think I really love this? Yes, I do really love this. I welcome the startle.

There are so many beautiful books I wish I’d read this year, but sadly my capacity for prose has been severely restricted due to some persistent health issues. But I have read many, many poems and I have listened to many, many songs, and every single one has been there for me in exactly the way I’ve needed it to be, which is to say they’ve all managed to ‘give credit to the real things’.[1] Poetry in particular has provided incredible relief, and by relief I don’t necessarily mean escape (although I absolutely turn to poetry for this). If you’ve ever repeatedly attempted to describe twenty seemingly discrete symptoms to a doctor in a single, fifteen-minute appointment, I think you’ll understand me when I say that poetry has provided—continues to provide—some long-overdue validation. So what I mean by relief is really the feeling of being able to go on. Every year poetry allows me to go on.

If you’re interested, here’s a list of some of the poems I’ve read and adored this year.

[1] Weyes Blood, “Movies”

Chris Tse

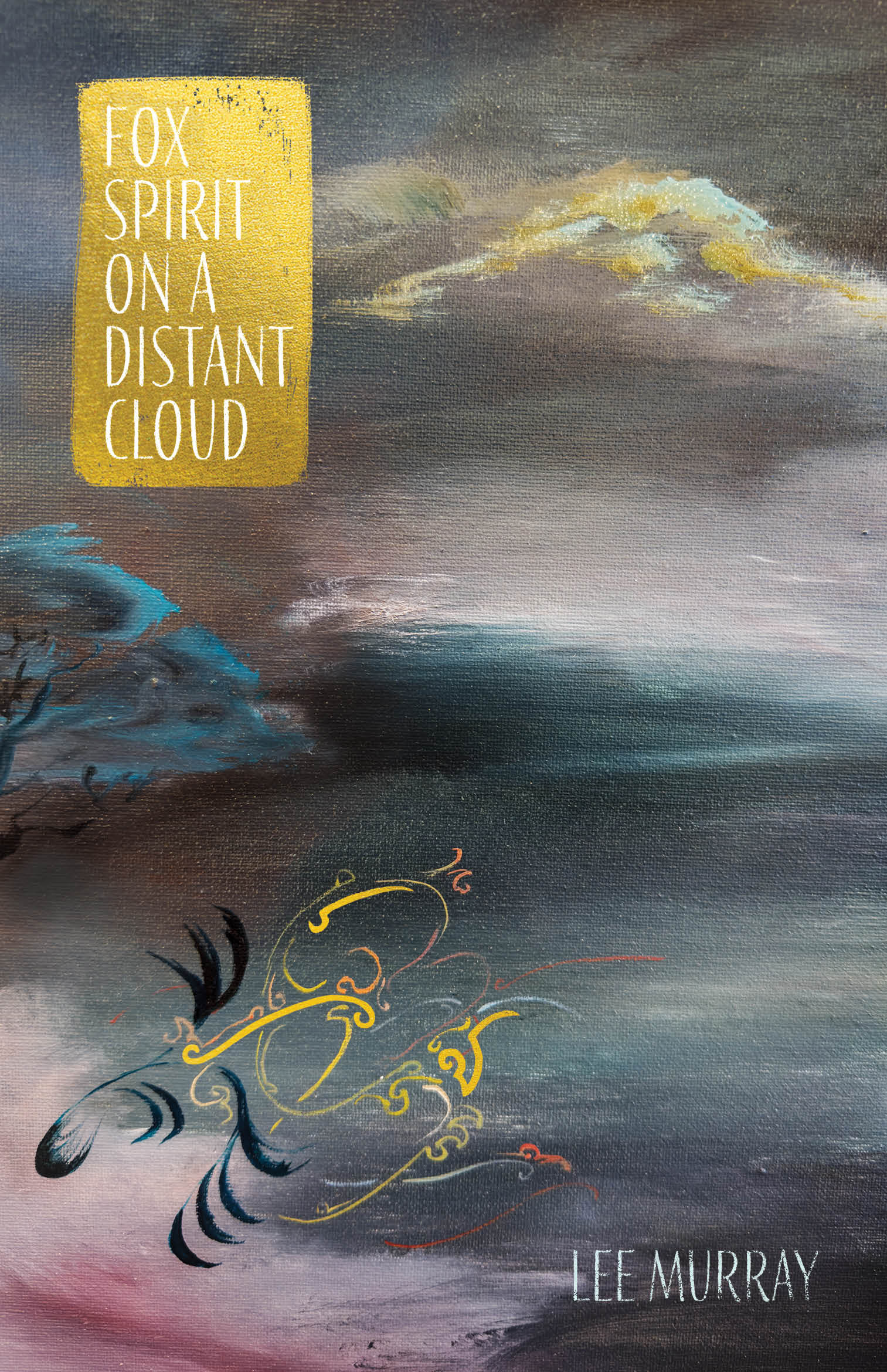

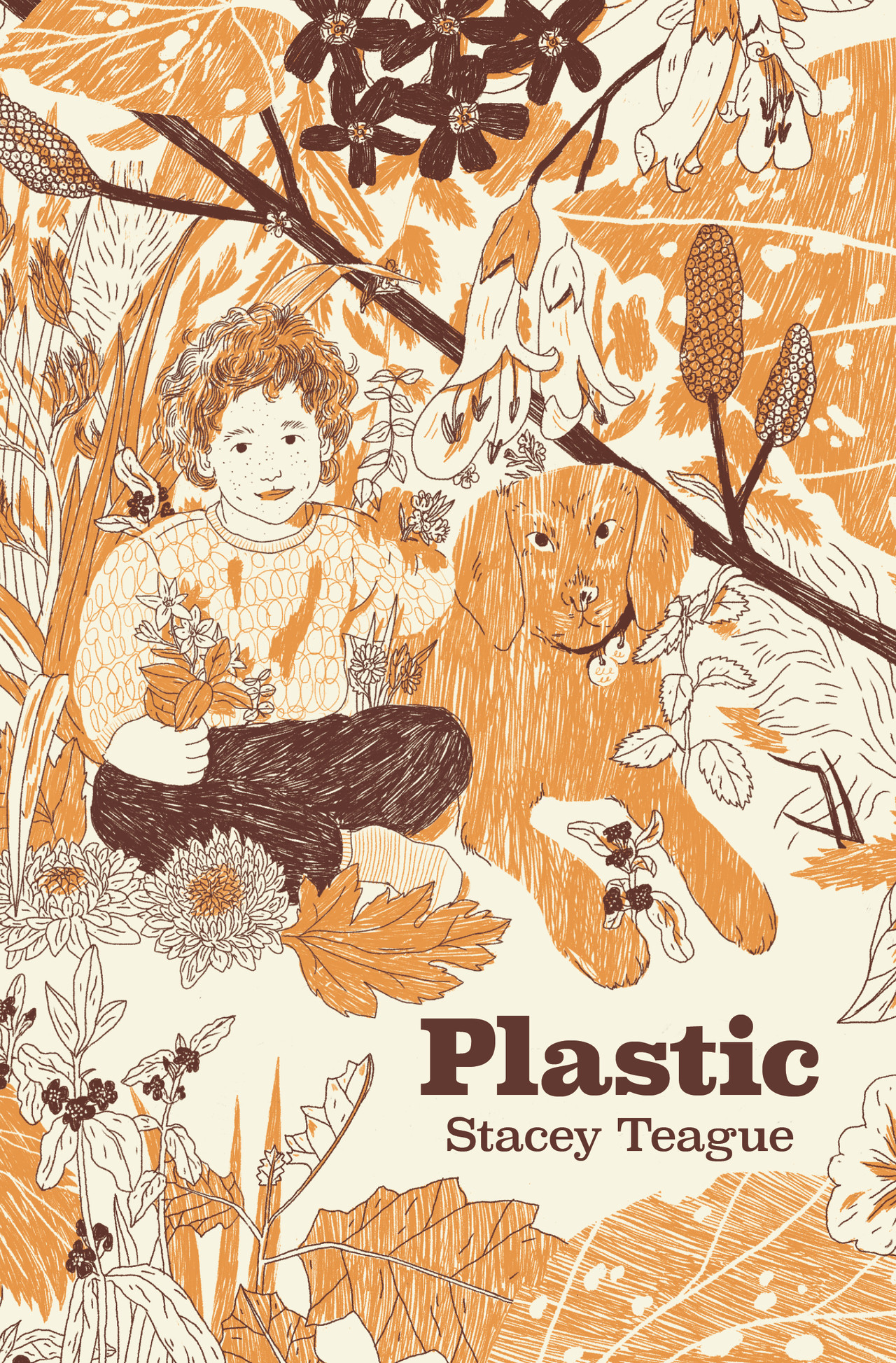

A highlight of the year for me was finally getting to watch The Savage Coloniser Show, a triumph of poetry and theatre that will no doubt be talked about for years to come. Hugest of congratulations to the show’s cast and crew for bringing Tusiata Avia’s poems to the stage with such ferocity and humanity. Many New Zealand poetry books left their indelible mark on me this year, including Tracey Slaughter’s The Girls in the Red House are Singing (THWUP); Stacey Teague’s Plastic (THWUP); Lee Murray’s Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud (Cuba Press); and Rex Letoa Paget’s Manuali’i (Saufo’i Press). And it’s been wonderful to see New Zealand writers making waves around the world, like Megan Kitching and Robyn Maree Pickens being recognised by the 2024 Laurel Prize judges, Rebecca Hawkens winning in US journal Palette Poetry’s 2024 Sappho Prize for Women Poets, and novels by Rebecca K. Reilly and Saraid de Silva being published overseas to much acclaim.

Anne Kennedy

Three highlights for me, in a year full of wonderful reading experiences:

Chinese Fish, by Grace Yee (Giramondo). This stunning debut verse novel tells the story of family immigration to Aotearoa, mostly from the point of view of women. The thing that hits you first is the daring form – layered prose and poetry that is sometimes discursive, sometimes taut, always surprising. What this technical highwire act achieves is a telling that is heart-wrenching, informative, funny, original. I read this book in different ways – which to me is the sign of a great book. I gulped it down compulsively, I lingered over bits and went back to them, I and went back to the whole thing. One of my favourite books of all time.Chinese Fish won both the 2024 Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry in the Ockham Awards, and the Victorian Prize for Literature in Australia, and you can see why.

A Forager’s Life: Finding My Heart and Home in Nature, by Helen Lehndorf (HarperCollins). I was late to the party for this 2023 book, but loved reading AND listening to it this year. Poet Lehndorf brings her extraordinary gifts to a book that is part memoir, part edible-plant guide, part how-to manual. I was enthralled with the contrasts in Lehndorf’s life: country girl discovers Punk, working class girl goes to uni (a poignant story in itself), young woman’s OE is spent not hanging around Earl’s Court but foraging in the wilds of her ancestor’s Britain. Each chapter ends with a recipe. As a reader, full disclosure: I am never going to make a healing tincture out of kawakawa. Doesn’t matter. The recipes are beautiful to read, and they amplify the beautiful storytelling here. A must-read.

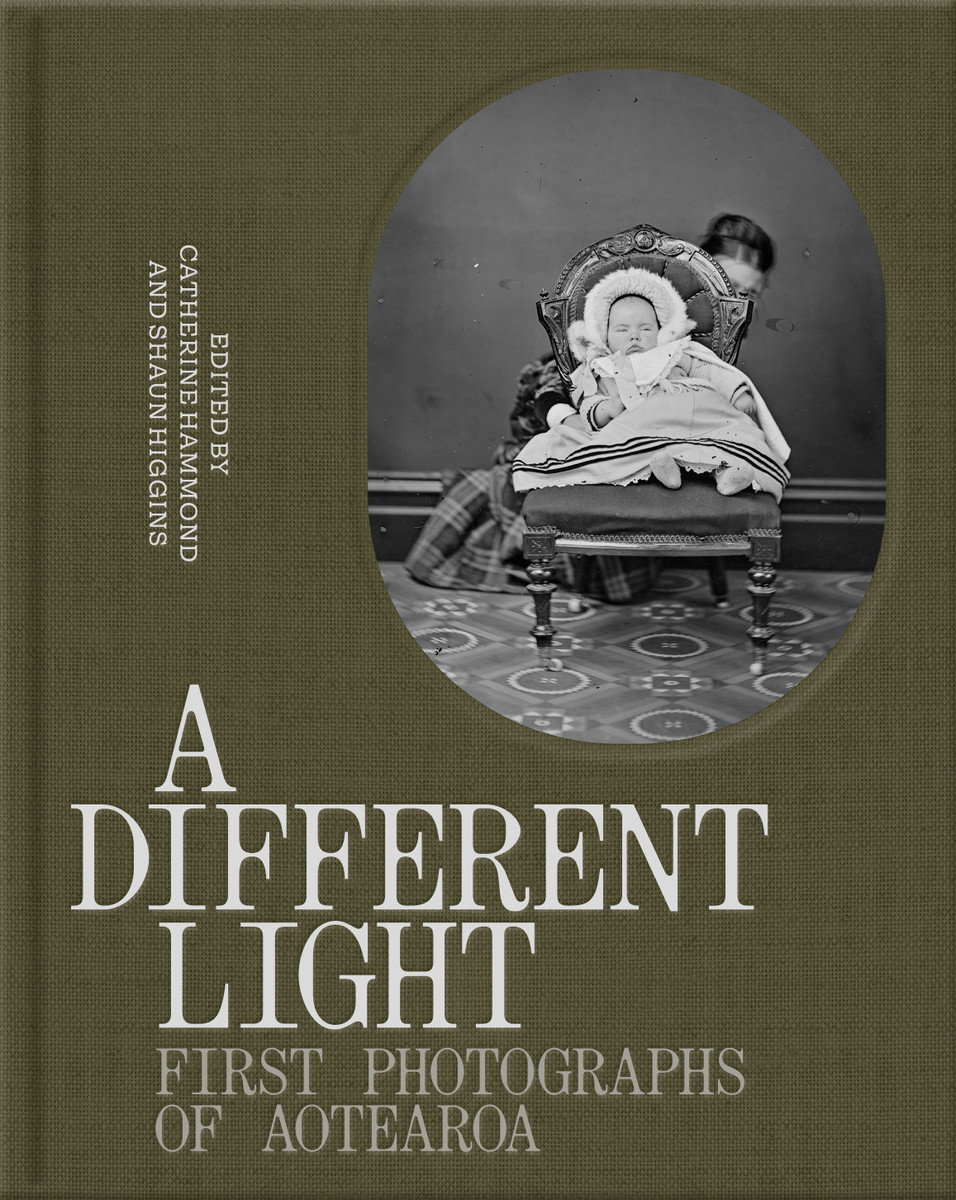

A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa, by Catherine Hammond and Shaun Higgins (AUP). The book of the exhibition at Tāmaki Paenga Hira / Auckland Museum. It’s a treasure – lovely production with lots of plates, informative, moving as it shows and tells stories of Aotearoa’s photographic past.

Bill Manhire

John Gallas: Billy ‘Nibs’ Buckshot: The Complete Works

John Gallas is one of the most prolific yet mysterious figures in New Zealand poetry. He has spent most of his adult life in the UK, yet visits New Zealand frequently. I interviewed him a few years ago in Sport, where he quoted approvingly a reviewer who said his poems were “funny, melancholy, and just plain weird.” His latest book from his loyal publisher Carcanet is true to form in a number of ways. It’s certainly weird and funny and melancholy. It’s also a book of tankas, a Japanese form which – at least in this outing – is rather more demanding than the haiku. Each poem has five lines. The first has five syllables, the second seven, the third five, while the fourth and fifth each have seven. Here there are 198 such tankas – each with a title, and double-spaced on its own page. So much white space! Each of the poems seems to float. Many of them seem to involve riding around England on a bicycle while thinking about other things, sometimes indeed words and places back in New Zealand. Here’s one called ‘The Voice’:

When I pump up the

old accordion, it hoots

and squeals and sighs with

merry anticipation.

Are you in there, my darling?

And maybe one more called ‘Summer Song’:

Remember when dad

led us up Mount Robert ridge

through a hall of snow

higher than our heads. I miss

the bright struggle of winter.

Murray Edmond

One highlight for the year has been the continued output of volumes from the small presses. Here are eight examples from five different presses:

Compound Press with Alison Glenny’s /slanted and Craig Foltz’s Petroglyphs; Spoor Books with Richard von Sturmer’s Slender Volumes; Lasavia Press with Mike Johnson’s Love in the Age of Unreason, Leila Lees’s Hekate and Lindsay Rabbit’s Poems & Images; Titus Books with Carin Smeaton’s Hibiscus Tart; and, from Australian small press Vagabond, Titus and Atuanui Press’s founder and editor, Brett Cross’s first volume of his own poems, Islands.

Another highlight has been the joy of reading long poems. Ranier Maria Rilke’s ‘Requiem for a Friend,’ in memory of the painter, Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907), is a ‘short’ long poem (more than 270 lines). In the face of “wrenching the till-then from the ever-since” in relation to her early death, Rilke says of the painter’s work: “you saw yourself as a fruit.” Searching to articulate what this might mean, he writes: [you] “didn’t say I am that. No: this is.” Grief at the loss of his friend brings the poem to that Horatian conundrum: “an ancient enmity/ between our daily life and the great work.” The 44 pages of James Schuyler’s The Morning of the Poem celebrate daily life as he lived it on “July 8 or July 9, the eighth surely, certainly 1976 . . .“ and, in doing so, he gives as a poem that stands up as ‘a great work.’ Byron’s uncompleted 16,000-line Don Juan is a ‘long’ long poem. Cantos VII and VIII are a full account of the Russian siege and capture of Izmail, then a Turkish/Ottoman town and fortress, during the Russo-Turkish War of 1787-1792. The Russian commander ordered Izmail taken “at whatever price.” Once captured the Russian soldiers were granted three days of carte blanche – 40,000 Turkish, Moldavian, Armenian, Jewish men, women and children were slaughtered. On 27th September 2024 the Russian military launched a drone and missile attack (drones first to distract from the missiles to follow) against the now-Ukrainian town of Izmail. Poetry can’t stop the bombs, but it can keep us ‘up-to-date’ with the past as well as the present.

Robert Sullivan

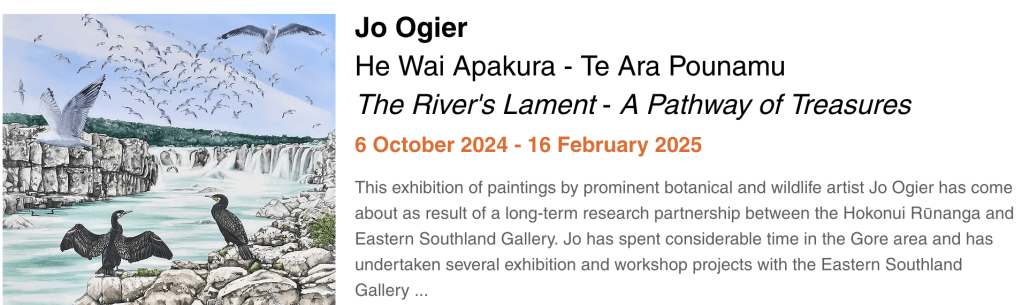

Kia ora everyone, one of my highlights this year has only just happened. It was my second visit to the Hone Tuwhare crib at Kākā Point in the Caitlins. The Hone Tuwhare Trust led by Jeanette Wikaira and Rob Tuwhare marshalled the expertise, efforts and aroha of Hone Tuwhare’s huge community and whānau to restore the crib. Big Congratulations to the Trust and their many supporters who have also established a writers and artists’ residency. After visiting Rob and Manaia Tuwhare at the crib and having a kai (venison!) and a kōrero there, we went on into the Catlins—the forests, Cathedral Cave, the Pūrākaunui Waterfalls, swimming at Papatowai estuary and then driving up the Owaka Valley to Mataura to see the effects of industrialisation on the Mata-au or Clutha River, and then into the amazing Gore Museum with the Ralph Hotere collection rich in poetry from Hone Tuwhare, Cilla McQueen, Bill Manhire and Ian Wedde and art from Marilyn Webb. One amazing part of the collection was the resurrection of the Mata-au through the imagination of botanical and wilidlife artist Jo Ogier. Her series of bird, fish and water-scapes, called “He Wai Apakura – Te Ara Pounamu, The River’s Lament – A Pathway,” was painted with support from the Hokonui Rūnanga of Kāi Tahu. Instead of the freezing works, and the abandoned papermill, there was a healthy river with its endowment of native flora and fauna. The exhibit by Jo Ogier will be there until the end of summer.

Jo Ogier exhibition

Hone Tuwhare crib

Hana Pera Aoake

My favourite collection of poems I read this year was Schaeffer Lemalu’s the prism and the rose and the late poems; published posthumously on Compound Press. When I write poetry I struggle with its simplicity as a form, or rather how to extricate a feeling or experience into a simple collection of words meaning my poems are always really long and due for a line edit when I eventually let go of trying to relay everything I can into one poem. Sometimes you need to just let words rest and give them space and that therein give these ideas power and an ability to percolate. Lemalu mastered this, but still sought to fuck with poetry as a form by making it conversational as though he is directly speaking to you. At other points he becomes others from anon or sean.smith or nolans bateman. He wrote through and outside the body. His poems elicit something so bodily that makes you want to observe more around you, such as the sensation of gently peeling a mandarin while reading a book and observing someone save a bee trapped in the middle of a swimming pool with their hands. It’s gentle, but cutting and although sometimes tightly structured, other times its loose and playful.

this is my rifle

this is my gun

this is for fighting

this is for fun

this is my rifle

this is my gun

this is for fighting

this is for fun

i want to see your whips

in my study break after

o how was india enjoy it

like that

from ‘2 the prism and the rose a digital manifesto by nolans bateman’

The central treatise of the book is the prism and the rose a digital manifesto by nolans bateman which is perhaps that most difficult to decipher, because all of these other voices spill out onto the page and it’s hard to know when it ends, but you don’t want it to end. His work appears deceptively simple even when there is an echo or a repetition of certain ideas or phrases or images, it’s always done in a way that’s completely unexpected and something funny, but not in a hahaha way, in a way that is mischievous.

For instance

anyone can have a brain

its a very mediocre commodity

from ‘3 the prism and the rose a digital manifesto by nolans bateman’

batman

batman

whys he running dad

because we have to chase him

from ‘7 the prism and the rose a digital manifesto by nolans bateman’

At times he blends films, from The Last Samurai, The Wizard Oz to The Sound of Music to his will and aligns them alongside more brutal realities such as mother on benefits or a line acknowledging the work of Erza Pound or the Italian poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini or a subtle nod to Frank O’Hara’s A coke with you.

pasolini said history does not exist shortly before he died

from ‘like a peacock fanning its eyes’

Lemalu’s poems hit really quietly and he could convey so much with only a few words, so there is room to breathe around a bricolage of different cadences . Yet the collection is full of surprises, of tiny little glimpses of life, whether that be joy, death, love and the fragility and transience of everything around us whether that be the blossoms in nights for days and neo.

search for the perfect blossom

and you won’t find it

they are all perfect

Every time I have re-read it I find something different and there are parts I find difficult until I read it aloud and try to imagine how he might have read it and what his voice might have sounded like. I never met him, but having seen some of his paintings, I think they speak to his poems in terms of the subtlety and playfulness, particularly with how he used colour. There is something of a childlike wonder or longing that I cannot quite articulate, but this is a book I will return to again and again and I’m grateful to Chris Holdaway for working with Lemalu’s whānau to publish his words. This collection is bittersweet, because I want to read more of his work, but he’s no longer with us and when I think about this I recall Donald Revell’s introduction where he notes that

‘His word is among us, travelling still’

The other three poetry books I think were very important for me to read were Liam Jacobson’s Neither (Dead Bird Books), Carin Smeaton’s Hibiscus Tart (Titus Books) and Maggie Nelson’s Bluets.

Liam Jacobson’s poems are unruly; they take you in unexpected places and illuminate Tāmaki Makaurau in new ways that are not nostalgic nor cliche. They also made my heart ache and helped me nurse certain heartaches I was experiencing while reading this book.

dream-time whispers at stars

crackers n cream whippers from KRD Mart

a city in a coma shaken awake, a ghost town past the horizon’s end

from ‘BUS TO K’

i remember your hands soaked in oil

before everything started following

& i fell

which one of us feels like this?

i’d leave my body for u

i’d leave my body for u

from ‘SOMETHING FOR TOMORROW UNLESS YOU HATE IT’

Carin Smeaton’s Hibiscus Tart goes down many paths, she is cheeky, gives respect to slang and holds in her hands different ways of loving the whenua and offering an honest appraisal of what it means to be Indigenous in a colonised world. Sometimes I think I’m going down one wormhole only to be jolted down another only to be bitten around the corner of another. She grasps complicated and disparate ideas and forms of languages and sculpts them into porous poems that swim in your head for days afterwards. I want to read more poetry like this that doesn’t give a shit about the rules and flips images on their head and spit roasts them with fire spitting out of her fingernails one word at a time.

burning bye into

yr ancestral wings

let them go hun

they’d never make it

thru customs anyways

crammed into yr suitcase

like a whakapapa happy meal

from ‘meghan markle’s sister’

Before whales swam they flew thru the blu stars of life on

earth she calls for her orcas her children her babies to gather together

she’s ready she says to return

from ‘flying whales on earth’

Finally I re-read Maggie Nelson’s Bluets on a flight from London to Auckland. I had just seen a theatre production of Nelson’s meditation on the colour blue at the Royal Court theatre with Emma D’Arcy, Ben Whishaw and Kayla Meikle. The performance saw the three performers standing with a mic and a tray of props and a screen behind them. I hated it. I feel that Nelson’s book is very distinctly American and the lyrical, sensuous and incredibly visceral and beautiful heartbreak of Bluets needs to be read not performed. On a sentence level Bluets is so elegant and is numbered like a manifesto. The way she blends the essay and poetry, the theoretical with the explicitly sexual pulverises your insides. It’s disjointed, but never feels that way. It’s terrifying and profound and conjures up so many different associations, memories and emotions. It distills the ecstasy of falling in love and having your heart broken in a way that I don’t think any other book has ever or will ever do as well. It’s still so powerful nearly two decades after it was published and I’m glad I re-read it and cried and cried. It’s definitely a book to give to someone you love who is in pain.

238. I want you to know, if you ever read this, there was a

time when I would rather have had you by my side than

any one of these words; I would rather have had you by

my side than all the blue in the world.

156. “Why is the sky blue?” -A fair enough question,

and one I have learned the answer to several times. Yet

every time I try to explain it to someone or remember it

to myself, it eludes me. Now I like to remember the ques-

tion alone, as it reminds me that my mind is essentially a

sieve, that I am mortal.

Non poetry books I read this year that were fucking great include Talia Marshall’s Whaea Blue, Emma Hislop’s Ruin, Catherine Comyn’s The financial colonisation of Aotearoa, Ursula K Le Guin’s The carrier bag of fiction, McKenzie Wark’s Philosophy for Spiders: On the Low Theory of Kathy Acker and Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow.

Pingback: Poetry Shelf 2024 highlights collage – part two | NZ Poetry Shelf

Pingback: Poetry Shelf 2024 highlights collage – part three | NZ Poetry Shelf