On Thursdays, Poetry Shelf will post a series entitled ‘Poets on Poems‘. The poets and invited guests will muse on a favourite poem, especially New Zealand examples, and the poem will be included with permission. I love the idea of drawing poems out of the shadows, of underlining how we can be readers as much as writers, how poetry can evoke such diverse responses, epiphanies, pleasures. How it might comfort but also might challenge. How it underlines the sublime and satisfying reach of words.

Bill Manhire has a regular column in North & South where he writes about poems and poetry. His latest piece (April issue), considers witty lines: swerves, teasings, humour, the sizzle of the ordinary, ‘a deflation effect which is sometimes called monostich’. He includes a terrific poem by Jessie Mackay and a musing on the brilliance of James Brown (James has a new book out in June or July).

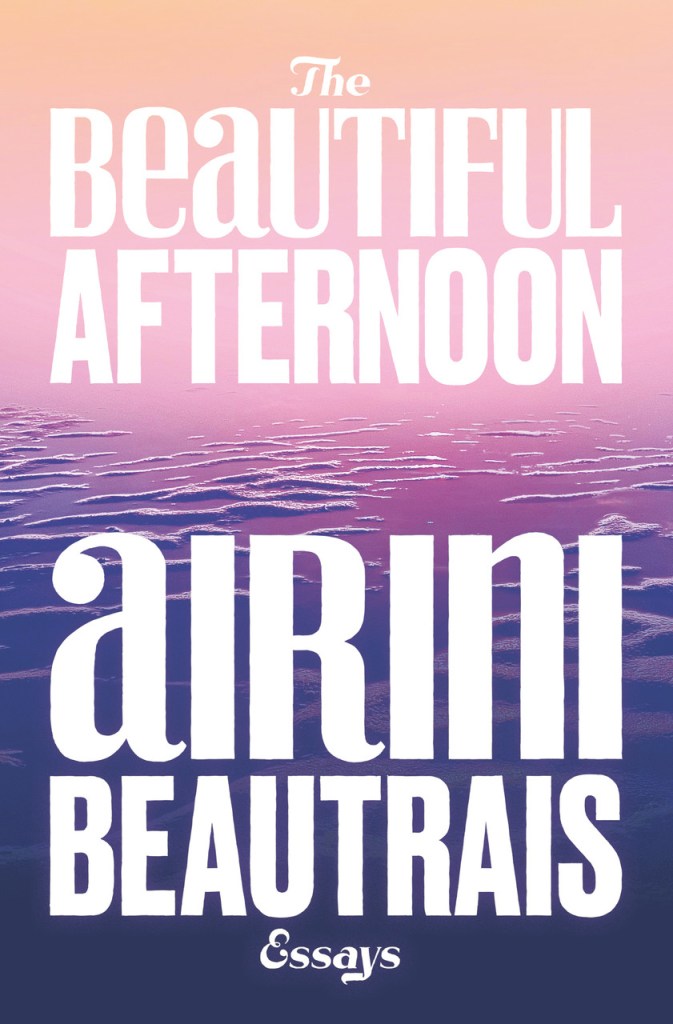

To launch the Poetry Shelf series, Airini Beautrais has contributed an excerpt from The Beautiful Afternoon, her new book of essays, a book that engages with life and difficulty, resolve and multiple fascinations, including poetry and reading, on so many levels.

From ‘Silent Worship’

In a 1966 ‘fragment’ poem, Rachael Blau DuPlessis writes:

I, Lady, you are my true love’s lady.

You stand in the middle of the room,

Sunlight streaming around you.

Sunlight takes hold of the seeds in you

And wets them.

I want to hold myself to you,

But you are myself. Can I?

In considering the coexistence of ‘I’ and ‘Lady’, DuPlessis asks questions about who is allowed to speak. In her essay ‘Manifests’, in which this fragment is quoted, she asks: ‘Am “I” forbidden to poetry by one – but one key – law of poetry, the cult of the idealized female?’ DuPlessis goes a step further into botanical imagery by incorporating ‘the seeds’, implying both ova and semen. Wetting one’s own seeds, holding oneself to oneself, could allude to masturbation, but more is going on here. If we can’t speak in poetry, the oldest literary language of the world, in what medium can we speak? If we can’t speak for ourselves, all we can be is spoken to, or spoken of.

Where do women go when we are no longer deemed physically attractive by dominant beauty standards? When our boobs droop and our waists thicken, our spines curve? Where do women go who have never been perceived as attractive? Who no longer want to be attractive, or have never wanted to be? Where do people beyond the gender binary, beyond heterosexuality go? The centring of heterosexual romance leaves out a lot of people and a lot of possibilities, pushed to the edges, the wilderness beyond the garden. In the literary canon, there are ghosts, whispers, occasional glimpses. In the gardens made by men, uncertain shapes glimmer underneath the trees, or flash briefly across the sun. Who was also, always there? Whose seeds were always planted?

One day, recently, I was talking to my science students about sand, how sand is a mixture of broken bits of shell, rocks, organic matter. Sand looks like it’s uniform if you hold it in your hand, but if you look at it under a microscope, you can see all the different parts. I thought about the William Blake poem ‘Auguries of Innocence’:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

I thought about how we are able to see beauty when we turn our attention away from performing or spectating it. How difficult it is to see a world in a grain of sand when you’re socially conditioned to be meditating upon the flaws of your figure and face. What does it mean to let go completely, to go into the organic world, to get your hands covered in soil, to sow your own herbs, to mutter your own spells? As I moved out of the state of being a woman in a long-term committed relationship and into the state of being a single woman, a single mother, a difficult woman, a woman who spoke openly about her experiences, I also made spiritual shifts. I moved from an afterglow of Christianity, my liberal Quaker upbringing, further into a desire to seek out connections with nature and the occult. My maternal grandmother was raised as a Scottish Presbyterian, but mostly believed in nature spirits and fairies. In every garden, she told us, there should be a wild place where the fairies can live. Threads of Celtic paganism ran down through the maternal generations of our family, in spite of the overlay of devout, churchgoing, Protestantism. Multiple people in the family have been visited by the dead after their passing. I don’t have words or understandings to describe all of this, but I do have a word for what is implied: power. In the garden, in the forest, in the wild spaces, both externally and within ourselves, is where it lives.

After my separation, it took me some time and legal wranglings to get back into the house I had left. Once I returned, I had a sense that things that had happened there needed to be exorcised. There was a bad smell and a bad energy in the house. It was mostly empty of furnishings, and it hadn’t been cleaned in several months. The garden had not been tended. Anything motorised or stereotypically masculine had also gone, including the lawnmower and the weed-eater. I was on a tight budget and had a number of appliances to replace. I decided not to replace the mower or weed-eater. I would turn the entire lawn into garden. While a family court psychologist interviewed my children inside the house, I worked outside, moving rocks. Big lumps of shellrock had been piled into a large mound in the corner of the section by previous owners of the house. Now I was clearing this mound. The rocks were sharp to the touch, filled with the fragments of million-year-old shells. I wore gloves. One by one, I carried the rocks, placing them in the shape of a heart, in the centre of the front lawn. Later, I filled in the heart with cardboard and mulch, made other shapes around it. I lifted heavy chunks of broken concrete, set them in a circle, built a fire pit, surrounded it with river pebbles. I planted fruit trees. I made a pond, which sat green and murky in the corner. I hung wind-chimes in the trees. Gradually, the suburban lawn gave way to what felt like a magical space. For my thirty-fifth birthday, my seven-year-old enlisted the help of his grandmother to buy me six rose bushes. I planted them within the rocky heart.

European and colonial American Christians burned, drowned and hung people they deemed witches because witches represented the things they were most afraid of. One of these things was female power, which across cultures has resided primarily with older women. People of all ages and genders have been put to death accused of witchcraft, but the ageing woman was a favourite target. The problem of contemporary ageism is that it encourages us to silence ourselves, to worry about our physical attractiveness when we are spiritually ready to inherit the fullness of our capabilities. Biologically speaking, there is no consensus on the reasons for menopause. Only humans and a few species of whales go through it. It may be an evolutionary irrelevance. Spiritually speaking, the older woman is vital to the workings of the community. In pre-Christian Europe and in cultures around the world, we find her in central roles: as midwife, wise woman, herbalist, soothsayer, witch and queen. If we are distracted from our power, we can be prevented from exercising it. If we are encouraged to resent younger women, we will refuse to help them. We will see them as enemies. Our intergenerational wisdom will be fractured and diluted. Pitting women against each other in a competition where men are the prize is one of the crudest but most successful tactics of patriarchy.

In 2022, a couple of days past the winter solstice, I walk around the lake. The first magnolia buds are opening on the same trees, revealing white petals. Looking at the trees, I remember the spring six years ago, when the sight of the flowers seemed synonymous with the emotional pain that physically ached inside my chest, and churned my guts, when I projected body dysmorphia and internalised misogyny and ageism onto an annual botanical event. Now, feeling no pain or heartbreak, I feel an immense sense of freedom. I am walking with no concerns other than walking. On the top path I pass two women in their sixties, with dyed hair and bright pink lipstick. We are strangers but we greet each other warmly. A trail of scent remains behind them. Pink camellias are bursting with flowers. Bees are working the stamens. The sun is out and I turn my face towards it, feel its warmth enter my skin. The spring belongs to no one, signifies nothing human. A tree is not a person: it comes into leaf, fruits and sets seed annually, following its own cyclical rhythms.

I have not lost my fear of ageing. That goes too deep to deal with in a matter of a few years. It is part of a normal human fear of mortality; it is also heavily socialised into me. I still have difficulty looking in a mirror and seeing the deepening lines on my face, the changing texture of my skin, the thinning of my hair, the loosening of everything. What I have lost is the conceptualisation of my life as something with romantic love as its central aim. This is a difficult thing to lose. I don’t know many people who feel the same way. Most of the single women I know are trawling dating apps, or their limited pool of acquaintances, for someone who might be a reasonable long-term partner. Most of the divorced women I know still believe in marriage.

When the solstice passes, and the days become longer, I begin to sense a shift in the earth. It has always felt to me like a tingling in the nerves. For a long time, I have associated this with some kind of romantic longing. I have learned to associate sun and flowers with a beloved. I have done this since I was a pre-pubescent child. Now, approaching forty, I am re-learning to enjoy this sensation as a sensation on its own. This time, the magnolias are just magnolias. Also, they remind me of some of my favourite lines of poetry, from Dinah Hawken’s ‘The Harbour Poems’:

Turned away from the lecture on sexual economics

she goes down into the sexual garden, under its dark spread

and into its detail: ecstatically branching magnolia, tuberous

roots thrusting up huge leaves. Fuck the tulips in their damned

obedient rows. Stop. They’re finally opening their throats!

They have dark purple stars! They have stigma! They have style!

Hawken’s description of the tulips in their ‘damned obedient rows’ suggests feminine submissiveness. But then, she abruptly changes tack. Stop. The tulips, so evocative of genitalia, are opening, and are finally able to speak. The puns on floral parts put a humorous twist on what is a call to power. The garden has been filled with female sexuality, with all sexualities, with female power, with humanity, all along. Nothing is silent, the garden worships itself. We are all able to go down through it.

Airini Beautrais

from The Beautiful Afternoon, Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2024

Airini Beautrais lives in Whanganui. Her collection of short stories, Bug Week, won the Jann Medlicott Acorn Foundation Prize at the 2021 NZ Book Awards. She is also the author of four collections of poetry and the essay collection The Beautiful Afternoon (THWUP 2024).

Te Herenga Waka University Press page