How to sing sunlight

Look at the light dancing on the waves

I say to Martha. She is five years old.

Sunlight is so hard to catch, she says

but it catches everything in the whole

wide world. She sings a song. I ask her

if she has learned it at kindergarten.

I’m making it up just now, she says

it’s what the sun is singing to the sea.

And runs off dancing her songlines

of sun and sky and wind and sea

elated all the way across the sand

into the wide open arms of everything.

John Allison

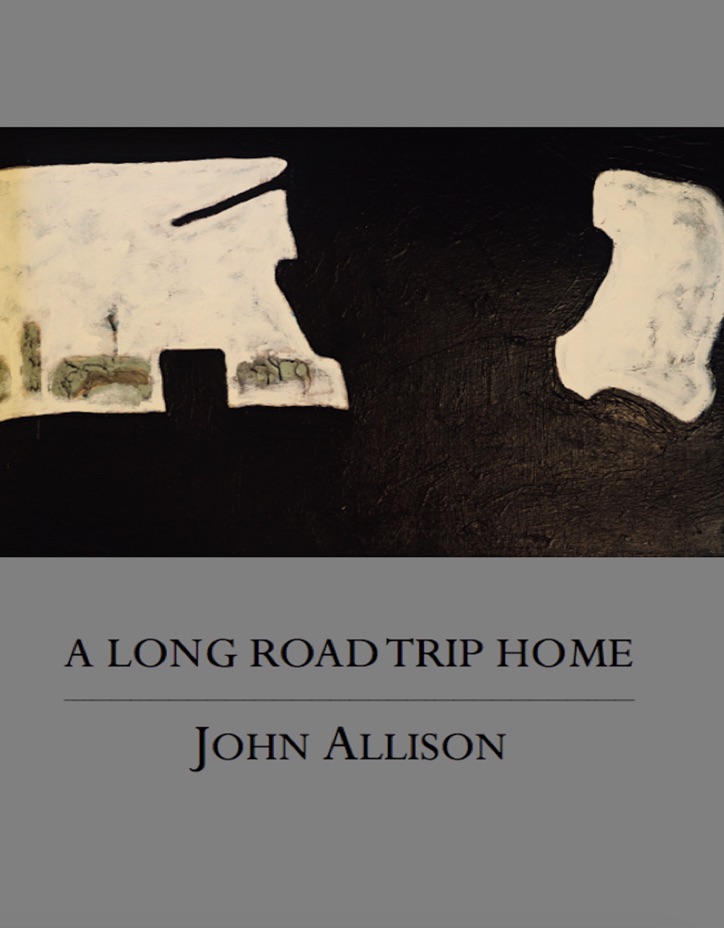

from A Long Road Trip Home, Cold Hub Press, 2023

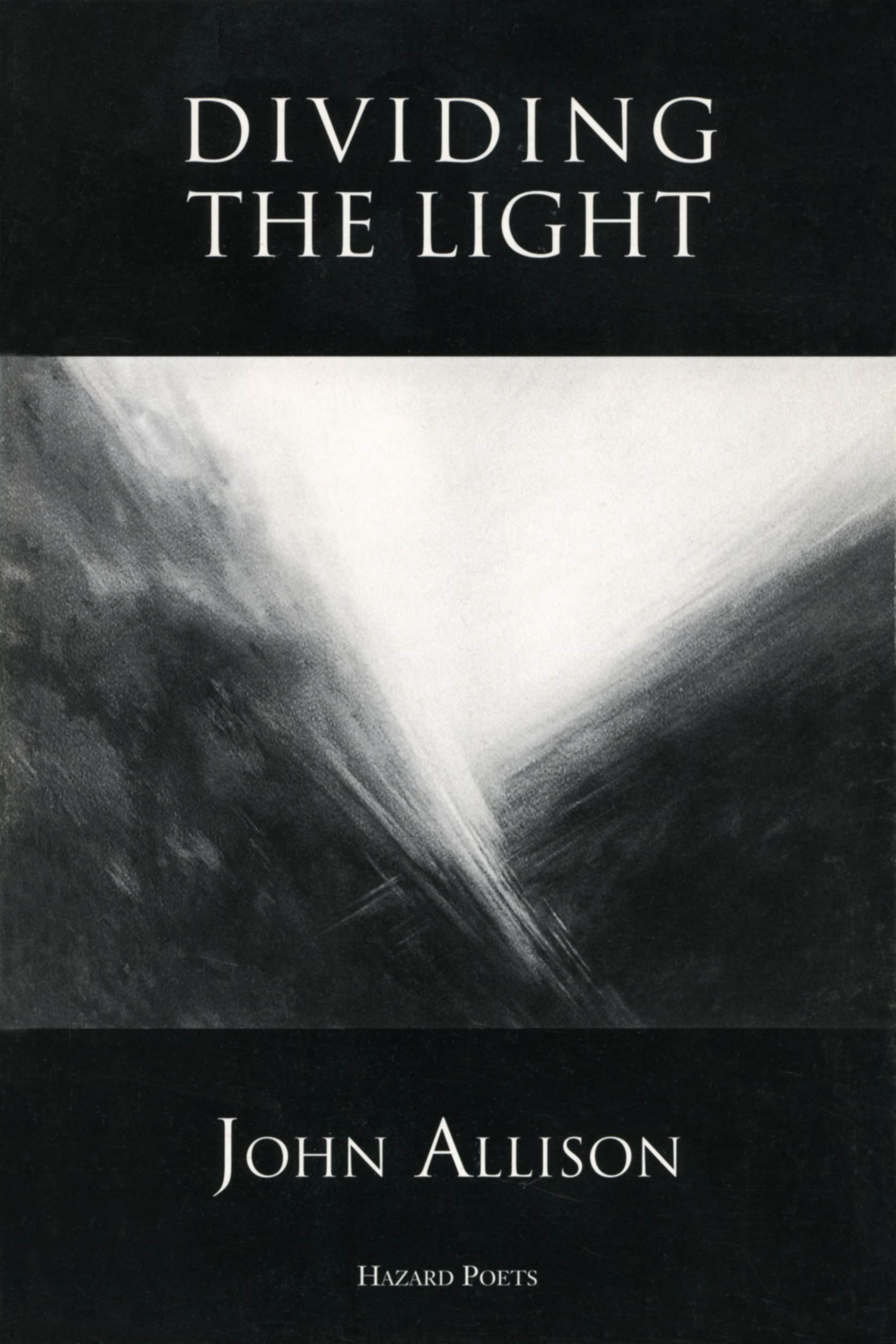

The recent death of John Allison (1950 – 2024), has touched local writing communities. Poet, musician, teacher and mentor, John published seven collections of poetry: from his debut, Dividing the Light in 1997 (Hazard Press), a number with Sudden Valley Press, Balance: New and Selected poems (Five Islands Press, Melbourne, 2006), and several with Cold Hub Press, including final collection, Long Road Trip Home (2023). He taught for several decades at The Rudolf Steiner School in Christchurch, co-founded Sudden Valley Press and was a key member of the Canterbury Poetry Collective. He was the featured poet in Poetry NZ 14.

To celebrate the life and poetry of John, Poetry Shelf has gathered written tributes, some readings of his poems, included some of his own poetry and reviewed his final collection. This is a special gathering, a meeting place with multiple clearings and poetry benches we can return to, to meditate, mourn and above all, celebrate.

Sudden Valley Press, The John O’Connor First Book Award page

Cold Hub Press page

‘Corona Contemptible’ on Poetry Shelf

‘Whitianga Testament’ on Poetry Shelf

‘Father’s axe, grandfather’s machete’ Ōrongohau Best NZ Poems 2020

Thank you to the contributors, and special thanks to David Gregory, Roger Hickin and James Norcliffe for helping me choose some of John’s poems and creating a list of people to contribute.

Go well, go gently.

A Review of A Long Trip Home

Of Bread

After all these years I’ve been

making bread again, remembering

that way your hands worked the lumpen

dough (who was it joked, the proles

also needed to be pummelled into shape

before they would rise?)

We were young, comrade

and our politics were too casual.

Later we settled for the word companion

meaning to share bread together.

And now after all these years I’ve learned

I cannot live by bread alone.

I become your hands.

John Allison, from A Long Road Trip Home

If you travel through John Allison’s seven published collections, the word ‘travel’ resonates deeply, both in his poetic fluency, the threaded and recurring motifs that range from the colour blue to the travelled road, from beloved artists to a rock pool, from the ever-present light to salty air, from the dead to the living, from listening and looking at the world to the anchor of home. Always ‘the long road home’; each poetry collection establishes sublime contemplation points on the long road home.

John’s final poetry collection, A Long Trip Home (Cold Hub Press, 2023), begins with a poem about baking bread. It’s hands on, evoking images of domesticity, fermentation, dailiness, the drifting thoughts as the dough is kneaded, the surfacing memories of the addressee, his ‘comrade’. The poem’s endnote refers us to Peter Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread (1892) and its vision of a society based on ‘mutual and voluntary cooperation’. The presence of the word, ‘companion‘, draws us deeper into what matters, into thoughts of companionship, and yes this haunting collection is poetry about what matters.

Turn the page and the poem ‘How to go on’ introduces this: ‘The ways back to reality / after the oncologist’s news’. Death is a companion we travel with as we read, whether John’s cancer diagnosis and his view of the world, the flickering arrivals of his horizon line, the planet at risk, recollections of those no longer with him such as in the poem ‘What is lost’, or in the eulogy to a friend, ‘the send-off’. A cancer diagnosis refines what matters and, out of that vital movement, John has written poetry that nestles under the skin.

More than anything, and as this tribute page underlines, people matter. Many poems are dedicated to loved ones, friends, other writers. He draws in his love of art and books; Colin McCahon, Vincent Van Gogh, Joseph Beuys, Roger Hipkin make appearances. He never forsakes his love of music, it is there on the line, sounding in your ear as you read. He is singing to friends, he is singing with the world, and the song invests what matters with finely crafted melody. In one poem, John is in a waiting room with a young girl drawing in blue, ‘in this waiting room where blue means something else’:

The girl glances up at us, and laughs:

You and my Daddy should make a song.

And she hums and she doesn’t stop the blue

yes, she hums and doesn’t stop the blue.

from ‘Singing the blues’

And yes, the blue reverberates with multiple meanings, as do so many of his words and motifs, and it haunts and it hurts and it uplifts, like music, like art, like the power and strength of poetry to nourish, and delight, and travel, and to remind us to open the window, to hold our arms wide, and to breathe in deeply what matters. This book is precious.

Paula Green

Tributes and Poems

For John Allison

The river of voice

runs on, even as

breath is stilled.

John, John, the muses’

son, breathed

his breath

and away

has gone.

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman reads his poem ‘For John Allison’

John Allison with David Howard and David Gregory, Banks Peninsula 1996

June 2019, same site on Banks Peninsula

David Howard

In his later years I saw John as a fresco painter on his way to the monastery. I imagined him sizing up a moist plaster wall. He would brush his colourful images into the surface.

As the wall dried, as its plaster set, every pigmented line John put there would join the lime and sand particles, becoming part of the structure rather than a surface decoration. His artistry made things more solid.

Skimming Water

these words are just

the sounds of

a smooth white stone

skittering

across the surface

of a pond

inscribing a brief

archipelago

of intersecting

lucent rings

arcing over

darkness

the stone

sinks

inside the

final

o

John Allison, from Stone Moon Dark Water, Sudden Valley Press, 1999

Singing the blues

She grips the felt-tip pen with that kind

of determination you’d never argue with,

hunched over the table and her drawing:

I’ve gotta finish the blue before we go!

It’s the only thing that’s being said here

in this waiting room where blue means

something else:

this feeling you have

for instance after getting the results of

your latest blood test;

of the evident

anxiety of the young pregnant mother

with colourful headgear and yellow-grey

pallor;

or the sadness of an older couple

bent and folded in towards each other

waiting between specialists, weighted by

the prospects;

or this grizzled old bloke

wheezing as he works a finger round

his gums, a sound more like a punctured

tyre than a tune you’d ever recognise.

But the girl with the blue felt-tip pen

colours and hums, and her father hums

as she colours, and looks out the window

at dark clouds and their promise of rain:

Yep, he says, it’s always a blue sky day

even though all of the clouds are grey . . .

Yes, I say, we’ve got to finish the blue

before we go, out of the blue it comes,

then into the bright blue yonder we’ll go.

The girl glances up at us, and laughs:

You and my Daddy should make a song.

And she hums and she doesn’t stop the blue

yes,she hums and doesn’t stop the blue.

John Allison, from A Long Road Trip Home, Cold Hub Press, 2023

extract from Of rocks and other hard places

1.

Rocks are slow stories carefully thought out

a friend has told me. Well it could be so . . .

Certainly these rocks I’m sitting upon

are quite reliable, content it seems to be

right where they are, grounded in that

reality we subscribe to, resistant to change

except through aeons and earthquakes.

Those are distinct eventualities, but

in between we find rocks usually sit tight.

They stay in touch. Gravity burdens them

yet they bear it all without complaint.

Like the dead they seem to be quite silent

(though like the dead, unless you lean

close to listen, you will not ever hear them).

Chatter is not their predilection. Ah, but

those opportunities for the big statement . . .

Knowing time inevitably is on their side

they do not want to waste their breath.

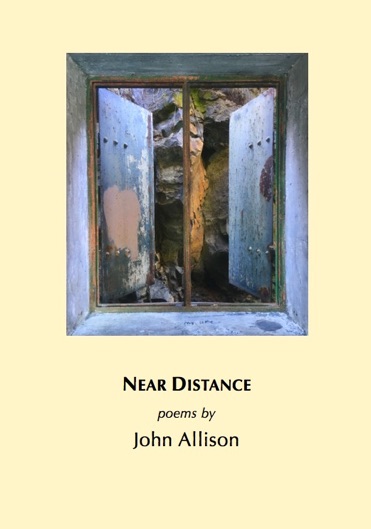

John Allison, from Near Distance, Cold Hub Press, 2020

Passage: a Closer Reading

Your book is in my hands.

I carry it around all week,

unopened.

Proximity,

however, makes us intimate;

the book begins to change.

The binding softens,

then the pages

wilt.

On the third day

I feel the words dissolve.

I’m not immune;

the images

absorbed like mercury

though fingertips,

their syntax

aching

in my wrists,

your poems make their way

virulent

towards

the lexis of the heart.

John Allison, from Dividing the Light, Hazard Press, 1997

A poem based on a painting based on a poem

Two or three years ago John wrote a poem called ‘the door’, the last poem in his final collection, A Long Road Trip Home. It is based on a small painting of mine he’d recently acquired––Devant la porte un homme chante (In front of the door a man is singing)––in which a door in a white wall is evoked by a swipe of black paint. The title is a line from a Pierre Reverdy poem.

John spent the last difficult ten or so years of his life acutely aware of that door that opens to the place that must be entered in order to arrive at what we are not. And he kept singing. To the end. Which might also be a beginning.

As he wrote (sounding just a little Sam Beckettish) in ‘the door’:

‘what is there to do until it opens/ but to sing’ . . .

Roger Hickin

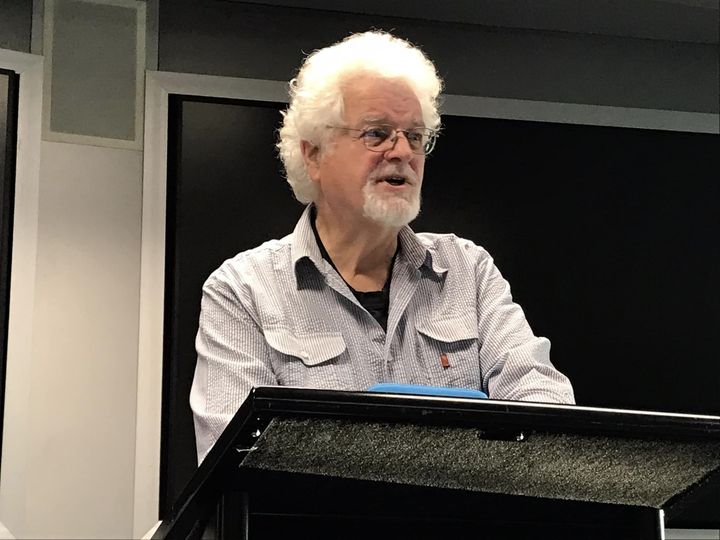

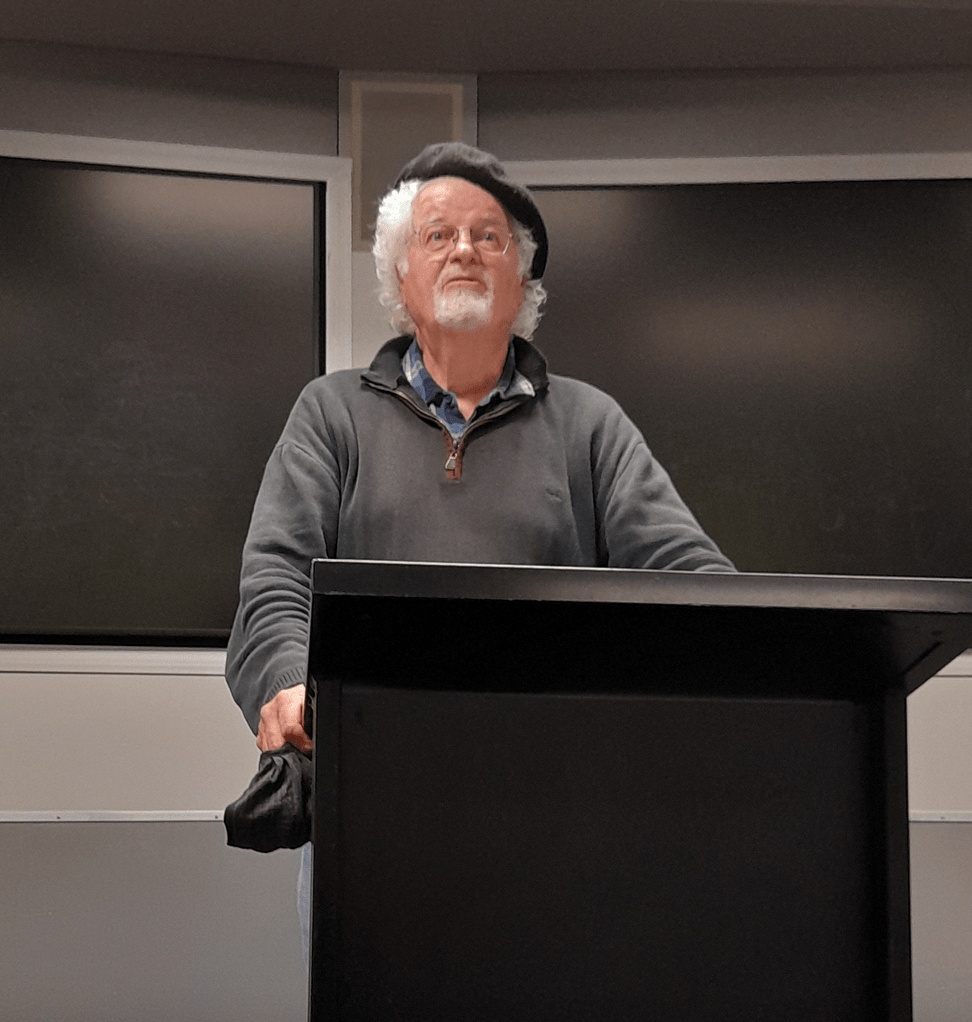

John at the launch of A Long Road Trip Home at Scorpio Books, 14 September 2023

Claire Beynon

During John’s last weeks, it became difficult for him to participate in written exchanges. I took to sending him short voice notes, recordings of nature, for instance (birdsong on a forest walk and the like) and at some point, started reading his poems back to him. These recordings I sent via FB Messenger or direct to his phone via his regular mobile number. I have recorded two favourite poems from his last collection: ‘It can be lost just when you notice it’ and ‘Breathing the Open’.

In August 2022, John sent me a screenshot of an early draft of ‘Breathing the Open’. “My remaking of a Rilke sonnet…”, his accompanying note said. He’d positioned it amongst a series of photographs he’d taken while out walking beside the estuary near his home in Heathcote. He had a special fondness for kōtare/kingfishers and kōtuku/herons. I was in Cape Town at the time. We’d been having a lengthy discussion about Barry Lopez’s last book, Horizons, each of us attempting to articulate the complicated gift of having more than one geographical home, more than one tūrangawaewae.

And here, I quote John, “It is an extraordinary time… I should have added mention of my ongoing reflections on his [Barry Lopez’s] words about imagination as that power through which a boundary is transformed into a horizon: “The boundary says ‘here and no further; the horizon says ‘welcome’”…. To be in our birthplace is to be once more held by that boundary, that holding environment; and simultaneously aware of that first horizon, our facilitating environment…”

A few ‘take-away’ instructions from John—

- Every ‘away’ is also a ‘towards’.

- Never forget that boundary that is sanctuary.

- Answer the call to venture beyond—ever further, knowing you will be welcomed

- Live simultaneously in centre and periphery.

- Wonder at Mystery

Claire Beynon reads ‘It can be lost just when you notice it’, John Allison, A Long Road Trip Home (Cold Hub Press, 2023)

Claire Beynon reads ‘Breathing the Open’, John Allison, A Long Road Trip Home (Cold Hub Press, 2023)

Jan FitzGerald

John was that rare breed. The real poet. It was in his bones. He had his own voice, found his own way, and even sitting on that edge between life and death, he made us look at things … and then look harder. He showed us how darkness could be light, sunshine could be shadow, that even “the rocks and the dead are good companions.” He worked with meditation, music, woven into the quiet dance of his words as he walked the unseen and physical world with an open heart and ready camera. John left us his final words, and in his words we find much wisdom. And “what it is just to be…”

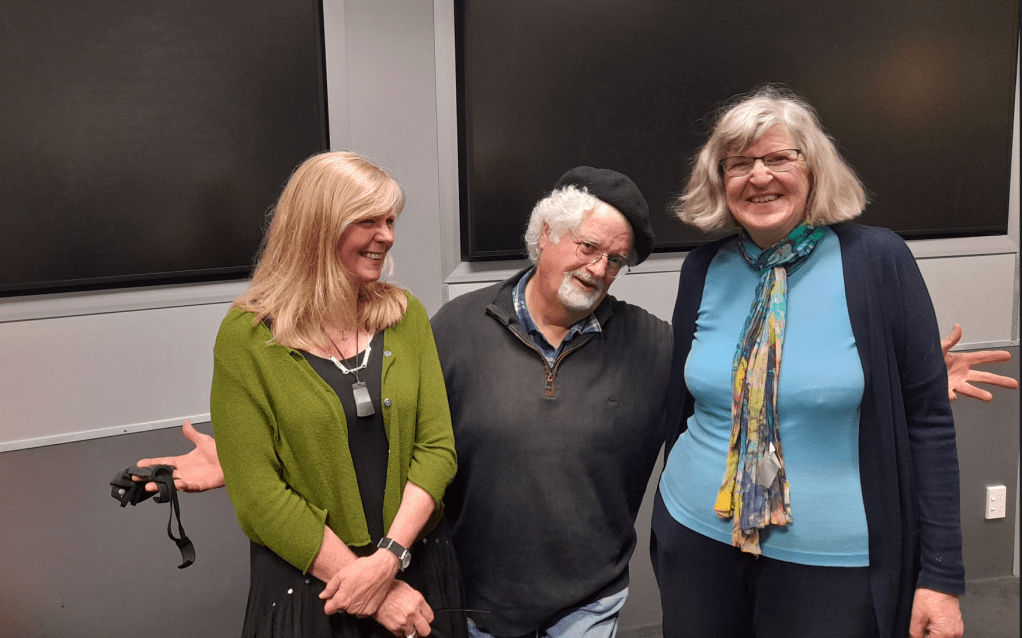

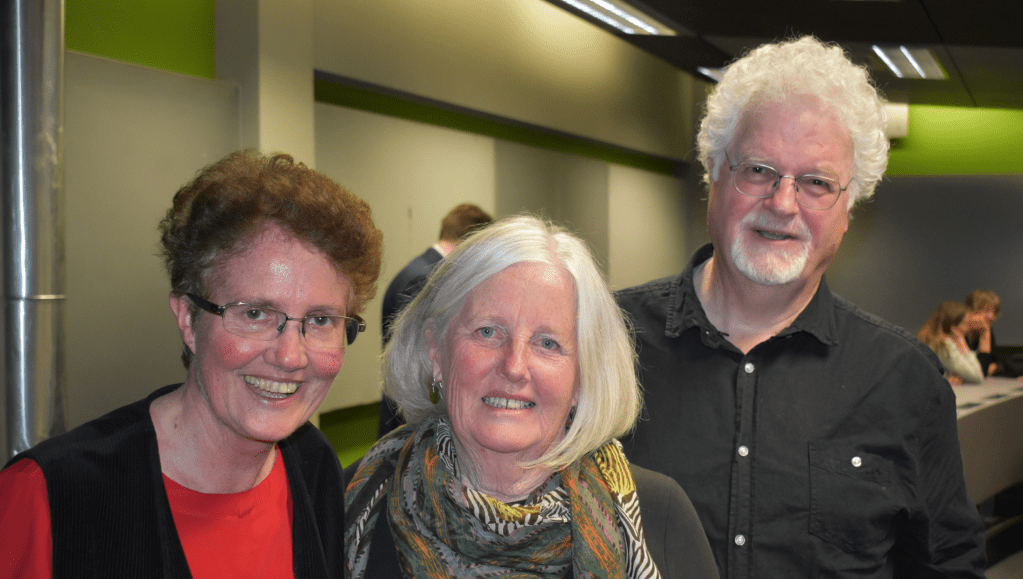

John Allison with Sandra Arnold and David Howard

Ariana Tikao

I didn’t know John Allison for long. I just moved back to Ōtautahi last June, and started attending a series of poetry events by the Canterbury Poets Collective. John was one of the people who came up to me after I first read, and complimented me on my contribution. He was really thoughtful like that.

Then, I was asked to be a guest reader at Hester Ullyart’s Common Ground Poetry events in Lyttelton late last year. John Allison and Isla Huia were the other two guest poets, and John reached out with a proposal to read some lines in his poem Mountain, River, People which I believe is about all of us sharing this land, and how we can live and work alongside one another. It was a gesture of goodwill for him to share this poem with us, and for us (Isla, me, and my cousin Karuna Thurlow) to read together. Initially when the request came through, I admit it felt ‘slightly’ like an imposition, but I am really glad that I embraced the opportunity as I know that John was sincere and deliberate in his actions, as he was with his words on the page.

The poetry event was very special, and I read some new poems I had written about the genocide that was unfolding in Gaza. John and his partner Annette – the painter referred to in the poem I have recorded of John’s ‘a woman like Syria’- came up to me after my reading, thanking me for talking about the situation in Palestine. We all had a connection over caring deeply about this kaupapa. This is one of the reasons I have chosen this poem to read in my tribute. I honour the poet and the man, John Allison, and send my thoughts of aroha to all his family and friends. E te rakatira o te toikupu, moe mai rā.

Ariana Tikao reads ‘a woman like Syria’, published online in Love in the Time of Covid: A Chronicle of a Pandemic, October 31st 2022

Joanna Preston

Joanna Preston reads ‘Why we fish’, first published in Poetry NZ Yearbook 2020, and then reprinted in Voiceprints 4 (Sudden Valley Press, 2023)

Jenna Hellar

John Allison was my poetry mentor and a very dear friend. For a while, we would meet every few weeks over coffee or a walk around the Southshore Spit and we’d talk about words, about letting a poem breathe, about what an object is really saying, what you as a poet are really saying, about line breaks and the use of ampersands and slashes, about whether to use commas at the end of a line or not, about the importance of whittling a poem by taking words away until maybe you’ve gone too far and then bringing back only a handful of the ones that are truly necessary so that the poem says something in both the words that are left and the ones that are absent. Every conversation with John was a prose poem. When we weren’t talking about poetry, we would talk about the thrill of foraging, the geology of a landscape, the grace and draw of special places, the love and trouble of humanity, the importance of looking and looking again, and again still, in order to try and understand what exactly the thing you are looking at is saying. I feel so lucky and grateful to have had John in my life and I am thankful that his words and our poetic conversations live on in me, in others, and of course, in and through his poetry.

Jenna Hellar reads ‘Epilogue’ from A Place to Return To (Cold Hub Press, 2019)

John with Claire Beynon and Catherine Fitchett, 6 October 2021

Memories of John Allison by Sandra Arnold

I first came across John in the early 1990s when he sent in a short story to Takahe, a fiction and poetry magazine David Howard and I had started a couple of years earlier. Soon after that we met him at a PEN meeting in Christchurch and he invited us and a group of other writers to his home in Lyttleton. Thus began many Lyttleton gatherings and a friendship that lasted ever since.

My husband Chris and I visited him after he’d moved to Melbourne to live in a beautiful house in the Dandenong Ranges with his wife Bettye. When we saw Bettye there she was very ill with cancer. After Bettye died John returned to Christchurch to live near his family. We saw him frequently at his house and ours as well as at book launches. What I will always remember about John is his passion for poetry, the beauty of the language he used to write it, and the many conversations we had about writing.

The last time we saw John was at his home in Heathcote Valley when he was in the last stages of cancer. He was very thin and pale, but he still had his sense of humour, his acceptance of death and his interest in writing. Just a couple of weeks later we received the phone call to tell us John had died. Even though I had been expecting this, I felt a sense of disbelief.

At his funeral the community centre was packed with John’s many friends from different areas of his art, writing, music and education life. Everyone placed a sprig of rosemary on his coffin and watched the hearse drive him away.

Sandra Arnold

Gail Ingram

Hey John,

I miss your poetry at CPC, the way

you read, the space you took.

I miss your photos of our shared skyline

and the Ōpawāho, the kōtare

watching us, the light you captured.

I feel your absence, passing your house

especially, neighbour, your wild lawn

now shaved, and all the flowers gone,

and insects too, I miss your bluster,

your large view, John, I miss

you.

Gail Ingram

John Allison with Fiona Farrell and Jane Simpson, 9 October 2019

Fiona Farrell

What do I remember of John? I remember the man I met many years ago, the very tall man in the very small cottage in Lyttelton and his great kindness when I was lost, new to the city on the university writing fellowship and separating from a long marriage. I remember John talking. He was a great talker. He knew stuff. He was a born teacher. I remember him telling me about Plutonic rock formations on the peninsula. I remember walking with John over Godley Head. He was a great walker. John playing music. John reading poems, his own and others, and his ready response to beauty, and to what was funny or absurd. John telling me about the scientists who visited the volcano that exploded from the sea off Iceland and how they went to see what would be the first life-form on this new earth, not noticing that it was themselves. I remember the grief for his sister that lay at his heart. He was a good man and a deeply serious poet.

John Allison: an appreciation

On entering John’s cottage you were immediately aware that he was a cultured man. His bookshelves were laden with poetry and interesting non-fiction titles. His musical instruments were on display and there were paintings on his walls, many by friends. I always thought John’s cottage was beautiful.

As well as being a fine poet, John was a talented musician: he played the lute and the oud. He loved the New Zealand landscape; he walked in it, photographed it and wrote about it.

John was a big bear of a man. When I visited him I was always met with a hug and a smile. He consciously adopted a positive attitude to life: he was interested in his own life and he tried to live it fully. He was an intelligent, thoughtful, decent man. He was a good man.

Nick Williamson

A poem for John

of a pale white page

for John Allison

I already miss John’s familiar tallness,

his softly spoken lilt,

that warm, glittered gaze.

I will miss his heroic improvised poems, wild – really,

dipping into a deep tundra, a vision of fire and beauty

that sang to him from somewhere else.

No more coffee collisions on banks peninsula,

sharing the mountains, the sun.

No more kind words in restaurant doorways.

But I will not miss him.

For luckily, he’s still right here

conjured in the raising

of a pale white page,

and the outline of light, or a man, walking

a silhouette through the leaves, in the wind

the hills, raining, blazing, softly, softly

at dawn, in summer, in fall,

in the shadow of dusk, and the beauty of it all.

Hester Ullyart

Hester Ullyart reads ‘Ingrid at Tyresö’ from Balance: New and Selected poems, Five Islands Press,Melbourne, 2006

Hester Ullyart reads ‘Entrances’ from Balance: New and Selected poems, Five Islands Press,Melbourne, 2006

Jenny Powell

My memories of John are those of an explorer, open to new possibilities in any dimension of experience, including the spiritual. John’s location of an essence or centre, or shard of it, was often translated and shared through his brimming creativity, but not before the final results were forged, tempered, shaped, smoothed, sung, or said.

John’s deep understanding of poetry and music allowed him entry into multiple worlds. He was fascinated by intersections and overlaps of experiences, by external and internal states of being, and by underlying poems where the sung and unsung converge. John and I collaboratively explored interpretations of music and poetry in ‘Double Jointed’ (2003). The three poems written with John are reinterpretations of music. I continue to marvel at his willingness to investigate and push beyond the usual. ‘Symphonie Fantastique’ by Berlioz, Mozart’s ‘Sonata No. 6’ and a new composition, ‘High Country Raga’, were starting points for our combined efforts. In the last stanza of ‘Playing Mozart 1’ John wrote:

He is in the room, dancing in the centre

of his melody, pirouetting allegretto

for a moment just before the final coda

then that silence afterwards, refracting …

Jenny Powell

Erik Kennedy – A poem for John and a reading

The Foraging Poem

For John Allison

John showed me

one of his private coastal foraging spots.

I felt like he should have

blindfolded me

and taken me there

in the back of a van

at three in the morning.

I am so bad

at keeping secrets.

But he was trusting like that,

knowing that, because he asked it,

I wouldn’t tell anyone—

not one of you—

where it was,

because some little pleasures

are infinite

but far more

are finite.

Erik Kennedy

I hope it’s okay if the words I contribute to the John Allison memorial post are a poem. I’ve wrestled with what to say—vacillating to and fro between personal memories and little appreciative close readings and reflections on his empathy and impact in the community—and nothing I wrote really hung together. Instead I’m turning to a different kind of language. I wrote a poem on the day of his funeral. I’m not sure it’s profound or powerful, but it does do something important, to me at least: it tries to show the way John could make you feel, the loyalty and goodwill he could conjure up. Anyway, maybe this is the place for it?

Erik Kennedy reads ‘the send-off’ from A Long Road Trip Home, Cold Hub Press, 2023

envoi

living seems more

complicated now than dying

taken off death row

and given life and then parole

some day to be

called back in to face the fact

for it’s a sentence

with a determined predicate

however I will live

as though indeed I were living

laughing it off like

anyone else with a conviction

still there are times

when it becomes quite shaky

now for instance

wanting to say the unsayable

my house of words

is creaking in the wind tonight

yet poetry is all there is

when nothing else makes sense

John Allison, from A Place To Return To, Cold Hub Press, 2019

Pingback: Poetry Shelf Weekly Newsletter | NZ Poetry Shelf