Poetry at the NAT 7pm this Wednesday, featuring Robert Sullivan and Michelle Elvy, with MC Sophia Wilson. Open mic, all welcome

Event by Jesse Mulligan RNZ Afternoons

Brothers Brewery, 5 Akiharo Street, Mt Eden, Auckland

Tuesday 21 May 2024 6:00pm – 8:30pm

Join us for a reading party! Tickets are $10 and include a drink and a spot on the couch to read in peace and spend time with like-minded readers. Arrive at 6pm, start reading whatever book you like at 7pm, then discuss with other party goers.

Tickets here

Hello

I fell out of someone’s

debut novel, and now

I don’t know what to do.

It’s scary out in the world.

I would like to wake up

in that bed again,

a morning in late

1940s sunlight, just a few

years after the war,

sharing a cigarette

with the woman

who might go on

to be my wife. I don’t know,

something must have gone

terribly wrong. I think

maybe the workshop

hated me. I didn’t even argue

or run out blindly

into city traffic. It’s just

I was never developed.

I stubbed out my cigarette

and then she dumped me.

Bill Manhire

Bill Manhire‘s last collection of poems, Wow, was published in 2020, and was a Poetry Book Society Selection. An interview subsequently appeared in PN Review. A recent collaboration with Norman Meehan and others, Bifröst, has been released by Rattle.

(…) And I let my hands tilt and the plastic

bag that you hold rustles and plumps with their

rush, I hold one back and bite into it and its

taste is the taste of the colour exactly, and this

hour precisely, and memory I expect is storing

for an afternoon far removed from here

when the warm furred almost weightlessness

of the fruit I hold might very well be a symbol

of what’s lost and we keep on wanting, which after

all is to crave the real, the branches cutting

across the sun, your standing there while I tell you,

‘Come on, you have to try one!’, and you do,

and the clamour of bees goes on above us, ‘This

will do’, both of us saying, ‘like this, being here!’

Vincent O’Sullivan, from ‘Being here’

in Further Convictions Pending, Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2009

This week I am reminded of 1968, of anti Vietnam war protests, of calls to ban the bomb, to safeguard the health of the planet, to enable all women to speak, to make choices, to be protected from abuse and subjugation, for equity across race and culture, for civil rights, for food and shelter for everyone. For love.

This week, as the bump in my recovery road feels like a steep hill, I am drawn to notions of care. I heard National Humanities Medal Recipient, Abraham Verghese in conversation with Kathryn Ryan on Radio NZ National. He lives and practices medicine in Stanford, California and is a Professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine. He will be appearing in three sessions at Auckland Writers Festival. I loved how the word ‘care’ becomes imperative both in his writing and in his care of patients and their complex narratives. His latest novel is The Covenant of Water. I loved this conversation so much I am hoping the festival produces a podcast of his session with Paula Morris. Also keen to hear a podcast of his session with kaupapa Māori academic, Leonie Pihama, co-editor of Ora: Healing Ourselves – Indigenous Knowledge, Healing and Wellbeing. That his RNZ conversation was titled ‘the joys of medicine and writing’ says it all. I am reminded of our local treasure, Eileen Merriman.

I found myself in the day stay ward this week, with the kindest nurse you can imagine, sitting on the bed after doing the routine checks, and I told her about an astonishing young woman musician and writer, Cadence Chung. How her writing is an oasis of care, how she cared so much for her peers, how she has assembled a gorgeous collaborative anthology, bringing together the work of young musicians, poets and artists. How uplifting and inspiring the book is to read and to listen to.

In my postbox this week: Tidelines by Kiri Piahana-Wong, Anahera Press, 2024

This week we are grieving the loss of Vincent O’Sullivan, paying tribute to his life as a writer, a mentor, a friend. I am reminded of the way he supported women writers, bringing women from the shadows into the light. I am especially thinking of the poetry of Ursula Bethell, and of how he supported Reimke Ensing‘s groundbreaking anthology Private Gardens (1977). I picked up this volume, reread Vincent’s ‘Afterword’, and was reminded of how wide and significant his embrace was, and how that nurturing support continued across the decades. The conclusion of his piece still resonates deeply as he addresses potential critics of women’s writing:

But that would not have been so valuable book. it would not have succeeded at what no other New Zealander has done, and that is to take women writers of many kinds, and of several generations, and presented so clearly their response to the normal realities, the usual evasions and dreams, of living as we do. We are what we are by the way that we say it.

Vincent O’Sullivan, from ‘Afterword’ in Private Gardens: An anthology of New Zealand Women Poets

Links for the daily posts

Monday: Monday Poem – ‘Oh’ by Anna Jackson

Tuesday: Review of Mythos, ed Cadence Chung

Wednesday: Review of Stones & Kisses by Peter Rawnsley

Thursday: Review and readings for Poetry NZ Yearbook 2024

Launch AUP New Poets 10

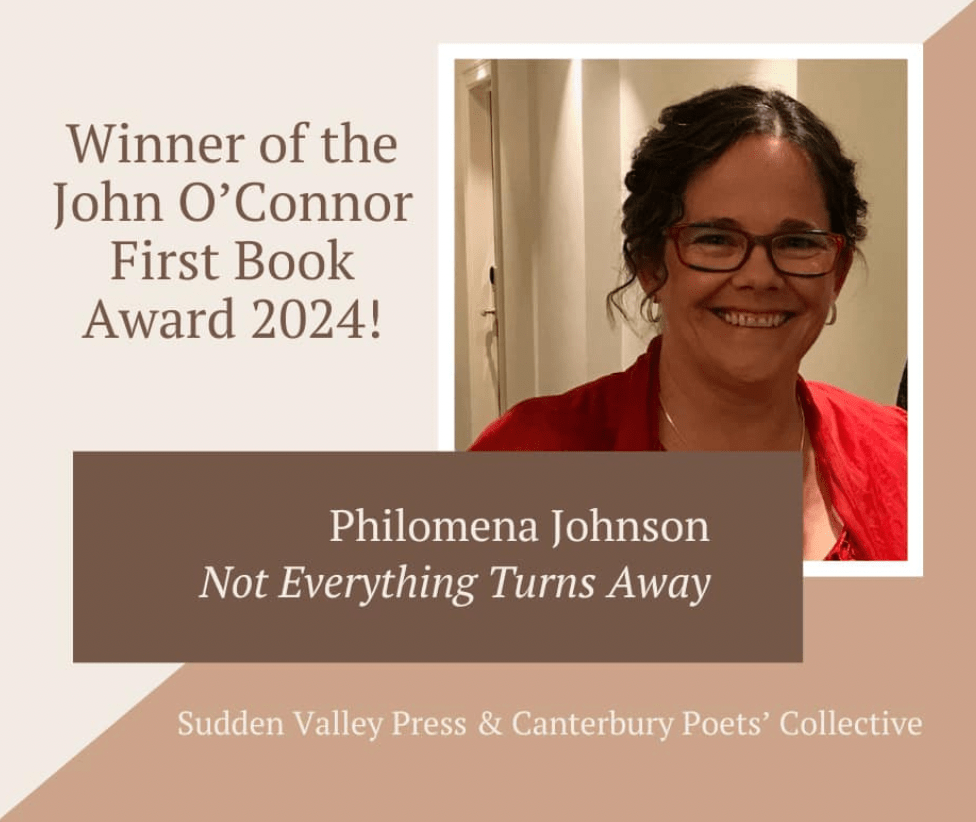

2024 winner for the John O’Connor Award for Best First Book

Friday: Poetry Shelf readings for Rose Collins

A poem

The Wife Speaks

Being a woman, I am

not more than a man nor less

but answer imperatives

of shape and growth. The bone

attests the girl with dolls,

grown up to know the moon

unwind her tides to chafe

the heart. A house designs

my day an artifact

of care to set the hands

of clocks, and hours are round

with asking eyes. Night puts

on an ear of silence where

a child may cry. I close

my books and know events

are people, and all roads

everywhere walk home

women and men, to take

history under their roofs.

I see Icarus fall

out of the sky, beside

my door, not beautiful,

envy of angels, but feathered

for a bloody death.

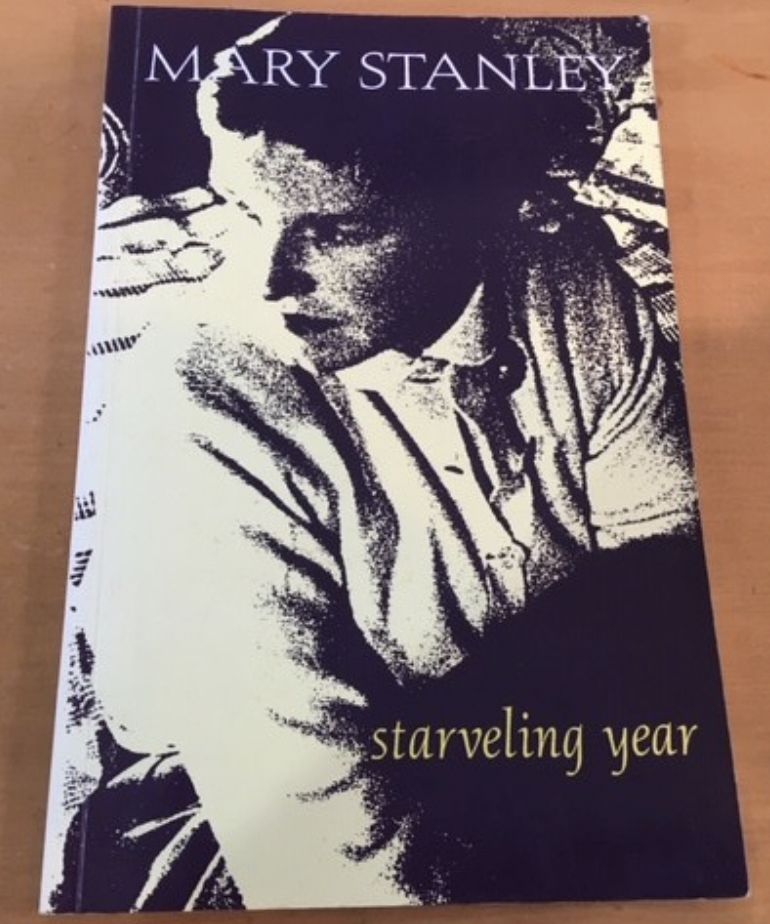

Mary Stanley

Starveling Year (Pegasus, 1953)

Also appears in Private Gardens: An anthology of New Zealand Women Poets edited by Reimke Ensing, Afterword by Vincent O’Sullivan (Caveman Press, 1977).

Mary Stanley (1919 – 1980) spent part of her childhood in Thames. Her first husband, Brian Neal, was killed in World War Two. Three of Mary’s early poems were awarded the Jessie Mackay Memorial Award (1945) and she published her work in various journals. Her second husband, poet Kendrick Smithman, wrote an introduction to the posthumous reissue of Starveling Year and Other Poems (Auckland University Press, 1994).

Mary Stanley writes out of the isolating 1950s, out of motherhood and marriage, to produce poetry imbued with love, musicality, a history of reading, personal revelations and searing gender politics. The poem, in her adroit hands, is both a weapon and a point of solace.

A musing

The look and feel of poetry books matters, not just as a marketing choice but in the aesthetic pleasure of a book as an object. Publishers, both mainstream and boutique, are giving much thought and care to the production of their poetry collections. The internal design, the paper stock, the cover, the feel of the book in the hand, these all matter. The look of the poem on the page is an active participant in the overall effect upon ear, eye, heart, mind. My only niggle is when the internal font is so small it makes reading a struggle. I have been admiring all the new books on my desk, delighting in the publishing craft of Katūīvei Contemporary Pasifika Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand (Massey University Press), the visual appeal of all the new Cuba Press poetry titles, the artisan feel of Compound Press’s the prism and the rose and the late poems by schaeffer lemalu. I especially love the fit-in-the-palm-of your-hand Town by Madeleine Slavick (The Cuba Press), the eye-catching cover on Sylvan Spring’s Killer Rack (Te Herenga Waka University Press).

Ah, I have planted a seed in my head.

Our thoughts are all of Rose this beautiful morning in Whakaraupo – next week on Bookenz we will be replaying the interview I did with Rose after she won the John O’Connor award for this poetry collection which has now been reprinted.

Morrin Rout, 3 May, 2024

To celebrate the reissue of My Thoughts are all of Swimming by Rose Collins (Sudden Valley Press), ten poets each read a poem from the collection. The new edition also has a foreword by Rose’s mother, Siobhan Collins.

James Norcliffe has written a response to the collection’s title poem.

My review posted in 2023.

A series of written tributes paid by friends and authors in 2023.

Rose Collins (1977 -2023), born in New Zealand and of Irish descent, was a poet and short fiction writer. She worked as a human rights lawyer before completing the MA in Creative Writing at the IIML in 2010. She won the 2022 John O’Connor Award and the 2020 Micro Madness Competition, and has been shortlisted for the UK Bare Fiction Prize (2016), the Bridport Prize (2020) and the takahē Monica Taylor Poetry Prize (2020). Rose was the 2018 Writer in Residence at Hagley College. She was a some-time litigation lawyer, a beekeeper and a mother of two. She lived in Te Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour with her family.

Sudden Valley Press page

The readings

James Norcliffe reads ‘My thoughts are all of swimming’

Siobhan Collins reads ‘The Port Hills hare considers rock fall risk’

Morrin Rout reads ‘Over the Fields from Ballyturin’

Zoë Meager reads ‘The weeping of the women and children is a lamentable scene’

Lynn Davidson reads ‘Everything that we are afraid of’

Frankie McMillan reads ‘She hoped that Jack would come up the stairs and hold her.’

Síle Mannion, Síle Ní Mainnín reads ‘The Squid and the Whale Send Alan a Piece of Ambergris’ in Irish / Gaeilge and in English

Joanna Preston reads ‘Telling the Bees’

David Gregory reads ‘Five Eggs’

Jeni Curtis

Jeni Curtis reads ‘Brace Comb’

The readers

James Norcliffe is an award-winning writer of poetry and fiction and an editor. His eleventh collection of poetry Letter to ‘Oumuamua was published this year by Otago University Press. He has also written novels for young people and his novel for adults. In 2022 he was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement for Poetry and tin 2023 was awarded the Margaret Mahy Medal.

Siobhan Collins lives on the Lyttelton Harbour where she practices as a Jungian Psychoanalyst in between snatching moments to write poetry. She is a graduate of the Hagley Writers Institute and is a busy grandmother to seven grandchildren. She chose this poem of Rose’s as both she and Rose lived in the aftermath of the Christchurch earthquakes and she is appreciative particularly in this poem of Rose’s wit and clever juxtaposition of poet and hare, the hare speaking for the poet and the poet for the hare.

Morrin Rout has spent 30 years organising literary events and festivals and producing and presenting book programmes on national and local radio. She is the former Director of the Hagley Writers Institute and has just retired from the WORD festival trust board.

Zoë Meager’s work has appeared in Cheap Pop, Ellipsis Zine, Granta, Hue and Cry, Landfall, Lost Balloon, Mascara Literary Review, Mayhem, Meniscus, North & South, Overland, Splonk, and Turbine | Kapohau, among others. She’s a 2024 Sargeson Fellow.

Lynn Davidson’s memoir Do you still have time for chaos? was published by Te Herenga Waka University Press, Wellington, in 2024. Her latest poetry collection Islander was published by Shearsman Books, Bristol, and Te Herenga Waka University Press in 2019.

Frankie McMillan is a poet and short fiction writer. Her poems have been selected for Ōrongohau / Best New Zealand Poems 2012, 2015 and 2022. In 2009 she won first prize in the New Zealand Poetry Society International Poetry Competition. In 2023 she was short listed for the international Bridport Poetry Prize. Her latest book, ‘ The Wandering Nature of Us Girls,’ was published by CUP Press in 2022.

Síle Mannion is a proud Irish woman/Bean na hEireann, and citizen/tauiwi, of Aotearoa/New Zealand. Published variously and widely, on this side of the world and the other, she reads everything and writes anything; poems and bits and pieces of small fictions, short stories, songs, essays and the odd odd review.

Joanna Preston is a Tasmanaut poet, editor and creative writing tutor. Her second collection, tumble (OUP, 2021), won the Mary and Peter Biggs Prize at the 2022 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. She teaches at Hagley Writers’ Institute, runs The Poetry Class, and stares guiltily out at her overgrown garden in semi-rural Canterbury.

David Gregory is an established New Zealand poet with three books to his credit and a fourth on the way. His poetry has appeared in many NZ publications and a number of anthologies. David is a founder member of the Canterbury Poets Collective and the manager for Sudden Valley Press.

Jeni Curtis is a Christchurch/ Ōtautahi writer with short stories and poetry published in various publications in New Zealand and overseas, including literary journals and anthologies. Her poem “come autumn” was shortlisted for the Pushcart Prize 2020. She was chair of the takahē trust and co-editor for poetry from 2017-2021. She was co-winner of the Heritage New Zealand poetry award 2021, and runner up in the Canterbury Poets’ Collective John O’Connor Award, 2022. Her collection of poems stone men was published in August 2023 by Sudden Valley Press and she is now an editor at Sudden Valley Press.

Poetry Shelf congratulates Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook editor Tracey Slaughter who is the 2024 Calibre Essay Prize winner. Congratulations also to contributor, essa may ranapiri, who has been selected, along with Jenni Fagan, as the inaugural Island to Island Residency residents, courtesy of Moniack Mhor, Scotland and VERB Wellington.

she takes the bark and dyes it

into the strands

a feather plucked from a sacred

bird to replace a shell

hinged by turmeric lengths

reshaping the metaphor and

moving it into a forest I’ve never been to

but want to go

essa may ranapiri, from ‘love as a verb’

The readings

Anuja Mitra

Anuja reads ‘Reprise’

Anuja Mitra lives in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. As well as Poetry Aotearoa, her poetry has been published in places liketakahē, Tarot, Turbine | Kapohau, Landfall, and international journals. She is currently trying to write more prose and feeling anxious about it. Her Twitter and linktree can be found @anuja_m9.

Tunmise Adebowale

Tunmise reads ‘A Little Grace’

Tunmise Adebowale is a Nigerian-born New Zealander currently studying at the University of Otago. She is the winner of the 2023 Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook Student competition in the Year 13 category, and the 2023 Sargeson Short Story Award for the Secondary Schools Division. Her work has been published in takahē magazine, Pantograph Punch, Turbine-Kapohau, Newsroom, NZ Poetry Shelf and Verb Wellington. She was also featured in Canadian theatre company, Theatrefolk’s 2021 collection: BIPOC Voices and Perspectives Monologue. You can find her on Substack

Charles Ross

Charles reads ‘Hilaroroa’

Charles Ross is a year 13 student who lives next to a tidal estuary in Waitāti, just outside Ōtepoti Dunedin. Charles’s poems ‘Hikaroroa’ won first prize in the 2023 Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook student poetry competition in the year 12 category.

Adrienne Jansen

Adrienne reads ‘Five am among the pine trees’

Adrienne Jansen writes fiction and non-fiction for adults and children, but poetry is at the heart of it all. For her poems are often like photographs, recording a small moment, like this poem. She has published four collections of poetry, and is part of Landing Press, a small Wellington publisher of accessible poetry that particularly includes voices not often heard. She lives in Tītahi Bay, north of Wellington.

essa may ranapiri

essa reads ‘love as a verb’

essa may ranapiri (Ngaati Raukawa, Te Arawa, Ngaati Puukeko, Clan Gunn, Horwood) is a person who lives on Ngaati Wairere whenua. Author of ransack and ECHIDNA. PhD student looking at how poetry by taangata takataapui enhances our understanding of atuatanga. Co-editor of Kupu Toi Takataapui | Takataapui Literary Journal with Michelle Rahurahu. They have a great love for language, LAND BACK and hot chips. Thanks as always goes to their ancestors, who are everything. They will write until they’re dead.

Shaun Stockley

Shaun reads ‘Autumn (onset)

A museum storyteller by day, Shaun Stockley draws on a lifetime of poetic ambition to explore the stillness and beauty of our everyday world. First published in Young Writers (UK, 2004), his recent works have appeared in the Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook(2023, 2024) and the Given Words Poetry Competition (2023). He has also contributed several war poems to the National Army Museum Te Mata Toa in Waiouru.

Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor

Aimee-Jane reads ‘Gorse’

Aimee-Jane Anderson-O’Connor is a Kirikiriroa writer, collage maker and dabbler. She believes in the power of community, collaboration, and imagination.

Medb Charlton

Medb reads ‘Wairēinga /Bridal Veil Falls’

Medb Charleton is originally from Ireland. Her poetry has been published in journals in Aotearoa New Zealand including Landfall, Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook, Sport and Turbine|Kapohau.

The review

Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook 24 is again edited by Tracey Slaughter. It features poetry by Carin Smeaton, reviews of 29 books, includes two essays (one by Erena Shingade and one by John Geraets) and 123 new poems. You’d be hard pressed to find greater review attention paid to local poetry books from a range of reviewers.

Tracey’s introduction is the perfect introduction to a selection of poetry that is eclectic, acidic, honeyed. She discusses the first poem she ever wrote, aged twelve, in a house and with a patriarch she loathed. Her internal wounds flooded into the lines, sparking, fierce, non-deferential, and it seems that this first poem propelled her into the complicated, necessary and wonderful currents of writing. She is placing the personal before us, inviting us to reassess what a poem ought to be, and whether navigating the dark, the pain, or personal trauma is to be dismissed, or whether various forms of bleeding on the page can be vital facets of poetry, avenues into ‘feeling deeply’, for both reader and writer. She makes poignant reference to the loss of Paula Harris and Schaeffer Lemalu. For all kinds of reasons, I found the introduction a source of light, a reason to pick up my pen, to open another book, to let ideas simmer.

Tracy writes:

And reading this year’s poems, I felt that weight, that toll. If the imagery of end-days was ever-present, so too was the echo of how much our poets pay to speak for it. It can be a tough haul from our first poem to our last one, and after long-term exposure to the system we are so often eroded into poetry, hollowed, ground-down, exhausted into it – poem after poem that came in this year sounded voiced from the “end of the rope”, uttered “right up against this precipice”, hanging on by a “whimper blight a slow sapping”, a statement of precarity, struggling to preserve in the lines the frailest shred of hope.’ from ‘Writing from the red house’

night fell and never got up

so many floors of sediments ago

the sun forgot all signposts

as the rainbow sank past the last bar

of reception, nightshade

photons relinquishing blue.

Megan Kitching, from ‘In the Midnight Zone’

Tracey’s introduction was especially apt as I struggle with what to post on Poetry Shelf – as the toxic and difficult world collides with the way poetry offers delight, writing it, reviewing it, reading it. New blog ideas simmer in the middle of the night and I keep returning to the idea that Poetry Shelf is a meeting place, a way to exchange ideas and poetic forms, new directions and old enchantments.

I betake myself to my mattress, fold my

t-shirts in neat little rows. Dream of different

houses, of black cattle running below my

levitating body. Tend to get so submerged in

my own despair, an exponentially multiplying

occupying force. The rain has bought the

vermiform of my guts to the mud-slicked surface.

Elliot McKenzie, from ‘Small heights’

Poetry Aotearoa Yearbook 24 is both sharp edges and warm embrace. It is curve and skid and sinkhole. It is open window and bleeding wound. It is echoing motifs and themes, shifting tenor of voice, variable forms. Enter this poetic thicket and you will fall upon: clouds origami hallucinations rose-bushes illness birds light ghosts death streams kitchens angels coffee vanishing points the weather whanau love supermarkets hospitals the moon the sun a first kiss time-passing.

Carin Smeaton, the featured poet, brings voice into sharp searing brilliant focus, with shifting voices, with everyday vernacular, with conversational pepperiness. You are in the embrace of whanau, the land, experience, life and death, tough circumstances, the after and ongoing effects of a pandemic, a cyclone. In an interview with Tracey, Carin acknowledges Tracey’s characters and narratives have inspired her ‘to write more from the fire in my belly’. Carin writes for herself, from herself, to weave the damaged, the difficult, the challenging out into the open space of her poems. She also, importantly, writes within and because of communities: aunties, friends, wāhine, poets, especially Māori poets.

You will find other writers in the shadows of the 123 poems: Mary Oliver Paula Harris Gregory Khan Dylan Thomas Michel Foucault TS Eliot Eleanor Catton. You will find an eclectic range of poets, from Adrienne Jansen, James Norcliffe, Kerrin P Sharpe, Erik Kennedy, Jan FitzGerald, Anuja Mitra, Aimee-Jane Anderson O’Connor, Riemke Ensing and Elizabeth Morton to alana hooton, Alice Hooton, Amanda Joshua, Devon Webb, Keith Nunes and to the winners of the Secondary School Poetry Competition.

Tracey Slaughter with Carin Smeaton at launch

and I run run run run run run run run through every movie scene

where one of the main characters has realised they can’t live without

your love and they’re about to miss their last possible chance to tell you that and to be happy and so we all, all of us movie characters, all of

us afraid to be loveless for the rest of our lives, all of us afraid we’re

about to miss our one chance, we run run run run run

Paula Harris, from ‘If you have ever had a delayed flight …’

The poems might get you in the gut or heart or stomach, perhaps even your bones. The issue is entitled revelations, a fitting title for a gathering that gets you musing on what poetry can do, on the connections it might forge, the experiences it can negotiate, and yes, the wound and the stitching, the pain and the hope. Find your own pathways through this engaging thicket.

Tracey Slaughter teaches creative writing at the University of Waikato, where she edits the journals Mayhem and Poetry New Zealand Yearbook.

Massey University Press page

Auckland University Press and Unity Books Wellington invite you to celebrate the launch of AUP New Poets 10, featuring Tessa Keenan, romesh dissanayake and Sadie Lawrence.

***

6pm

Wednesday, 29 May 2024

Unity Books Wellington

57 Willis Street

Wellington

***

Thanks to the Unity Books for hosting and bookselling on the night!

The 2024 winner for the John O’Connor Award for Best First Book is Philomena Johnson. Congratulations Mena!

Judge Harry Ricketts describes it as “an extremely resonant, well-turned collection, quick with observation and insight… These are poems which will make you pause and reflect as you read, and will continue to work on you long after you’ve closed the book.”

The Sudden Valley Press John O’Connor Best First Book Award is awarded to a Te Waipounamu South Island resident poet who has not previously published a full-length collection of poetry. Johnson’s collection will be published on National Poetry Day, 23 August 2024.

PHILOMENA JOHNSON graduated from The Hagley Writers’ Institute in 2017, where her portfolio was short-listed for the Margaret Mahy Award. Her poetry has appeared in The Quick Brown Dog, The London Grip, takahē, Fuego, a fine line, and in the anthologies broken lines / in charcoal and Voiceprints 4. Philomena tutors at WRITE ON: School for Young Writers.

Stones and Kisses, Peter Rawnsley, The Cuba Press, 2024

Waiting

Let a room wait

and sing with emptiness.

Let windows look in to touch

the stillness with sky light

and distant sounds of a city.

Let a table wait to be set

and candles to lift their spearheads.

Let a cup wait for wine and

bread wait to be broken, shared.

Let chairs wait for those who wait

and words rise from waiting pages

to speak in the mouths of proclaimers.

Let the air hold its breath and wait

for song and exaltation.

Peter Rawnsley

Picking up a poetry collection by a poet new to me, I always feel like I have an open-ended train ticket, not sure what I am going to view on my travels, where I will travel, what conversations will percolate as I read. Stones & Kisses is Peter Rawnlsey’s second collection, but this is my first sojourn with his work. The writing is melodic, contemplative, detail rich. He can move from a degree of mystery (what is behind the door?) to gentleness (the blessings to loved ones) to eclectic travel at home and abroad. He moves from reverie and contemplation to the rescue of a soldier in the desert to a first date. He can evoke a scene, a state of mind, a situation with deft and melodic use of language.

There are overlapping themes and motifs but the collection as a whole is infused with nature and with love. When I say ‘nature’, I am thinking of flora and fauna, especially birds, godwits, sea eagles, gulls, pied shags, tūī. But I am also thinking of human nature, where the contemplation of the ‘subdued slap and seethe / of a quiet sea’ or how ‘[t]he disturbed flight of gulls / knits together shore, sea and sky’, might also represent, across the collection as a whole, a contemplation of self. There is grief and death, the pain of loss, and there is love, there is ‘I’, ‘you’ and ‘she’. Love is there in the passing of time, as memory, as photograph, as presence. Love in ‘I’ and ‘you’ and ‘she’.

Reading the collection, I am reminded that poetry, like some art, is a form of transcendence. And indeed, there are several poems where the speaker stands absorbed before an artwork:

Scatter on the water’s surface.

Become the canvas’s painted surface.

hide within yourself a secret waviness.

Be filled with an inpouring of light.

from ‘ At the Monet exhibition’

I am particularly drawn to the list poems, to the enchanting and entrancing effect of repetition. One poem begins, ‘The word spoken is tree‘, and then builds a portrait through eclectic and poetic detail. You become embedded in the scene.

Attentiveness to the world versus immunity to the world is infectious. The way, despite its toxic canvas, we can lean into the world sideways, lean slantwise into a poem, into what is there before us and gain nourishment is imperative. Resist immunity. The opening lines of the opening poem of this terrific collection resound until the final page. Stones & Kisses is a delight.

Today I am a different me than I was yesterday.

I can feel it in how I hold myself and look about.

Something has changed, everything leans a little sideways.

from ‘ Leaning sideways’

Peter Rawnsley is a retired public servant living in Porirua, New Zealand. Stones & Kisses is his second collection of poems, following Light Cones (Mākaro Press, 2018).

The Cuba Press page