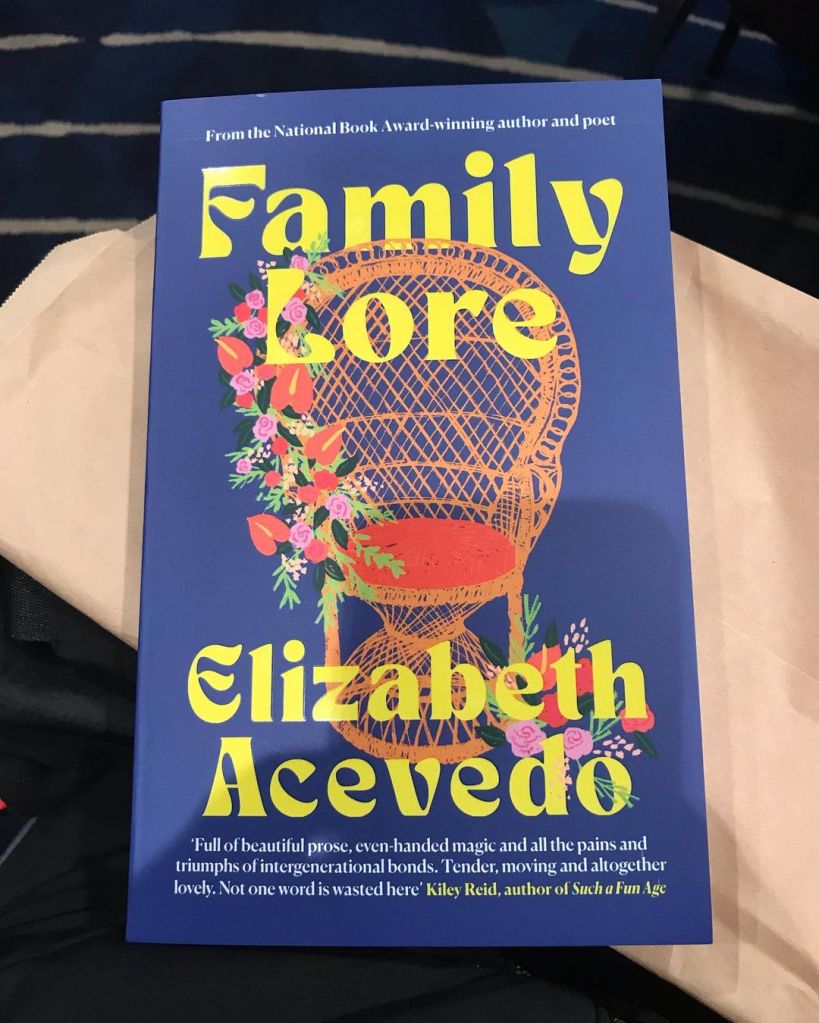

Editors Mere Taito, David Eggleton and Vaughan Rapatahana

Katūīvei Contemporary Pasifika Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand

cover art: Dagmar Vaikalafi Dyck ‘a gift of thanks’

Massey University Press, 2024

Violet puts down the paperback.

Those stories have been imprinted over the veins in her wrist.

Over and over.

Again and again.

So much has been written over the margins of her stories.

She can no longer read her own writing.

The blue ink against caramel wrists,

smear into the waves that lapped against the shores of her homeland,

the waves that battered the boat across the South Pacific.

Waves goodbye.

Ruby Rae Lupe Ah-Wai Macomber from ‘Storytelling’

Thank you to the poets who made audios, and to the editors, Mere, Vaughan and David, who have answered a few questions with both heart and care – you have made this post special. So moving. So very moving. I imagined being able to listen to an audio book, as I often do with a poetry collection or anthology I love so much. Thank you.

Many peoples of the Pasifika diaspora now live in Aotearoa, multiple generations that have come from multiple departure points. The editors of a new anthology of Pasifika poetry, David Eggleton, Vaughan Rapatahana and Mere Taito, have assembled a vital and magnificent weave of voices. Katūīvei is lovingly produced in a hardback version by Massey University Press. In their introduction, the editors write: ‘Pasifika peoples represent almost 10 percent of the population, are one of the fastest growing demographic groups in the country, and contribute profoundly to New Zealand society in all kinds of ways, including through a vibrant efflorescence of cultural activity, from music and dance to art, theatre, film and literature.’

The editors acknowledge poets who have paved the way – with publications, performance spaces, mentoring, teaching. From the first Pasifika poet to be published here, Alistair te Ariki Campbell, with his Mine Eyes Dazzle (Pegasus Press, 1950) to Albert Wendt whose writings, poetry, teachings and mentorship have been a touchstone for generations, to Grace Iwashito-Taylor, Daren Kamali and Ramon Narayan forming the South Auckland Poetry Collective, to Selina Tusitala Marsh who has inspired new generations of poets through her own writing, performances, teachings and honours, to Doug Poole’s Blackmail Press, to anthologies edited by Albert, Reina Whaitiri and Robert Sullivan. To the ongoing wave of poets who, with new books published, slam, spoken word and festival appearances, enrich our writing communities. As David Eggleton writes: ‘By the beginning of the second decade of the millennium, Pasifika poetry had undeniably become a major presence in New Zealand literature, helping to illuminate our understanding of Aotearoa New Zealand and its place in the world on a number of levels and in a variety of ways.’

‘Katūīvei’ is a hybrid term, especially coined for the occasion, bringing together ‘kavei’ – meaning navigate, and the double voice box of the ‘tūī’. A perfect word for a collection of writing that is an act of ‘wayfinding’ between cultural spaces and creative discoveries. Katūīvei is an anthology of multiple forms, melodies, subject matter, visual images, epiphanies, confessions, challenges, grief, wounds, healing, but there is a connecting current, a deep and shared love of words, of poetry, kinship, self navigation.

As I read, I am gathering words like talismans, as steeping stones, like echoes that connect and enhance and draw me in deeper, deep into the richness of this sublime meeting place.

I am moving with the political

Emalani Case navigates ‘On Being Indigenous in a Global Pandemic’, and challenges the mantra that ‘we’re all in this together’, calling this, ‘But in a global pandemic / being indigenous means / writing, / speaking, / crying, / and protesting // your people into existence’.

. . . to the personal

In ‘Straightening Out’, Luke Leleiga Lim-Cowley navigates homophobia though a tangle of hair – ‘Our hair is poetry. / Don’t forget this. / Even when / words land in you like wounds / There’s a poem here / So I write this to you’.

. . . to names and naming

such wounds, such vital pathways into how names and naming matters, from the searing brilliance of Selina Tusitala Marsh to Denise Carter, Aziembry Aolani, Aigagalefili ‘Fili’ Fepulea’-Tapua’i, Serie Barford.

. . . to family

the anthology is infused with family, giving presence to mothers fathers brothers sisters cousins genealogies kinship. Listen to Schaeffer Lemalu‘s breathtaking ‘im’:

i guess a lot of younger people

are discovering their pasts

and what it means for their future

thats beautiful

i feel stuck in the blotchy pigments

of michael jacksons face

unsure of who i am now that i

im who i always was

to begin with

just me

a constantly evolving entity

Schaeffer Lemalu, from ‘im’

. . . to body

I am splintered splattered recast by Serie Barford‘s ‘Into the world of light’ and its ripples of wounded heart – ‘I resolutely lanced my heart / a swollen fist about to burst / with a shark tooth plucked from a dream // poured honey into the first chamber // soothed gnawed memories / sent them west with wild bees’.

. . . to the compounding questions

What is your name? Where are you from? What do you speak? Who are you? Where are you from? I am thinking of Tusiata Avia‘s ‘We are the diasporas’ and Audrey Brown-Pereira‘s ‘who are you, where you come from, / where have you been your ()hole life’. For a start.

. . . and to love and loving

whether it is the love of home and place in Daren Kamali‘s ‘Duna does Otara’ or Grace Iwashita-Taylor‘s ‘Dear South Auckland’, or Lana Te Rore‘s ‘A Letter to a Younger Self’, or Karlo Mila‘s loving ode to Albert Wendt:

You’ve traversed it all,

charting outsider territory

with black star

after black star,

before us.

The relief of

another way of mapping.

Karlo Mila, from ‘After Reading Ancestry’, for Albert Wendt

Katūīvei is an extraordinary weave of experience, ideas, issues, challenges, recognitions, community. It is a book to travel with, to hold to your heart, to talk about, to set you in search of collections by individual poets, to savour the familiar, and to set sail with the new. Every time I open the anthology, I discover a new reward. This book is a labour of infinite love, by the editors, by the publisher, by the contributors, and now it is over to us as readers, to navigate, to map, to imagine and to realise how good our place, in all its awe-inspiring and humane dimensions, can be.

Looking at rain too long has given me eternity.

A mirror cut away from my country and sea.

I lived in a fruit that fell from a child’s hand,

now I cry when the moon is in my dream.

I was made out of wood and my heart

was full of saltwater; chasing a shadow from

my body led me to this secluded room,

here I watch the horizon be a photograph

John Pule, from ‘Looking at rain too long has given me eternity’

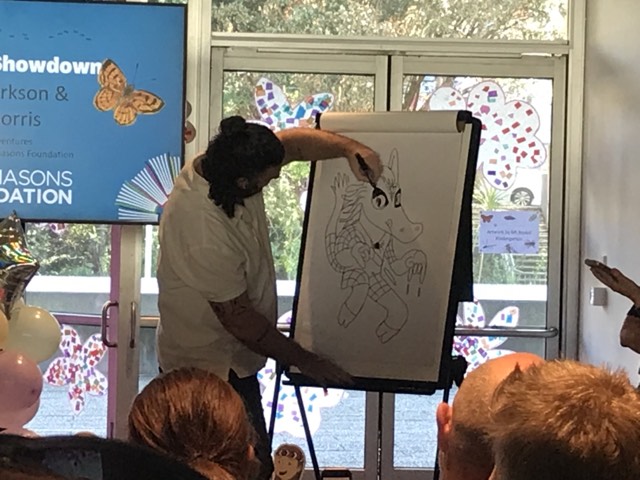

Launch at the Newtown library

Karlo Mila

The readings

Daren Kamali

Photo by Julia Mageau Gray

Daren reads ‘Duna Does Otara’

Daren “dk” Kamali – poet and multidisciplinary artist based in Aotearoa. Wrote this poem “Duna Does Otara”, while studying a Bachelors Degree in Creative Arts at MIT, Otara in 2011, also featured in Landfall Journal under South Auckland.

Working on my next collection of poems “I’m Not Your Coconut” inspired by James Baldwin. Also indulging in a research-revival-art, a touring exhibition and series of self published books known as the “Ulumate Project: Sacredness of Human Hair” since 2013 with a collective known as Na Tolu.

Emalani Case

Emalani reads ‘On Being Indigenous’

Emalani Case is a Kanaka Maoli writer, teacher, and aloha ʻāina deeply engaged in issues of Indigenous rights and representation, colonialism and decolonisation, and environmental and social justice. She is the author of Everything Ancient Was Once New: Indigenous Persistence from Hawaiʻi to Kahiki (2021). She is from Waimea, Hawaiʻi.

Joshua Toumu’a

Joshua reads ‘Veitongo’

Joshua Toumu’a is an 18 year old poet of Tongan, Papua New Guinean and Pākehā descent studying at Te Herenga Waka. He was the winner of the Schools Poetry Award in 2022, and a finalist in the Katherine Mansfield Short Story Competition in 2023. His work has also been published in Starling and The Friday Poem.

Serie Barford

Serie reads ‘Into the world of light’

Serie Barford was born in Aotearoa to a German-Samoan mother (Lotofaga) and a Pālagi father. She was the recipient of a 2018 Pasifika Residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre. Serie performed from her collections at the 2019 Arsenal Book Festival in Kyiv, where the Ukrainian translation of Tapa Talk was launched. In 2021 Serie collaborated with film-maker Anna Marbrook for the ‘Different Out Loud Poetry Project. Her most recent collection, Sleeping With Stones,was shortlisted for the 2022 Ockham NZ Book Awards. In 2022 she collaborated with Dutch artist Dorine Van Meel, whose video and performance piece, ‘Silent Echoes’, was exhibited in various European cities to address colonial practices and climate crisis through poetic contributions.

Amber Esau

Amber reads ‘Liminal’

Amber Esau is a Sā-Māo-Rish (Ngāpuhi / Manase) writer of things from Tāmaki Makaurau. She is a poet, storyteller, and professional bots. She is co-editor of Queer Poetry Anthology, Spoiled Fruit (Āporo Press, 2023). Always vibing at a languid pace, her work has been published both in print and online including in Puna Wai Korero, Rapture, Te Awa o Kupu, Skinny Dip! and Annual, NZ poetry Shelf, Ora nui, Poetry New Zealand Yearbook and Going West Poetry Videos. She is a recipient of the emerging Pasifika writer’s residency from the Michael King Writers Centre and the ideas in residence residency from the Basement Theatre.

Tulia Thompson

Tulia reads ‘The Girl That Grew into a Tree’

Tulia Thompson is of Fijian (Rukua village from Beqa), Tongan, and Pākehā descent. She has a Master’s degree in Creative Writing from Auckland University and a PhD in Sociology. Her book Josefa and the Vu, a fantasy adventure for 8-12 year olds was published by Huia in 2007. She writes poetry and essays.

A conversation with the editors

Paula: What were the key joys in assembling this special anthology? The challenges? The surprises?

Mere: A high was discovering poets who were writing outside the scrutinising glare of the literary establishment. I am referring to poets (and there are many of them in Aotearoa!) like Maureen Fepuleai, and Faalavaau Helen Tau’au Filisi who take on print publication projects on their own without the involvement of presses like AUP, and OUP, or poets who write/perform/publish on social media. I thought of Janis Freegard’s research during the reading phase of Katūīvei and I wondered if our narrative of ‘publication’ was really a story of deficit especially if we consider other ways in which Pasifika poets are ‘publishing’. Another joy, was finding poets who have incredible range of voice like Cook Island writer Rob Hack. He can be belly-aching funny and deathly serious in his work. Buy his collection Everything is Here. Finding contacts of a few poets was a challenge but we were determined and treated this almost like an operation by sharing networks and leads. Surprises? – the volume of Pasifika poetry produced in the last 10 years! On that note, a big vinaka vaka levu to Massey University Press for taking on this project!

Vaughan: There were many joys, among them discovering and exploring the sheer range of topoi, the diverse range of approaches to writing a poem – the styles – as displayed, for example, by the intricacy of the work of Pelenakeke Brown, and the pleasure I found in the work of poets whom I did not earlier know much about, such as Rob Hack and his fine toikupu. Indeed, his work was a surprise and brought home firmly for me the fact that there are many very gifted Pasifika poets residing in Aotearoa. Younger poets such as Rhegan Tu‘akoi, who are the next generation of Oceanic poetasters. More awe!

Another joy was the fact that we three editors were able to locate and include a wide range of poets from young, new, exciting talents, to poets with little if any publishing record, to the esteemed founts of Pasifika poetry within Aotearoa New Zealand, such as David Eggleton himself, Tusiata Avia, Albert Wendt, Selina Tusitala Marsh, Serie Barford, Karlo Mila, Courtney Sina Meredith, John Pule, Daren Kamali, Grace Iwashita-Taylor, Simone Kaho, Leilani Tamu, among several others – indeed that list is lengthy!

Challenges? The only wero I faced was ensuring we could include as many gifted poets as possible in Katūīvei, especially after we continued to discover more and more of them.

David: The aim in putting Katūīvei together was to celebrate the intertwining currents of Pasifika poetry connecting Aotearoa to the peoples of the Pasifika diasporic migrations and their descendants. We knew there had been a lot of Pasifika poetry published in the past decade, with important collections from Selina Tusitala Marsh, John Puhiatau Pule, Leilani Tamu, Tusiata Avia, Simone Kaho, Daren Kamali, Karlo Mila, Courtney Sina Meredith and others, but between us we uncovered a great flowering of very recent poetry that we felt it important to acknowledge as transformative in novel and exciting ways. We wanted to showcase these poems not only as a form of truth-telling about the diasporic experience, but we also wanted to show how various Pasifika innovations — the cross-overs, blendings and provocative fusions, with the English language as the common denominator — are helping to re-energise and re-direct New Zealand’s poetry traditions at this point in the nation’s cultural narrative.

Paula: Did you discover things about yourself as a poet? About writing, reading, who you are?

Mere: My practice was already shifting when we started work on Katūīvei. I have been working with archival texts in my doctoral research and responding in kind with multilingual visual poetry via digital platforms so during the reading for Katūīvei, I found myself drawn to collections and writing that experiment with visual forms such as typeface, spacing, text arrangement, and graphics. Pelenakeke Brown’s work and Selina Tusitala Marsh’s graphic poem ‘Ransom’ in Dark Sparring are form-focused and visual examples. Writers who are bilingual also got my attention. It is wonderful to see other languages on the page other than English. I also discovered that I am drawn to writing that brings fresh and new perspectives to familiar tropes such as atua, ancestors, vaka, sea, and identity. These new approaches got me sitting up straight. The fresher, weird and more off-centre the poems were, the more appealing and interesting they were for me.

Vaughan: I guess I was reminded that poetry, ngā toikupu, is such a wide-ranging activity and that one always must be expanding one’s own craft outwards, as to encompass as many new directions – subjects, themes, stylizations, socio-political stances – as are relevantly viable. That I have many potential vistas to visit and visions to vivify, some of them in response to and as te tautoko o Katūīvei and especially the more politicized pieces proselytizing its pages. As for example the fine first poem in this anthology, Marina Alefosio’s Raiding the Dawn and also many others such as Sala‘ivao Lastman So‘oula’s Blackbird. Indigenous peoples share so many experiences, and they are not all salutary: indeed, some have been, continue to be, and need to be confrontational.

David: Well, this is not a book about one poet. This is a book about bringing poets together and how we might do that. It is an anthology responding to poetic expressions of a sense of community identity, and what that might be. The three of us worked with talanoa, with dialogue, with protocol: to try to reach out to all the interesting poets in the Pasifika community in New Zealand. This was not easy and we did have to have some practical constraints in terms of choices to make the project feasible. We began work on this book at the beginning of lockdown, so it has been a long journey, checking and double-checking. We have not tried to force any messaging or impose any theoretical framework, but instead we responded to the richness and complexity, and tried to represent it correctly. If we have an emphasis, it is one that is specific to the Pasifika way of doing things, of seeing, listening and telling. We might talk about new work, ground-work, story-work, blood-work, heart-work: this is what the poets themselves had to do, and make it manifest. I include myself here.

What I get from this assembly of poems is a sense of diversity with an underlying unity, which comes from an implicit outsider status that most Pasifika poets have felt in the past, certainly. So, there are poems that celebrate, that remember, that investigate, that recriminate, that affirm, that argue. There are poems about rejection and poems about acceptance. There are poems that show us language’s capacity to empower, or that return to the succour and solidarity of family, or that show the conflicts and the uprooting — the wrench — associated with re-location to a place where you had to measure up to different standards. There are poems that deal directly, or else obliquely, with the pledge and promise of life in a different country, and with the baggage of old colonial hierarchies and assumptions. Two takeaways: the ocean is central and so is resistance, in myriad forms.

Paula: Like so many people in these troubling times, I keep agonising over what and how to write, what and how to blog. Your anthology is a gift. Is the local and global inhumanity affecting you as a writer, as reader?

Mere: For sure. I mean the vulnerability of my mother tongue Fäeag Rotuạm Ta brought on by the globalisation of English is a key factor in my going ‘multilingual’. I have made it a life-time mission to include at the very least, a Rotuman word in all of my works going forward. My research focuses on Indigenous texts so I have been reading writers like Natalie Harkin’s archival poetics that broadly looks at institutional trauma on Australian Aboriginal people and re-discovering and re-reading Naomi Shihab Nye’s poetry against the atrocities of the Palestinian genocide. Reading works of writers like Harkin and Nye allows me to recentre and appreciate communities and people who have been ‘occupied’ and ‘unceded’. I think of my ancestral home Rotuma and its political relationship with Fiji and how our position of dependency could turn ‘occupied’ in the hands of a problematic government. I shove this at the back of my mind and cross my literary fingers because it is too traumatic to imagine.

Vaughan: Inhumanity! Affecting me? Always has done, always will do, especially as he kaituhi Māori writing in te reo Māori against an all-too-often monotonously monolingual and monocultural backdrop. Katūīvei does make me feel better, as so much of its content is a bastion of Pasifika mana and indeed humanity, is a crucible of individuals both seeking and confirming their Pacific/Aotearoa identities, in the face of the above-mentioned majoritized backdrop both within and outside this skinny country we reside in. Accordingly, I want to continue to write as a repeller against inhumanity, wherever it may be, and not only via poetry either. *

* More especially nowadays, as I continue to combat this bloody cancer invading my body and which I am currently being zapped via radiotherapy every day for!

David: Lawrence Ferlinghetti once said ‘the state of the world calls out to poetry to save it’. However, Percy Bysshe Shelley claimed: ‘poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world’. But his friend and contemporary Thomas Love Peacock mocked him, saying poetry is: ‘minds capable of better things, running to seed in the specious indolence of these empty aimless mockeries of intellectual assertion’.

The sad truth is that history shows even ruthless authoritarians and regime tyrants virtue-signal by writing poems, and then get books of them published. In the end, poetry is the most paradoxical of art forms: it is there to provoke, but also to console; it is the music of what happens. As W.H. Auden wrote: ‘Will you wheel death anywhere in his invalid chair? … Time will say nothing but I told you so.’

Mere Taito (Malha’a, Noa’tau (Rotuma)) is a Rotuman Island scholar and creative writer (Poetry, flash fiction, short story) based in Kirikiriroa. Her creative work has been published widely in anthologies and journals such as Landfall, Bonsai, and Best New Zealand Poems. Her PhD studies at the University of Otago focuses on the contributions of Rotuman archival texts and digital technology toward the writing of visual multilingual Rotuman poetry.

Vaughan Rapatahana (Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Te Whiti) is a poet, novelist, writer and anthologist widel published across several genres in both his main languages, te reo Māori and English. He is a critic of the agencies of English language proliferation and the consequent decimation of Indigenous tongues. His most recent poetry collection, written in te reo Māori (with English language ‘translations’), is titled te pāhikahikatanga/incommensurability. It was published by Flying Islands Books in Australia in 2023. Vaughan lives in Mangakino.

David Eggleton is a poet and writer of Rotuman, Tongan and Pākehā heritage. His collection The Conch Trumpet (Otago University Press, 2015) won the 2016 Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. He also received the 2016 Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry. David was the Aotearoa New Zealand Poet Laureate from 2019 to 2021. He lives in Dunedin.