Poetry Shelf Monday Poem: The Ribbon-Maker by Madeleine Fenn

1 Reply

THE RIBBON-MAKER

Never was there a human hand that resisted the tug of ribbons,

the pastel urge to pull it all apart. The prettiness of a bow

is so much in the unravelling.

Many stitches ago, when I was a small boy,

bound to the chime of church bells, I dreamt of becoming a ribbon maker.

Silks, satins, patterns of organdies, the weave of sweet fibre.

Little else in life is so purely decorative, and even less so full of order.

I dedicated my life to the making of ribbons, in the old manner.

I strove beyond what most mortal men do. I made it my business

to tie things up and make them better, to stave off the darkness by means

of material light. How my ribbons shone in shop windows,

or strapped about the ankles of ballerinas!

Crisscrossed on the back of a corset, zigzagged through the eyelet of a boot.

Ribbons black as soot, or pink as a pelican’s beak. In my sleep, even,

I bound things up with a flourish, with relish.

My life as a ribbon-maker meant my life was full of gifts.

Still, there was some pain to it. I mentioned the pulling of all my work,

the fraying. I say this not as a complaint, but as a warning.

The ribbon-maker’s calling, though a wonderful art, is a small torment.

I tied my heart to these things, these angel-strings,

these things which are half made to come apart.

Madeleine Fenn

Madeleine (Maddie) Fenn is originally from Tairāwhiti, now living in Ōtepoti and working as a bookseller. She spent a very happy year in 2023 completing an MA in poetry at the IIML.

Poetry Shelf themes: Rain

The day I decide the second Poetry Shelf theme will be rain – and I still have Hone Tuwhare singing his sublime rain poem in my head – there is a sudden deluge of rain slam. Again we lose power out west, and I am sitting in the morning gloom with the slanting storm, musing on how much I love rain poems. Whether it is there in the kinetic water dance on the lawn, in the bulging black clouds in the wintry sky, or a spiral of metaphorical possibilities.

The poems

Rainlight

sun bows

mirrored colours

over

to join beneath us

to hold the water

calm in a bowl

such light

our bread

and honey

Cilla McQueen

from Axis: poems and drawings, Otago University Press, 2001

Hoata: ‘Today’s rain is like television static’

(((((((Medium Energy)))))))

Today’s rain is like television static

so hard to believe that pine trees, swishing

traffic, young harakeke, chirruping

blackbird warnings, are real.

The water tank beyond the macrocarpas

is beautifully round, a rondeau?

While there’s a pile of whenua

dug by the farmer next to it

with a yellow digger

that my boy would love to see

when he’s here next except the digger

has gone for now. The radiata

hold out their hands like candle

holders in the rain——new cones.

Robert Sullivan

from Hopurangi: Songcatcher, Auckland University Press, 2024

Two Waters

All winter the rain blubs on the shoulder of Ihumātao.

The main drag splutters under people’s gumboots.

Children squeal and catch raindrops on their tongues

in the place where the cat got the tongue of their ancestors.

Everything is going on. Laugh and cry and yin and yang,

kapu tī and singing in the white plastic whare.

On the perimeter people hold hands in a tukutuku pattern.

The plans of the developers hologram over the lush grass.

Day and night, police cars cluster like Union Jacks –

red white and blue, and oblique, and birds fly up.

A hīkoi carries the wairua across the grey city.

Auckland Council can take a hike. It’s the wettest winter.

The signatures of the petition sprout from the two waters.

The sky falls into the earth, the earth opens its memory.

Anne Kennedy

from The Sea walks into a Wall, Auckland University Press, 2021

On March 15

A man had taken a knife and sliced straight through the

fabric of the sky.

He made it rain buckets of blood and iron, it clung to the

air like thick glue. Its residue coated every road, pavement

and kōwhai tree in the country. It covered the palms of my

hands and the skin of my teeth and when I walked through

the streets of Newtown it felt like treading through layers

of cement. A stranger had stopped me in the street near

my house, where her face was glowing yellow from the

flickering street lamp above her. She clasped two hands on

my shoulders, with despondency filling the whites of her

eyes and threatening to drown my entire existence. I’m so

sorry, she said, over and over again till the words tripped

and tumbled over each other, bleeding into sentences I

could not dissect.

All I could do was nod and say, Thank you,

because I didn’t want her to take me under.

Khadro Mohamed

from We’re All Made of Lightning, We Are Babies Press Tender Press, 2022

Rainy Country

First on concrete, polka dots appear,

in steady tick-tock to pock dry ground.

Rain begins to throw its weight around:

those tiny splashes that mist the air.

Draw it in pencil, with tentative hand,

squint at its fume, its haze of distance.

Farmers, oilskin clad in drab weather,

are squinting upwards for love or aroha.

The raindrop harbour brings a soakage;

water curves to globes flung along a leaf;

let it weep, blub, gurgle what it believes.

A stone church preens in rain’s light sheen.

From blinked smirr to blind cataract,

never disdain to feel and taste fresh rain’s

nebulous champagne from popped corkage,

as streaks of moisture run and sidle in fine,

crooning triumph from a far corner

of the sky, where they first kept hidden,

among hurl and whirl of low-hung clouds.

On tyre skim, a nimbus shine tells

of roads black as submerged mussel shells.

Park up beneath dripping fern fronds

to watch run-off make tar-seal ponds.

Water slides from slate roof eaves,

backyards brim with sopping fennel,

long grass might be wrung like laundry.

In early hours we hear winter rains

gush through the echo-roar of drains.

Rains sound in chorus, sudden and slow,

or high and faint, or deep and low.

Rains will drench, then are hardly there.

Pristine streams go coursing down

to the cadence chant of drunken rivers,

or else pool and darken in a mountain tarn.

Those afternoons of rain being recollected;

when I’m right as rain, rains make strange;

beyond house windows, their ghosts estrange.

For in the drought we pray for rain, then curse

seven days later when it hasn’t stopped.

David Eggleton

from Respirator: A Laureate Collection 2019 -2022, Otago University Press, 2023

Rain

She’s been lying

on the jetty for weeks,

cheek flat on the wet

wood, mouth an inch

from a fishgut stain,

knife at her elbow.

The rain just keeps

coming down.

She’s as naked

as a shucked scallop,

raw and white

on the splintered planks.

Her breath is as slight

as the sea’s sway.

Up there in the bush

all the trees lean down

and inwards, longing

for the creek,

which longs

for the sea.

And the grey ocean

nuzzles the sand,

its waves as gentle

as tiny licks or kisses,

their small collapse

an everytime surrender.

Don’t touch her.

Let it rain.

Let it rain.

Sarah Broom

from Tigers at Awhitu, Auckland University Press, 2010

Avaiki Rain

as the spring rain

caresses my face

on a distant shore

I find myself longing

for Avaiki

the way

she used to rock

me to sleep

cradle me

in her midnight

embrace

take my muted grief

and grant it the right

to echo

among her slender peaks

in the presence of great chiefs

and fallen warriors

the solace she gave me

when all that was left

was the rain

Leilani Tamu

from The Art of Excavation, Anahera Press, 2014

Blackbird

The rain came in waves all night,

washed leaves from the guttering,

turned trees into disciples of tai chi.

Afterwards, in the swollen darkness

before dawn, before cat stalking

or man and woman rising,

a blackbird sits in a bareness of branches,

like a brushstroke in thin bamboo—

and the man and woman

know nothing of this,

tucked in dreams at the edge of morning.

As the sun pours into the land,

the man rises.

the woman pulls back the curtains

and marvels at the bird,

so still after the storm—

in her beak

the first straw of spring.

Jan Fitzgerald

from A question bigger than a hawk, The Cuba Press, 2022

The poets

Recipient of a Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement, Anne Kennedy is the author of four novels, a novella, anthologised short stories and five collections of poetry. She is the two-time winner of the New Zealand Book Award for Poetry, for her poetry collections Sing-Song and The Darling North. Her latest book, The Sea Walks into the Wall, was shortlisted for the 2022 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Poet, teacher and artist CILLA McQUEEN has published 15 collections, three of which have won the New Zealand Book Award for Poetry. Her most recent work is a poetic memoir, In a Slant Light (Otago UP, 2016). Other titles from OUP are Markings, Axis, Soundings, Fire-penny, The Radio Room and Edwin’s Egg. In 2008 Cilla received an Hon. Litt.D. from the University of Otago, and was the New Zealand National Library Poet Laureate 2009–11. In 2010 she received the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in Poetry. Cilla lives and works in the southern port of Motupohue, Bluff.

David Eggleton lives in Ōtepoti Dunedin and was the Aotearoa New Zealand Poet Laureate between August 2019 and August 2022. Respirator: A Laureate Collection 2019 -2022 was published by Otago University Press in 2023. A limited-edition chapbook of political and satirical poems, entitled Mundungus Samizdat, with drawings by Alan Harold, has been published by Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop for National Poetry Day 2024.

Jan FitzGerald is a full-time artist and poet who lives in Napier. She is the author of four previous poetry collections, the most recent being ‘A question bigger than a hawk’ (The Cuba Press, 2022), and she has been shortlisted twice in the Bridport Prize poetry competition.

Khadro Mohamed is a writer and poet residing on the shores of Te Whanganui-a-Tara. She’s originally from Somalia and has a deep connection with her whakapapa, which is often a huge source of inspiration for her poetry. You can find bits of her writing floating around Newtown in Food Court Books and in online magazines such as: Starling, Salient Magazine, Pantograph Punch, The Spinoff, Poetry Shelf and more. Her debut collection, We’re All Made of Lightning, won the 2023 Jessie Mackay Award for Best First Book of Poetry.

Leilani Tamu is a poet, social commentator, Pacific historian and former New Zealand diplomat.

Robert Sullivan (Ngāpuhi, Kāi Tahu) is the author of nine books of poetry as well as a graphic novel and an award-winning book of Māori legends for children. He co-edited, with Albert Wendt and Reina Whaitiri, the anthologies of Polynesian poetry in English, Whetu Moana (2002) and Mauri Ola (2010), and an anthology of Māori poetry with Reina Whaitiri, Puna Wai Kōrero (2014), all published by Auckland University Press. Among many awards, he received the 2022 Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for a distinguished contribution to New Zealand poetry. He is associate professor of creative writing at Massey University and has taught previously at Manukau Institute of Technology and the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. His most recent collection was Tūnui | Comet (Auckland University Press, 2022).

Sarah Broom (1972 – 2013) was born and educated in New Zealand before moving to the England for post-graduate study at Leeds and Oxford. She lectured at Somerville College before returning home in 2000. She has held a post-doctoral fellowship at Massey (Albany) and lectured in English at Otago University. Broom published her first book of poetry, Tigers at Awhitu, with Auckland University Press in 2010 and is also the author of Contemporary British and Irish Poetry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

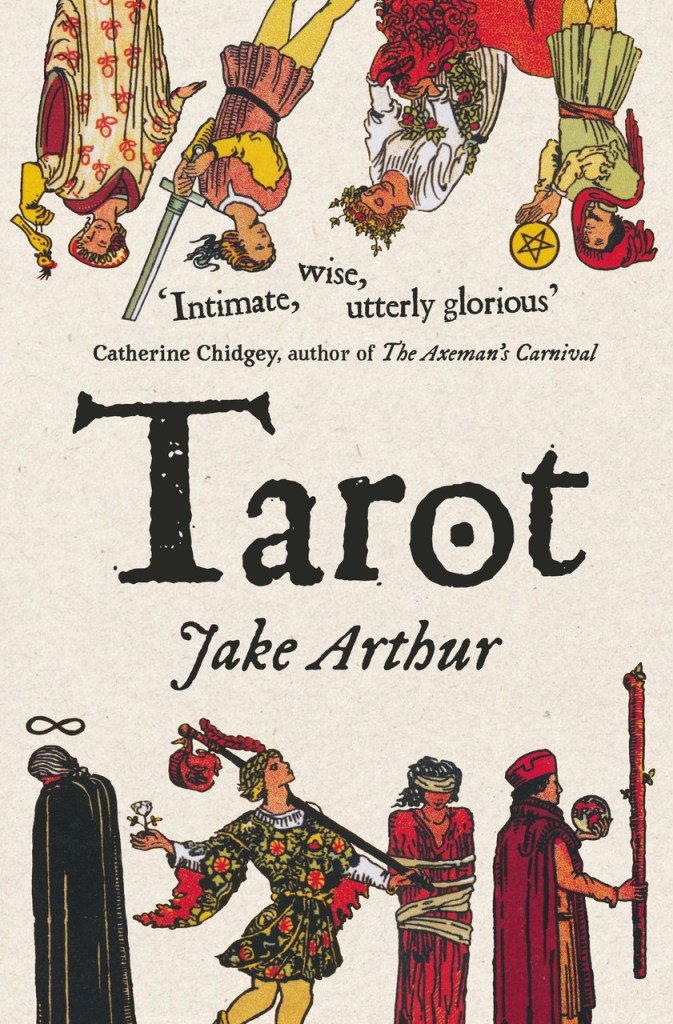

Poetry Shelf review: Tarot by Jake Arthur

Tarot, Jake Arthur, Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2024

You see, it is all a matter of making and unmaking.

To stick, even stasis has to change.

We could go mad in an endless night,

And in an endless day drown

as sure as a wine-dark sea.

from ‘Penelope or Nine of Wands’

After my first reading of Jake Arthur’s new collection, Tarot, I wondered how much poetry joy we can imbibe, for reading these poems felt like I was travelling through a solar system of poetry joy.

Jake uses a deck of tarot cards to build a sequence of characters, loosely drawing upon the depictions of magicians, occultists, lovers, fools, angels in Rider-Waite’s tarot deck from 1909. Pamela Colman Smith’s cover design is based on the deck. We met the Knight of Swords, the Ace of Cups, the Empress, The Hanged Man, and so on. The King of Cups. The Page of Wands. Reading through the deck is a matter of savouring the episodic, the sensual, the treadmill questions, animated scenes.

The characters, usually speaking in the first-person, make interior fears, uncertainties, epiphanies audible. The episodes are grounded in love or daily routine, sex or stasis, movement or self interrogation. Most importantly, I discover a character deck of myriad readings. The initial poem’s tarot reader invites us (‘you’) to read, and from there we move into the heart and trails of reading: tea leaves, the cards, body language, the world, wreckage, melancholy, the divine, mischief, anxiety, daily omens and signs, yourself . . . ourselves, joy. And what I love about this intricate reading experience is how sensual it is, from the haptic to the sighted to olfactory organs, whether whiffs or woofs or brazier embers.

Another joy is Jake’s agile language, the way the stretching, spinning, surprising syntax adds to the carousel of voices. At times, it might be a slippery movement of nouns and verbs, but other times there is an almost archaic glint, the lexicon carrying traces of an elsewhere time or place. Again sustaining and extending character.

His chest is a golden plate

Where she sees herself back in ridges

As though aged by the prospect of him.

from ‘Rest and recreation or The Empress’

Sometimes the sequence has a baroque feel with its drama and heightened movement, or perhaps cubist as the world and the speakers both splinter and cohere, or even impressionist with visible brush strokes and spontaneous vibes. I know zilch about tarot cards but this collection is a reading uplift of signs, signals, sensations. At its core, the universal questions that haunt so many of us. How do we do, how do we go, how do we be, how do we who? Ah, yes, a solar system of poetry joy.

He kept asking:

What do you want to be?

But I wanted to be a who, not a what.

In the future I had different eyes.

I watched my every move.

I stooped to get beers out of the fridge.

I carried suitcases over my head.

from ‘Look up or The Hierophant’

Jake Arthur is the author of A Lack of Good Sons, included in the NZ Listener’s Best Poetry of 2023. His poems have appeared in Best New Zealand Poems, Sport, Mimicry, Turbine, and Sweet Mammalian. He has a PhD in Renaissance literature and translation from Oxford University.

Te Herenga Waka University Press page

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: Ladies’ Litera-Tea 2024

You can purchase tickets and see programme details here

Delighted to see Isla Huia will be appearing – here is my review of her fabulous collection,Talia, and you can also hear her read a couple of poems.

Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku) is a te reo Māori teacher and writer. Her work has been published in journals such as Catalyst, Takahē and Awa Wāhine, and her debut collection of poetry, Talia, was released in May 2023 by Dead Bird Books. She has performed at the national finals of Rising Voices Youth Poetry Slam and the National Poetry Slam, as well as at writers festivals and events throughout Aotearoa. Isla can most often be found writing in Ōtautahi with FIKA Collective, and Ōtautahi Kaituhi Māori.

There are few books I am going to be ordering online! This will be a terrific celebration of books published in Aotearoa.

Poetry Shelf Monday Poem: Indigo by Lou Anabell

‘Indigo’, graphite on paper, 2017

Indigo

for Catherine Salmon

It was dusk when I swam with the dead whale,

but I did not know it was there.

On the shore a group of people began to gather,

I joined them, I saw it – open and rotten.

The flesh hung like icicles,

stalactites tapering from the roof.

Catherine I want to draw it

Three metres; graphite; erasable;

I trace the edges before I begin.

Name it indigo she says, for the colour

of the place we don’t know –

deep in the sea,

deep in the sky.

When my shoulder aches and my palm

is stained silver she says come back

with fresh eyes: which is to walk away

(blind) and come back seeing again.

I never noticed the onset of her dementia,

perhaps it too had a colour.

Lou Annabell

Lou Annabell is a Manawatū born poet based in Te-Tara-O-Te-Ika-a-Maui / The Coromandel Peninsula. In 2023 she completed her MA in Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters.

Poetry Shelf themes: The Moon

When I was an awkward misfit teenager, I discovered Hone Tuwhare in our secondary-school library and his words spun gold and silver and sweet rivers inside me. This is what words can do. How I loved ‘Rain’ and ‘No ordinary sun’. Words have continued to ignite my heart, my senses, the possibilities of the world, transforming pathways to past present future.

Early one morning we were driving to the blood lab, listening to Kamala Harris on the radio, talking to a gathering of people and it it filled me with both joy and hope. The almost-full moon hung in the sky, a bright beauty patch in a sky of pink grey blue, with a collage of clouds, cut-out shapes like a child’s painting. But my eyes kept returning to the moon, musing on the moon, on its enduring magnificence.

When I read a poem and the moon makes an appearance, it’s like a little patch of shine, a beauty prompt, a reading pause of wonder. When I decided to assemble clusters of poems around themes and motifs, especially themes and motifs that have been used for centuries, my first thought was to start with the moon. No matter how many moon poems have been written, whether the moon is the main focus or a sideline glint, it’s appearance can still enhance the reading experience.

So I begin my theme clusters with the moon, and over the coming months will assemble others such as sun, stars, harbour, rain, fancy dress.

The poems

See What a Little Moonlight Can Do to You?

The moon is a gondola.

It has stopped rocking.

Yes. It’s stopped now.

And to this high plateau

its stunning influence

on surge and loll of tides

within us should

somehow not go

unremarked

for want of breath

or oxygen.

And if I

to that magic micro-second

instant

involuntary arms reach out

to touch detain

then surely

it is because you

are so good:

so very good to me.

Hone Tuwhare

from Mihi: Collected Poems, Penguin Books, 1987

VII.

The moon is sometimes just the moon

no one cares about shimmering

no one asked it to glow

did we request this luminosity?

There it is! Just there

still bleached and airborne even

in the cold tick of morning

on my way to teach the poets.

Rose Collins

from ‘Teaching the Poets’, in My Thoughts Are All of Swimming, Sudden Valley Press, 2024

Song with a Chorus

The child stands

in the moonlight on the moon

and bounces slowly.

His mother tucks him in.

The light tickles his chin a little.

Dear one, dear one.

Illness is here with its puzzling song.

It muddles your mind

yet tells the truth. For a while

the doctor remembers his own youth

when he, too, was cute.

My lovely one.

The moon lists to port

then to starboard. It is

somehow charming, the way

a mother weeps.

The tears repeat slowly.

My dear, my sweet.

A tear hits the forehead:

a piece of that great sea

we witness and respect.

A doctor would once have said hectic

but what now to say?

Dear one, my dear.

Meantime the moon is always travelling.

Stones live on its surface.

You throw them and they take an hour to land.

Give me your hand. Hold me.

It goes around the planet.

Oh my dear one.

Bill Manhire

from Victims of Lightning, Te Herenga Waka University Prtess (VUP),

The dark side of the moon

grief is a fist of whirling mussel shells

slicing

scraping

shredding what remains

a white pigeon heard you’d flown the coop

took me gently under his wing

Filemu Filemu Filemu I crooned

offered water

seeds

leftovers

he ate everything except cooked carrots

was a peaceful presence in my dismantled world

one morning Filemu was gone

waning Masina rested instead

on the guano-splattered roof

I ached to patch her incomplete beauty

I am fully present Masina chided. Heal yourself

instead of tinkering with my perfection.

I closed my eyes

saw the dark side of the moon

white feathers falling in the rain

Serie Barford

from Sleeping with Stones, Anahera Press, 2021

Ulysses

-and O yes that night the

moon was like a wet jockstrap

and the poets were all right

after all. He — our hero —

waded into the winedark water

down from the rusty ladder

where orange bloomed on his

palms and — O — he said, like

a man in a newspaper clipping,

mouth like the wide wet clink of

a stray fin — O how heroically

he shivered. No passerbys no nothing,

white endless streams of light on

his fingers turning white with wind.

Endless reams of stars. Sewn brocade.

Everything like everything else except

the crumbling of towers in his brasscoin

face. History involved itself upon him.

He found himself compelled, com-

pelled and con-vinced to stop struggling

against what was always surely coming,

what had slated against his better

judgement, like a shield. And all of Rome

fell in his sandy shoes.

Cadence Chung

How it all began

Such pitiful pleas — her thirsty brats.

Husbandless, she bends her will, grabs

a calabash, heads off through the ngaio trees and mamaku ferns.

Such pitiful pleas — her thirsty brats.

She stumbles. Her curses echo through forest and starlight.

Stuff you, moon,

boil your pea brain with pūhā.

Put your flat head into the cooking pot.

The one time I need you, you hide.

Coward, cheat.

I am the sleeping moon.

An ashen cloud conceals my beams.

I am aroused, enchanted. This is the wife I dream of.

Don’t you know I am no ordinary moon? Did I set the clouds to stall?

There’s no light for Rona.

I slither around her, buffed and highly sexed. She succumbs.

Wrapped in my sensations, my reflected-light limbs — we become lovers.

The story is that she pines for her lost infants. That’s a lie.

We fuse all night long when you are staring up at us. But you can’t see that far.

Just ask her —

Rona, are you happy?

Oh yes, my love

Oh yes

Come lie with me Take off your slippers.

Her brats grow, invent haka.

You know where that got them —

no land, no language.

Free entertainment every rugby match.

Reihana Robinson

from Auē Rona, Steele Roberts, 2012

Moon

Soft. Softer.

I walk across a small carless island when the moon is

at its widest, and once, on a country road, I turn off the

headlights to know the amount of light.

I have also loved the foghorn.

Madeleine Slavick

from Town, The Cuba Press, 2024

The poets

Bill Manhire’s most recent books, all published by Te Herenga Waka University Press / Victoria Press, include Wow (2020), Some Things to Place in a Coffin (2017), Tell Me My Name (with Hannah Griffin and Norman Meehan, 2017) and The Stories of Bill Manhire (2015). He was New Zealand’s inaugural poet laureate, and founded and until recently directed the International Institute of Modern Letters at Victoria University of Wellington. He has edited major anthologies, including, with Marion McLeod, the now classic Some Other Country: New Zealand’s Best Short Stories (1984).

Cadence Chung is a poet, mezzo-soprano, and composer, currently studying at the New Zealand School of Music. Her nationally-bestselling chapbook anomalia was released in April 2022 with Tender Press. She also performs as a classical soloist, presents on RNZ Concert, and co-edits Symposia Magazine, a literary journal for emerging New Zealand writers. In 2023, she was named an Emerging Practioner by the Fund for Acting and Musical Endeavours. She likes to sing Strauss, write art songs, and buy overpriced perfume.

Hone Tuwhare(1922 — 2008) was of Ngāpuhi descent, with connections to Ngāti Korokoro, Ngāti Tautahi, Te Uri-o-Hau, Te Popoto, Ngāti Hine and Ngāti Kurī hapū. He was born in Kaikohe and grew up near Auckland. He was the author of No Ordinary Sun (1964), Come Rain Hail (1970), Sap-wood & Milk (1970), Shape-Shifter (1997), and Piggy-Back Moon (2001), among other books. Hone organized the first Māori Writers and Artists Conference in 1973. He received multiple awards and honours including a Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago, a Montana New Zealand Book Award, was our second Poet Laureate of New Zealand from 1999 to 2001 and received the inaugural Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in 2003. That year, The Arts Foundation named him one of 10 living icons of the New Zealand arts.

Madeleine Slavick writes and photographs. Her books of photography, poetry, and non-fictioninclude Town, My Body My Business – New Zealand sex workers in an era of change (as photographer), Fifty Stories Fifty Images, Something Beautiful Might Happen, My Favourite Thing, delicate access, and Round – Poems and Photographs of Asia. Awards include the RAK Mason Fellowship. Madeleine has initiated and coordinated many community arts programmes – in Hong Kong and Aotearoa New Zealand.

Reihana Robinson (he tamaiti whāngai) is a writer, artist, and environmental activist. Her first poetry collection is part of AUP New Poets 3. Auē Rona (Steele Roberts) and Her Limitless Her (Makāro Press) are her first two poetry collections. She received the inaugural Te Atairangikaahu Poetry Award. She lives some of the year in Montague MA and the rest, near Moehau in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Currently working on two collections of poetry and one novel.

Rose Collins (1977 -2023), born in New Zealand and of Irish descent, was a poet and short fiction writer. She worked as a human rights lawyer before completing the MA in Creative Writing at the IIML in 2010. She won the 2022 John O’Connor Award and the 2020 Micro Madness Competition, and has been shortlisted for the UK Bare Fiction Prize (2016), the Bridport Prize (2020) and the takahē Monica Taylor Poetry Prize (2020). Rose was the 2018 Writer in Residence at Hagley College. She was a some-time litigation lawyer, a beekeeper and a mother of two. She lived in Te Whakaraupō Lyttelton Harbour with her family.

Serie Barford was born in Aotearoa to a German-Samoan mother (Lotofaga) and a Pālagi father. She was the recipient of a 2018 Pasifika Residency at the Michael King Writers’ Centre. Serie performed from her collections at the 2019 Arsenal Book Festival in Kyiv, where the Ukrainian translation of Tapa Talk was launched. In 2021 Serie collaborated with film-maker Anna Marbrook for the ‘Different Out Loud Poetry Project. Her most recent collection, Sleeping With Stones, was shortlisted for the 2022 Ockham NZ Book Awards. In 2022 she collaborated with Dutch artist Dorine Van Meel, whose video and performance piece, ‘Silent Echoes’, was exhibited in various European cities to address colonial practices and climate crisis through poetic contributions.

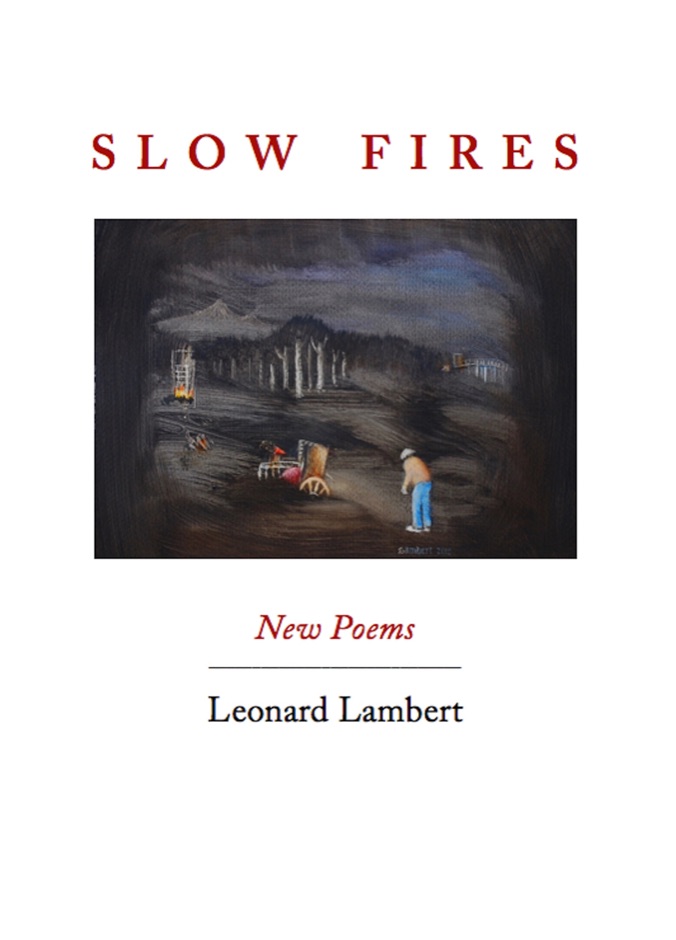

Poetry Shelf review: Slow Fires by Leonard Lambert

Slow Fires, Leonard Lambert, Cold Hub Press, 2024

At the far end of autumn,

the very edge of winter,

the last of the leaves are a-skelter—

a horde of panicky late-goers

some aloft and wind-mad

from ‘Leaving’

Leonard Lambert’s new poetry collection is a beautiful and wry contemplation in late afternoon light, a slow-paced wander through the nooks and niches of old age. The poetry travels through the physical shift in seasons, things that come to the fore and matter, things that slip away and matter so much less. As we move through the poems, wander becomes wonder, and living each day so very precious.

At the core are recurring thoughts and motifs of home, whether fugitive or regained, whether the figure caught by the camera panning finds his way home, or the ghost, or the good luck called to the discharged patient. In ‘Karrinyup Optical Clinic’, Leonard muses on his British parents relocating to New Zealand and Australia, yet never successfully transplant. The poet muse poignantly switches back to himself:

How far-flung & scattered it all now seems,

and you listen for the tribal drum,

the home-song, and wonder if anywhere,

or everywhere, is where you belong.

The title poem, ‘Slow Fires’, resists the magnetism of extremes, ‘Love-Hate, Despair-Delight’, suggesting that in ‘Like & Quite-enjoy’ slow fires are more enduring. And yes, the warm embers are here, in memory retrieval, in the fickle movement of time, in the image of a past self, for example, when the ‘elderly artist returns to his studio after a prolonged post-exhibition break’ in the moving poem, ‘Freeze-frame’:

Old clothes (not so old) are thinner

than I recall, and leather,

so long to last, frays.

Cobwebbed overnight,

I watch this man in his shed

spinning out wonders, and wonder

to myself: was that ever me?

There is a musicality of reflection, the way lightness and seriousness (ah, two extremes with a prismatic bridge between?) overlap. Horizon lines shimmer, haunt and draw closer. Fears and hopes range from intense to faint. This slender chapbook will linger and settle in your inner poetry room long after you put the collection down.

Leonard Lambert (1945) is the author of seven collections of verse spanning almost as many decades. His Selected Poems, Somewhere in August (Steele Roberts) appeared in 2016, and his most recent publication is a chapbook, Winter Waves (Cold Hub Press, 2018). He is a full-time painter who lives in Napier.

Cold Hub page

‘Lost Summer’ on Poetry Shelf

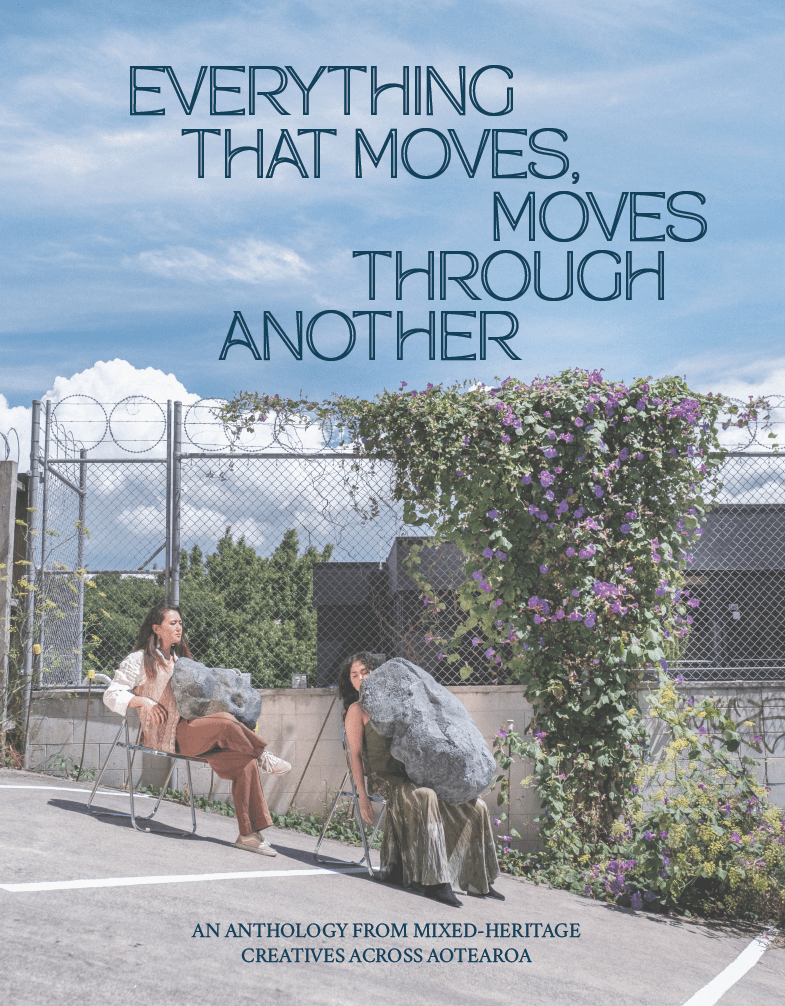

Poetry Shelf review: Everything That Moves Moves Through Another: An anthology of mixed-heritage creatives from across Aotearoa

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another, ed. Jennifer Cheuk 卓嘉敏

5ever Books, 2024

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another is a mixed medium anthology edited by Jennifer Cheuk. The contributors are of mixed heritage and the work includes photography, multi-media art, poetry, prose, essays and comics. The evocative title is taken from Cadence Chung’s poem cycle, ‘Visitations’.

In her introduction, Jennifer talks about her own mixed-heritage experience, the joy of meeting other creatives from mixed-heritage backgrounds, and the resolve to edit an anthology that both celebrates their experiences and highlights corrosive assumptions. Jennifer underlines how important the project is in view of connections and community building. I carried the word ‘connections’ with me as I read, along with the word ‘conversations’. This is an oasis of vital conversation, between the artists and between the works they have produced. It is also a result of community building, as we see in the list of people that supported Jennifer and its arrival in the world.

How timely and important this multimedia multi-heritage conversation is, crossing place and time, autobiography, epiphanies, challenges.

The cover image, ‘Between a Rock and a Hard Place’, is an evocative artwork by Harry Matheson, and like other examples of his work in the anthology, the rock is layered in poignant meaning: I see boulder, weight, screen. I am reminded of poetry collections by mixed-heritage or non-Pākehā poets that reference the plague of questions the writer endures. More than anything, ‘where do you come from?’ and ‘no, but where are you actually from?’, even when the poet is born in Omarama or Ōtautahi or Tāmaki Makaurau.

At times, creating work, whether visual, textual or aural, is a matter of navigating ‘who am I?’, across bumpy terrain, down side alleys and along flight paths, drawing upon precious experience and soaring imagination. It might draw upon what we speak, what we eat, the stories we inherit. These creative works speak to and for and with and of the creators’ mixed heritages.

The opening comic by Kim Anderson shares the experience of growing up Asian Māori by collaging family scenes, graphics, real photographs, self reckonings. Entitled ‘Kim Anderson’s Museum’, it works as a map of the museum and it is so cool, so affirming, it makes me hope every secondary-school library orders a dozen copies of the anthology.

Cadence Chung, a poet whose work I have long admired, has created a sequence of poems, poems that address visitations, from Chinagirl to Scheherazade, Penelope, an unnamed beloved, a dead grandfather. The sequence presents variations on perfection and failure, self doubt and self resolve. The poems stand as vessels to hold close.

Maybe one day the ride home

will not feel like an ending; it will be

another night in the grand progression

of all things. Yes, I cannot paint myself

as beautiful and chinoi, even though

I try. I cannot sleep without trying just

a little, deluded prayer. I cannot even

tell a thousand stories, like the woman

I crave to be. I have not written a thousand

poems. I have only ever written one.

from ‘VISITATION (myself)’

Jefferson Chen’s sequence of photographs entitled ‘blending in standing out’ juxtaposes arresting images (a photograph of a windowed wall, grey, with a mirror image bird and occasional bar codes) alongside text that edges between postcard and poetry. And in the seams of writing and imaging, the plague of corrosive questions throb.

Nkhaya Paulsen-More’s ‘Walking Between two Worlds’ builds a personal lexicon of words that bridge two worlds, South Africa and Aotearoa, a glossary, a guide, links edges harmonies.

Everything That Moves, Moves Through Another is an essential anthology that underlines the strength of conversations that promote connections, diversity, that lay down challenges, that make personal experience count, that encourage us to review who and where and how we are. Today, in this toxic corrosive world, it is so very important. This book is a rich gift indeed.

Jennifer Cheuk, Hong Kong Chinese, Welsh-European is an editor, researcher and curator. She is the founder of Rat World Magazine and is highly involved in the theatre scene as a reviewer and writer. Her interests lie in community arts practices, alternative forms of storytelling, independent publishing and creating more accessible spaces for people to experience the arts.

5ever Books is an underground publishing house based at Rebel Press, Trades Hall in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. They are committed to honouring Te Tiriti O Waitangi in Aotearoa.

AUTHOR AND CONTENTS LIST:

Nina Mingya Powles – a creative response

Kim Anderson — Where r u really from?

Cadence Chung — Visitations

Kàtia Miche – What melts into air?

Damien Levi — Ngā mihi

Jefferson Chen — blending in standing out

Ivy Lyden-Hancy — te manu and the sky waka

Jessica Miku 未久 — What Kind of Miracles

Ruby Rae Lupe Ah-Wai Macomber — My Moana Girls

Ying Yue Pilbrow — Wayward

Emma Ling Sidnam — Sue Me

Jimmy Varga — The Asian

Jill and Lindsey de Roos — What are you?

Daisy Remington — What Makes Up Me

Chye-Ling Huang — Black Tree Bridge

Evelina Lolesi — Self Portrait: Mapping Tidal Whenua

Eamonn Tee — Innsmouth

Emele Ugavule — For Ezra

Harry Matheson — Between A Rock And A Hard Place

kī anthony — Never Quite Home

Maraky Vowells — Created Communicated Connected

Dr Meri Haami and Dr Carole Fernandez —

Kechil-kechil chili padi: Ahakoa he iti, he kaha ngā hirikakā

Nkhaya Paulsen-More — Walking Between Two Worlds

Yani Widjaja — Oey黃 is for Widjaja

Chyna-Lily Tjauw Rawlinson — My Whānau

romesh dissanayake — A Remembered Space

Jake Tabata — STOP FUCKING ASKING ME TO WATCH ANIME WITH YOU

EDITED BY: Jennifer Cheuk 卓嘉敏

PUBLISHED BY: 5ever books (see here)

Check out a terrific review by Hannah Paterson at The Spin Off

Poetry Shelf Monday poem: My Season by Simone Kaho

My Season

A winter walk puts me on a path with peers and their

dogs, kids, or other reasons to be there

I breathe purposefully like a mountain or a train

Last night I dreamt about my love who always a dream, he bought a house at twenty-four and I’m in it again, after a family party, after we’d broken up

his mother is sorting out junk

somebodies’ kids ask if I want to play but I’m already hiding from him

As I leave he turns me by the shoulder, weeping

He is a water balloon and I hold him like a child who won’t throw

He is a red coat and I am his horse charging

My impossibility is as inevitable as spring

My body as helpless as a magnolia tree in bloom

Elegant pink, magenta, and fierce white organs facing the sky

and slowly unpeeling

My fist clenched so tight every cleft and knuckle blushes

The future is in it. My love is in it

I wish to open, for everyone who passes

to open, and shed our isolation

like waxy, lemon-scented petals

like dead skin from angel heels

Simone Kaho

Simone Kaho is a Tōngan / Pākehā writer and multimedia journalist who creates work at the intersection of politics, art, and storytelling. She has a Master’s in Creative Writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters and has published two books of discontinuous narrative poetry, Lucky Punch in 2016, and HEAL! in 2022.