Newborn

His mouth a small red hearth

we huddle around:

forest creatures drawn

to its light and warmth.

When its suck and flicker at the breast stops

we blow cool breath on the soft black coal of his head

to make its wet spark dart again.

A scarlet trapdoor with tiny clapper

that knocks and knocks at our dreams and enters,

his mouth springs open

like the lid of a surprise

to loosen translucent birthday balloons of

Ah, ah.

I, I.

We stand here and watch them rise;

the night crowds at fireworks

make of our own mouths a kind of mirror:

Oh. Oh. You.

Emma Neale

from Spark, Steele Roberts, 2008

Over the coming months, the Monday Poem spot will include poetry that has stuck to me over time, poems that I’ve loved for all kinds of reasons.

I have a poetry room in my house and a poetry room in my head, both excellent places to go travelling. The room in my head stores poems and collections that have stuck with me, whether it is the subject matter, the craft, musicality, an unfolding and enduring sense of awe and wonder. A visiting poet recently admitted (on the radio) they disliked the word ‘inspire’. I dug my heels in, and decided I like a word that evokes an intake of breath, an outtake of creativity. I guess that is what happens when I read poems I love, that delicious intake of breath and that creative trigger. More than anything, heart is always there.

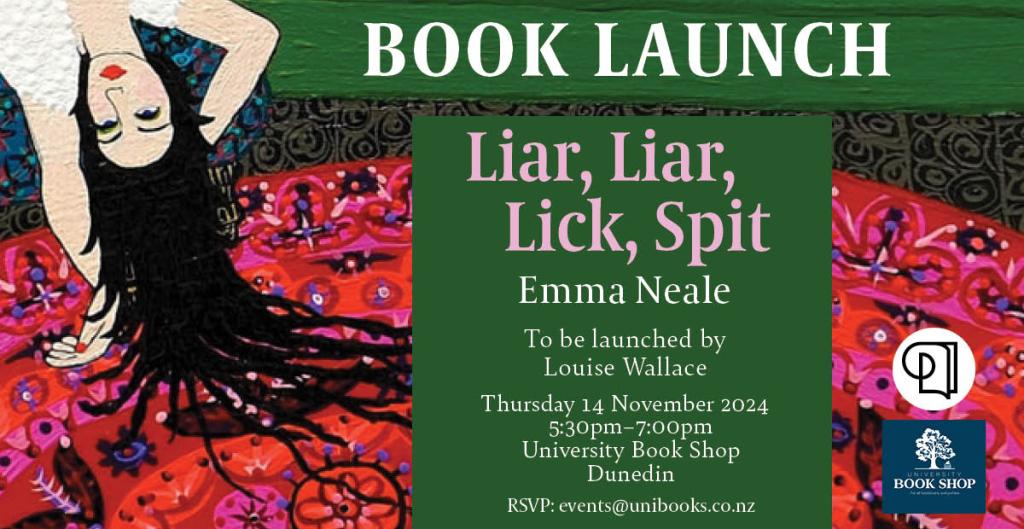

Emma Neale’s poetry collections have struck multiple chords with me – so am delighted her new collection is to be launched on November 14th. A very happy coincidence indeed. So much to admire and celebrate in Emma’s writing. I am drawn into the exquisite craft, poetic rhythms, acute observations, miniature narratives. Her poems are rich in heart, lithe in movement between the domestic and the imagined, the past and the present, personal threads and political challenges. Love is the key.

I picked ‘Newborn’ to go in Dear Heart: 150 New Zealand Love Poems (2012) because the poem catches a maternal moment so perfectly, so surprisingly. The poem exemplifies Emma’s ability to layer a poem like an artichoke, to offer it to the reader to peal back and delight in each petal, and on each reading, take a slightly different route to reach a state of reading wonder. How I love this poem. This heart. Ah.

Emma Neale is the author of six novels, seven collections of poetry, and a collection of short stories. Her sixth novel, Billy Bird (2016) was short-listed for the Acorn Prize at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards and long-listed for the Dublin International Literary Award. Emma has a PhD in English Literature from University College, London and has received numerous literary fellowships, residencies and awards, including the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for a Distinguished Contribution to New Zealand Poetry 2020. Her novel Fosterling (Penguin Random House, 2011) is currently in script development with Sandy Lane Productions, under the title Skin.

Emma’s first collection of short stories, The Pink Jumpsuit (Quentin Wilson Publishing, 2021) was long-listed for the Acorn Prize at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Her short story, ‘Hitch’, was one of the top ten winners in the Fish International Short Story Prize 2023 and her poem ‘A David Austin Rose’ won the Burns Poetry Competition 2023-4. Her flash fiction ‘Drunks’ was shortlisted in the Cambridge Short Story Prize 2024. The mother of two children, Emma lives in Ōtepoti/Dunedin, Aotearoa/New Zealand, where she works as an editor. Her most recent book of poems is Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit (due out from Otago University Press in November 2024).

Launch details