Poetry Shelf Monday poem: Instructions for Performing CPR on Those Already Dead by Molly Laurence

Leave a reply

Instructions for Performing CPR on Those Already Dead

like kissing a dead fish.

purple lips. drop your ego

offer already-breathed

air, scavenged from the shore – coast.

like an [endangered form of] mother – bird;

offer pink mush

of worms pre-chewed.

press it between their stiff lips.

pour yourself uninvited into the smooth

ocean expanse of their chest

agitate it like

molecules gently colliding

and rapidly expanding

to the beat

of pamp – pamp – pamp – pamp

stayin’ alive,

stayin’ alive.

bread dough-pale and bloated

rub rocks and half-arsed arguments

to produce a burnt-hair-static ZAP!

like that scene in the croods

they jolt upright –hair slightly fried– like a resuscitated

seabed mining bill–

good. we’re back in business. now

with the touch of un-/earth upon them–

the fish-eye of tīpuna,

or kaos-or-god still

horizon-wide and unblinking–

ask them the important questions:

at which point in time would you place the divide

between holocene and

anthropocene ?

how would you rate my singularity as an environmental

poet, against all others ?

in which form of future,

or non-life-or-void, do we

consider this an issue

yet ?

Molly Laurence

Molly Laurence is a rangatahi poet from rural Canterbury, studying first year law and sociology at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University. In 2023 she was a National Schools Poetry Award finalist and in 2024 her debut poetry chapbook, Parallel Lines, was released with Ngā Pukapuka Pekapeka Press. She likes nature, advocacy, and funky earrings.

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: (RE) Generation Next – The Poet Laureate Steps Down event

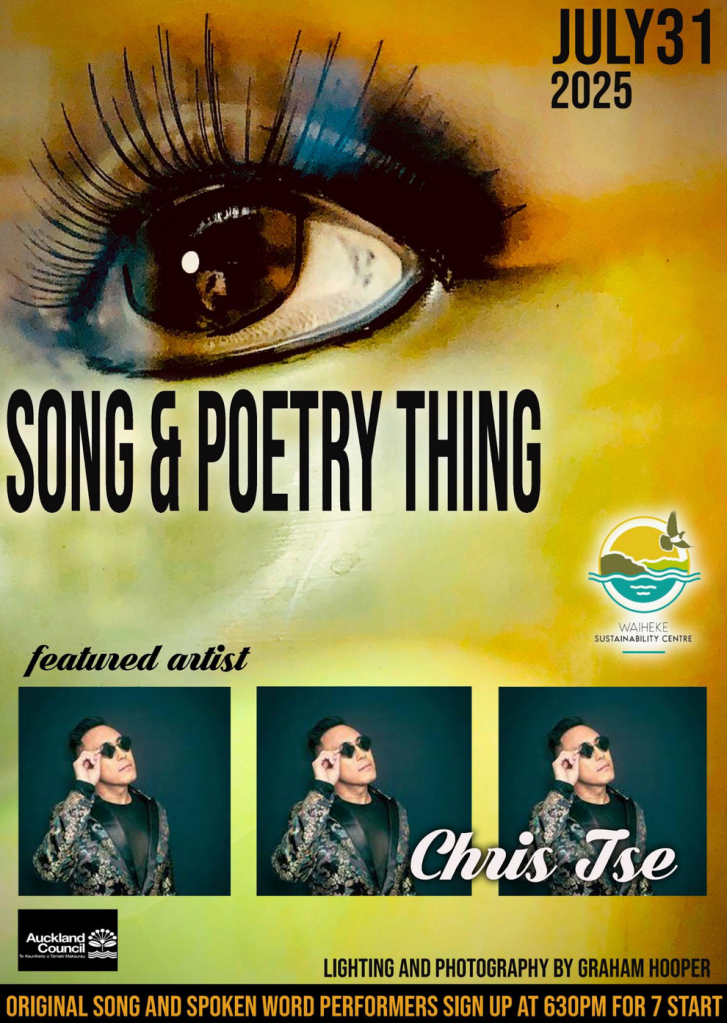

Aotearoa New Zealand Poet Laureate Chris Tse marks the end of his term in this exciting evening with fellow poets Ken Arkind, Cadence Chung, Gregory O’Brien, Chris Price, and Ruby Solly.

Reflections on the future

Join Chris at the National Library to mark the end of his time in the role with his reflections on the future of Aotearoa New Zealand poetry and readings from special guests.

Chris will be joined by poets Ken Arkind, Cadence Chung, Gregory O’Brien, Chris Price, and Ruby Solly.

I left the doors to the past and the future unlocked …

Chris Tse’s three-year term as Aotearoa New Zealand Poet Laureate ends on Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day, when the next Poet Laureate will be announced.

Phantom Billstickers National Poetry Day

About the speakers

Chris Tse (he/him) was born and raised in Lower Hutt, New Zealand. He studied film and English literature at Victoria University of Wellington, where he also completed an MA in Creative Writing at the International Institute of Modern Letters. In 2022, he was named the 13th New Zealand Poet Laureate. His poetry, short fiction, and non-fiction have been recorded for radio and widely published in numerous journals, magazines and anthologies. He has published several collections of poetry and his latest book Super Model Minority (2022) was longlisted for the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2023.

Ken Arkind is an American poet, author, performer, and educator originating from Steamboat Springs in Colorado. He holds the 2006 title of the American National Poetry Slam Champion and the 2010 title of Nuyorican Poets Cafe Grand Slam Champion. Ken now resides in Auckland and is a recent graduate from the Manukau Institute of Technology’s Creative Arts Programme.

Cadence Chung (she/they) is a poet, student, and musician from Wellington, currently studying at the New Zealand School of Music. Her poems started being published in her junior years of high school, and her debut chapbook anomalia was published by We Are Babies Press in April 2022. Her writing takes inspiration from antique stores, Tumblr text posts, and dead poets.

Gregory O’Brien is a poet, painter, author, curator, and editor. His most recent poetry publication is a collection of poems and paintings, House and contents (2022). Other recent publications include a book-length meditation on the Pacific, Always song in the water (2019) and the Ockham award winning book Don Binney: Flight Path (2023).

Chris Price’s poetry collections include Husk (Jessie Mckay Best First Book of Poetry, 2002), The Blind Singer (2009) and Beside Herself (2016). She has also published Brief Lives (2006), an eccentric ‘biographical dictionary’ that samples the lives of both real and fictional characters. Her latest book is The Lobster’s Tale, a lyric essay in conversation with the photographs of Bruce Foster (2021). Chris is a former editor of Landfall, has been a Katherine Mansfield Menton Fellow (2011) and in 2024 held a Bogliasco Fellowship in Italy. She convenes an MA workshop (Poetry and Creative Nonfiction) at the International Institute of Modern Letters.

Ruby Solly (Kāi Tahu, Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe) is a writer, musician, taonga pūoro practitioner, and music therapist living in Pōneke on the old riwai plantation of her Kāti Māmoe ancestors. She has been published in journals such as Landfall, Sport, and Starling, as well as had poetry published in America and Antarctica as well as Aotearoa. Her first book Tōku Pāpā was published by Te Herenga Waka University Press in 2021.

Poetry Shelf conversations: Paula Green and Anna Jackson

In 2022 I had a lifesaving bone marrow transplant and, since then, have been on a long and bumpy recovery road. To celebrate the arrival of my new collection, The Venetian Blind Poems (The Cuba Press) I am creating three features to post on the blog over the coming month, with the help of other fabulous poets. Thank you!

The Venetian Blind Poems, Paula Green, The Cuba Press

Terrier, Worrier, Anna Jackson, Auckland University Press

‘I thought, every body is a memory palace.’

Anna Jackson

‘I will try roaming drifting stalling sailing’

Paula Green

An email conversation: Anna Jackson and Paula Green

Paula: We have known each other for a long time, drawn together by our mutual love of poetry. When my debut collection Cookhouse was published by Auckland University Press in 1997 you slipped a letter in my university pigeonhole inviting me to afternoon tea, and we have been friends ever since. Over the past couple of years, in my isolation period, we’ve had ‘café conversations’ on the phone, filled to the brim with talk of books and writing and poetry. And of course, life. These conversations have been so precious to me.

We both have new poetry books out this year so I thought it would be wonderful to have an unfolding email conversation where we get to talk about reading and writing poetry, and most importantly, our two new books. Like a miniature road trip with no predetermined route or lookout points.

Where to start? For the past few days various ideas fell on the page, but I kept returning to an insistent thought: why poetry matters to me. I guess I have simple answers and complex answers. I have written poems all my life because I love doing it. Writing poetry gives me strength and joy. It feeds my love of music, my intellect, my heart, it offers surprising pathways into the past, the present, into beauty and despair, into humanity. I love how poetry can be so open, so organic.

Why does poetry matter to you?

Anna: I loved your Cookhouse book and I think it is funny how literally I took it – it is full of imaginary afternoon teas with writers, and you were the writer I wanted to have my own afternoon tea with, so I just asked you. I love the way poetry opens up possibilities, on the page and in the world. I thought about answering your question about what poetry means to me in these terms, as an intimate kind of relationship between poet and reader, and as a way of opening up possibilities for actions in the world. But trying to answer completely truthfully about what it is that has kept me reading and writing poetry for more than three decades now, it is really more as a form of art I engage with it, rather than as a form of conversation.

I am endlessly interested in the effects of form, and in how to arrange ideas and imagery in ways that add resonance to meaning, that give rise to a kind of beauty. I would really have liked I think to have been an artist, and to work to create a visual language and visual beauty that would also give rise to thought, but thoughts are my material, words are what I know how to work with, or have practiced working with, and I am no closer to reaching the limits of what I can do with them.

I’m trying to think if this is true of me as a reader of poetry as well as a writer and I think so? I do feel a little in love with poets as a reader, and so I do also think about poetry as a kind of conversation, or as a kind of self-expression – I can fall in love with a voice and want to read anything written by, for instance, Frank O’Hara or Eileen Myles or Amy Marguerite. And I love Raymond Carver’s poetry because I think of him writing it – even though I have never met him (or Frank O’Hara or Eileen Myles). And when I read Cookhouse, I wanted to know you as a friend. So it isn’t just an interest in formal arrangements – and that must be true for me as a writer too. I am not interested in arranging just anything, I am arranging ideas and experiences of my own. But the arrangement matters.

Paula: So much I want to say. I am thinking of poets whose books I have travelled with over decades – Bill Manhire, Bernadette Hall, Dinah Hawken, Elizabeth Smither, Michele Leggott, Anne Kennedy, Robert Sullivan, Selina Tusitala Marsh, Tusiata Avia, Emma Neale, Helen Rickerby – whose work I love so much and with whom I have had uplifting café poetry conversations. I am thinking of the incredible waves of new poets whose work both sustains and amazes me, and I feature this on Poetry Shelf.

I am also thinking of Terrier, Worrier, and how the book’s form, with its loops and patches, its intellectual and emotional rhythms, celebrates, yes celebrates, how poetry can open and re-view worlds, both internal and exterior. So yes, an arrangement that, like a Frances Hodgkin’s still life, offers expansive movement, and out of that movement, an intoxicating interplay of stillness and beauty. And it feels deeply personal. The poetry collections that depend upon, that navigate or have poetic bloodlines in the personal in myriad ways, these are the collections I want to keep reading and re-reading.

Anna: I read The Venetian Blind Poems as your friend, and knowing something about what you had been through, and having had many conversations with you about the politics of the time we are living in, the atrocities we have witnessed, and so of course I didn’t read it just as a formal arrangement of ideas. But I also do love it for its composition, for the way you balance the small, vivid details of a life – the sound of air conditioning, the day-break birds – with the concerns that extend beyond your own experience, your concern for other people, the way your own life is shaped by the news you hear on the radio and read on your phone. And I love, too, the way so much of the imagery is imagined or remembered – you can think of a beach while lying in a hospital bed, you can climb over pain like a mountaineer. Your whole life, in a way, is there in the room with you, even while it is so taken up with the routines of a hospital stay, the comings and goings of nurses, the way symptoms of illness and recovery shape the experience of time. It must have been a challenge arranging all these different things into a collection that moves as beautifully as The Venetian Blinds Poems does. Do you want to talk about this?

Paula: For me it simply comes back to three words: joy, light and love. Writing along with cooking is way of nourishing the joy, light and love that shape each day. And for me, both involve sharing. The Venetian Blind Poems comes out of a tough experience, but perhaps it comes back to beauty. I imagined (and still do) I am climbing a mountain. Yes, it is tough and there are obstacles, but in hospital I would stop on the side of the mountain and pause to look at the beauty view. And still do. My transplant was a gift, and even though I still face daily challenges, each day is a miracle.

I think I should add friendship to my list. I’m sitting here musing on the notion of poetry as friendship. I’m heartened by the acknowledgement pages in poetry books I have read this year, pages that situate the creation of a book within a matrix of friends, along with other writers and their work.

Anna: Oh yes, I like reading the acknowledgement pages too, especially in books by poets who are not part of my own poetry community, when they reveal friendships between different poets I love that I didn’t know were friends. I love to think of them reading each other’s work! Reading poems by friends, or people you want to make friends with, is a brilliant short cut to intimacy, you get to know them not only through the autobiographical details they might draw on, but through the particular way they leap from one idea to the next, the kind of images they think up, what they find beautiful in the world.

Returning to the question of the relation between poetry and beauty, there is so much beauty in The Venetian Blind Poems, in images like the moon shining through the blinds in the hospital, or the sweet-talking light that the hens respond to when you are back home in Bethells, looking out at a view you say you could make sugar from! And there is a beauty too in the arrangement of ideas and metaphor and in the movement through time that the collection gives us. I know you were an artist yourself before you were a poet, and your partner is an artist, so I’d be interested in what you have to say about the relationship between poetry and visual art, and the importance of beauty to you as a poet.

Paula: I love your drawings. I have one on the wall above my desk. You should do more! There is a long line of artists in my family. Colin McCahon once lived in a shed at the bottom of my mother’s garden. Toss Wollaston is in my family tree. I would stay with my artist uncle in Mapua, he would get out his paints for me, and I fell in love with painting. When Michael and I met in London we knew we wanted to be together, and that we wanted to write and paint no matter how poor we were, and we have done that. I get to walk up the hill to his studio and get an incredible uplift from his work. And I can go to exhibitions now.

When I initially view an exhibition or read a sublime poetry book, I move beyond words, into a state of intellectual and emotional uplift. A state that may move into narrative or ideas or memory or feeling. I felt that after reading Terrier, Worrier, it took me ages to find a way to review it, to find a form and an arrangement that opened the book for the reader.

There were so many lines I wanted to quote from your book in my review – ideas that would expand as I moved through the day. For example:

I felt as if my own life were like that dream in which you climb some stairs in your house and discover a whole additional room, or a whole

series of rooms, you didn’t know was there.

I love this idea. I definitely have rooms in my head! It got me musing on connections between writing and space and discovery. Is this key for you too?

Anna: I think that’s a common dream, finding you have more rooms in a house than you knew you had? And I think it does represent an opening up of the self. I think I even read that in a dream dictionary! And I think poetry does build rooms that expand the sense of self and gives you more room in the world. I think art does too. I draw all the time, actually, or often, anyway, but I don’t usually keep my drawings and I wouldn’t want to exhibit them, they are just for me, something I like doing. To be an artist I think is more than drawing, or painting, or it would have to be for me to think of exhibiting – it would be more of a conversation with the world, perhaps, than my drawings are, I would have to think in terms of audience, and in relation to other art.

I am secretive about playing the piano too, and singing – I have no interest in performing. But I don’t know if I would write poetry if I didn’t think I would publish it, or if I did, it would be a different kind of activity. How strange. What is the relation for you between writing and publishing? Does it change the nature of the work, do you think?

Paula: Interesting question. I have so many secret manuscripts I have written over the past couple of years and every single one I wrote out of a love of writing. Some I might like to see in book form, some I might not, but I would never sacrifice my voice or vision in order to be published. Working with Harriet Allen on 99 Ways into NZ Poetry, and with Nicola Legat on Wild Honey: Reading NZ Women’s Poetry were special experiences. Working with Helen Rickerby for many years on poetry collections was equally special. The past three years I have experienced multiple forms of isolation, but my secret writings and my public blogs have been vital engagements with the world. They both matter to me far more than being published. I love talking about poetry books by other people, but talking about my new book takes me back to such an extraordinary time, both on the ward and on my recovery road, I am cautious. Illness is a tricky thing. How do we talk about it? How do we care about it? How do we listen?

I was thinking about secret writing, and how poetry collections, especially sequences such as Terrier, Worrier, both mind and heart fluent, come into being. Did its arrival surprise you? Like opening different doors and windows onto the world and self? Like discovering different poetry trails?

Anna: My secret writing is mostly just stories in my head. I’ve been interested lately in books that include day-dreaming as part of the narrative – Rosalind Brown’s Practice, about a student who is trying to write an essay on Shakespeare’s sonnets, opens out into the most extraordinary day-dreaming sequence, so true to the experience of inhabiting an imaginary self, allowing a story world to come into a kind of reality overlaying the actual reality. And Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19 also has a story of a story inside it, a kind of written day-dream. Both of these narratives of day-dreaming feel astonishingly transgressive to me – so revealing of an interior self! Which is odd because what else is poetry?

Terrier, Worrier was a surprise to me, yes! I wasn’t planning on writing it. But I had recorded some thoughts, over about 3 or 4 years, including the lockdown years, as a blog on my website, that was semi-public – I had a link to the blog on the website but not many people ever read it. So it didn’t feel published, exactly, but not quite secret either. I considered going through the blog posts and turning them into sonnets, or giving them a rhyme scheme, and I also considered expanding the ideas and developing the logic of each thought, and perhaps developing a logic connecting them to each other. Instead, I took out an image, or a fragment of thought, or a few connected points, from each of them (or, not all of them – maybe about half of them), and pieced these extracts together in the fragmentary way the book works now, letting the connections between different ideas resonate in a more open way, and adding in additional thoughts, observations and reading notes, thinking more about the rhythm of the text than the content. I liked the thoughts much more when they were cut short and had some space around them.

Tell me about the process of writing The Venetian Blind Poems – they are set in the time of your hospital stay but were written later. Did you draw on written notes or just on memory? Were you writing poetry in hospital, in your head or on the page, or just thinking poetry, or did the poetry come later?

Paula: I love how fragmentation, space, openness and openings work together in Terrier, Worrier, so it is fascinating to hear their role in the process of writing it. I was ‘writing’ in my mind on the ward – in one of those secret head rooms – but I was on morphine for pain and every now and then things would spill out. I would create line fragments, reciting them like beauty echoes in my mind, especially when things were tough, to help me step outside physical challenges. I think I was assembling drifts of poetry in my head. Sometimes I jotted poetry drifts in my notebook along with blood results and the water sipped.

Back home, I wrote it in a big beautiful notebook. The first section, ‘The Venetian Blinds’, was a mix of memory fragments and notebook drifts. It’s why there’s a strange rhythm sometimes, with miniature snags, jarrings and arrivals, along with sweet currents. The second section, ‘Through the open window’, is one-hundred percent back home where the miracle world is an incredible mix of wonder and fragility. It felt like I was writing poetry with a miracle pen, in a world that filled me with despair as much as it filled me with wonder.

Somehow through this, I’ve also been reading and reviewing books for Poetry Shelf. Taking time to read and write slowly. To open the possibilities for poetry book reviews wider. My slow pace and personal approach means I don’t complete as many reviews as I would like. But I love doing it so much.

I have been thinking about how writing is both words and beyond words. When I write a poem, I’m taken beyond words to a state akin to listening to music or watching pīwakawaka dance beside the kitchen window. And it’s exactly the same when I read poetry collections that carry me beyond words before returning me to the exhilarating moment of writing a review. These are the books that stick to me regardless of form or style, voice or subject matter. I often wonder how I’ll ever manage to review such books without shutting them down for potential readers, without placing limits on the possibilities of reading. I am currently reading Josiah Morgan’s breathtaking collection, i’m still growing and I’m at the point of being beyond words I love the poetry so much. I felt this with Terrier, Worrier and ended up writing a review loop in nine parts.

Do you find writing is both words and beyond words? Every book I review – I am stalling on the word review here and might write a piece on it for the blog – I discover something different about poetry writing as a process. Any thoughts on this?

Anna: I love the idea of poetry drifts, and the idea of creating beauty echoes in the mind, and I love your account of how the book was assembled out of notes and memories, out of poetry drifts and notebook accidents, and completed in that time of miracle and fragility. I know what you mean about the beyond-words aspect of poetry – but I don’t know if I can find the words to talk about it! Maggie Nelson writes in The Argonauts about Wittgenstein’s idea that “the inexpressible is contained – inexpressibly! – in the expressed,” and I find myself talking to poetry students about how a poem can “mean more than it means” – stopping by some woods on a snowy evening becomes about more than stopping by some woods on a snowy evening, without ever being precisely about anything else. In my poetry class I call this “resonance” – the way a poem kind of thrums with meaning, through the ways different ideas, or images, or events, or objects are placed together in the same textual space. But you have to use words to make the words mean more than the words do!

In your work, you often use abstract words in a way that seems very concrete, while filling the poems, too, with material objects that seem to shimmer with meaning. This is something I’ve always loved about your writing. In Cookhouse, for instance, several of the poems have an item of food as the title, then a more abstract phrase or couplet to follow:

iced water

the perpetual sense of the little piece

Relishing stroke upon stroke

gelato

habits harbouring no conclusions

in my moment of heat

I found these poems mysterious and compelling, I loved the way the iced water or gelato anchored the lines that followed into something I could picture, but I also loved thinking of the habits that harbour no conclusions, the perpetual sense of the little piece, and how these ideas might both attach to the objects that gave rise to them but also how they might float free from them, and I found that after reading Cookhouse all the objects around me became magnetised with the potential to attach meaning.

The Venetian Blinds poems work a little differently but the effect is still to layer meaning on meaning. There is a lot of figurative imagery, which in itself seems to me to lean towards abstraction, in the sense that as soon as you compare one thing to another it becomes at once both things and neither thing. But you are more often bringing different concrete, material things into relation with each other rather than relating an abstraction to something concrete. So, you write for instance:

At dawn the air conditioning

is the sound of rain on a tin roof

and then water dripping in distant bush

Or, writing about the hospital food (I found this very funny):

It’s a solid square of inedible fish pie

slathered in Thai coconut sauce that reminds

me of cotton wool and saltless sea foam

And along with the details of hospital foods, nurses coming and going, the view from the window, changing light, changing sounds, there are memories of other views and objects and occasions, and daydreams of other places, thoughts of what is going on elsewhere, so everything is at once concrete and material but also often belonging to dream or memory or imagination. And then you are also concerned with writing about pain, illness and fear in concrete terms, imagining pain as a box, or recovery as a mountain. And poetry itself you think of in visual terms, you talk about driving a poem at low speed so you can enjoy the view through the window, and you even have an image for the relation between the expressed and the inexpressible:

Whenever I open a poem

there’s a curious river

between what I write

and what I don’t write

Paula: Driving a poem – whether as reader or writer! Writing and reading is a crucial form of travel for me. The word that comes to mind as I reread your book again, is movement, that sweet satisfying sensation I accrue as both reader and writer. I am thinking intellectual, emotional, mnemonic, self-nourishment, musical. When I reviewed your book, I created a loop review in nine parts, and movement was a vital ingredient in each section. That and thought.

I enter your poems and I am re-viewing thought, moving across a bridge between one idea and another, along currents of thinking that expand and condense. I read: ‘every body is an emergency room’ and then ‘every body is a memory palace’. I am crossing a bridge into self and then into poetry. Could I carry the emergency room and the memory palace over to the poem? Think of the poem as emergency room? As memory palace? I love this. It resonates so acutely with The Venetian Blind Poems.

Your title, Terrier, Worrier, with its foraging dog image and fretful thinker, offers multiple gateways into movement. You write:

I thought, a terrier is a good symbol for the work of digging up

something underground but still alive.

Again I lead an idea over a bridge to self and then to poetry. To the making and the reading of a poem. And as you indicate with my collection, there are the vital anchors in a physical world. Your thinking, for example, finds roots or starting points in your hens, the birds you observe, the floor tiles, the concrete slabs you photograph, as much what you read, experience, remember.

Thinking, I am surmising, is a relative of wonder, with its attraction to both questions and awe. On each occasion I read Terrier, Worrier, I am wondering. It’s like you are opening both the emergency room and the memory place for us as readers, to let us feel and think the looping ideas, the attachment to beauty and art, to empty space and infinity possibilities.

In this piece, for example, I grasp the need for similes as much intentions or plans, especially how the similes you include add taste and texture to your curling thoughts, as though you are sprinkling grated ginger or finely chopped curly parsley over the writing, the thinking:

I thought, I feel like we ought to acknowledge our feelings,

but I also feel like we ought to then present thoughts, and

claims, that can be challenged and which could be backed

up with evidence, and we ought to act on our claims and the

implications of them. And, I thought, I feel like the phrase

‘I feel like’ ought to introduce a simile at least as often as a

thought or an opinion or a plan. I wanted to feel like a leaf

but I felt like a sink of dirty dishes.

I am about to begin a sentence with ‘More than anything …’, but what follows keeps changing, because Terrier Worrier, offers so many rewards. But I think the word I return to is nourishment. More than anything, the collection nourishes me. The idea that thought, feelings and dreaming, along with poetic devices, form and tempo, are sustenance. Poetry is nourishment, and in this uncertain world, that matters. To that I am adding preparing meals, baking bread, keeping my two poetry blogs active, connecting and engaging with family, friends and other writers.

What matters in our days? What matters in these catastrophic times is how we nourish ourselves, each other, our planet. And writing and reading poetry is one small but vital form of doing this.

Watch Anna Jackson in conversation with Amy Marguerite and John Geraets

Auckland University Press page

The Cuba Press

Poetry Shelf Monday Poem: Crete: A family villanelle by Harry Ricketts

Crete: A family villanelle

The sun flashes pocket mirrors off the sea;

sweet, gritty coffee; cicadas; heat;

old stones; lost gods; ghosts and griefs.

The water smooth as liquid silk.

Jamie strikes out for the horizon.

The sun flashes pocket mirrors off the sea.

Icarus still hang-glides in the empyrean;

Theseus and Ariadne hurry down to the ships.

Old stones; lost gods; ghosts and griefs.

‘So,’ says Jessie, ‘what are the plans for the day?’

Scruff miaows; Scrap sidles; cats everywhere.

The sun flashes pocket mirrors off the sea.

Down here, the remains of a German plane;

up there, partisans and Kiwis hid out in the hills.

Old stones; lost gods; ghosts and griefs.

Bene wins every hand at O Hell.

Francis and Arya like the jet skiing best.

The sun flashes pocket mirrors off the sea.

Old stones; lost gods; ghosts and griefs.

Harry Ricketts

Harry Ricketts is a poet and literary scholar and has published around 30 books. He has lived in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, since 1981. Until his retirement in 2022, he was a professor in the English Programme at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington. His books include the internationally acclaimed The Unforgiving Minute: A Life of Rudyard Kipling (1999) and Strange Meetings: The Lives of the Poets of the Great War (2010). Recent poetry collections include Winter Eyes (2018) and Selected Poems (2021). With historian David Kynaston, he is the co-author of Richie Benaud’s Blue Suede Shoes: The Story of an Ashes Classic (Bloomsbury, 2024). His two most recent books with Te Herenga Waka University Press are the memoir First Things (2024) and the poetry collection Bonfires on the Ice (2025).

Poetry Shelf noticeboard: Poet Laureate Chris Tse – two Auckland events

Chris Tse is thrilled to be performing as guest poet at two long-running poetry events in Tāmaki Makaurau at the end of July. These will be some of his last events during his term as Poet Laureate. Looking forward to hearing from local poets at the open mic section of both events!

Tuesday 29 July, 7.30pm

Poetry Live!

Cafe 39, 39 Ponsonby Road

Thursday 31 July, 7.00pm

The Song & Poetry Thing

Waiheke Sustainability Centre, Mako Street, Waiheke

Poetry Shelf Monday Poem: Space Travel by Dominic Hoey

Space Travel

there’s no gravity around u

I am loose threads and concern

floating in your wake

everything weightless when u speak

a song

echoing deserted corridors

something’s wrong

can taste it in the air

yet nothing phases u

like you’ve read the last page of our lives already

the stars watch

as everything breaks apart

money and promise reborn as wreckage

but I been filling them long nights

with thoughts

like maybe this is a heaven

knowing your fate so certain

and to be adored

even for a breath

as close to god

as any sane person gets

sharing the last of our oxygen

we drift out together

beyond the imaginations and dreams

of everyone we ever loved

Dominic Hoey

Dominic Hoey is a poet and novelist trying to write love poems in late stage capitalism.

Poetry Shelf poems: Peace by Paula Green

Peace

20 May

What if I made up a poem about a house

on a hill with views of the sea and passionfruit

vines laden, and a woman knitting stories

of family connections and sublime epiphanies

into socks and scarves and comfort blankets

with an abundance of vegetables in garden plots

and fruit on the trees and soup simmering

whatever the season and how she is always content

in her own company but one day she opens

a newspaper and it is full of war and plague

and bullies and hunger and racism and side-lined

histories and abusive relationships, underfunded

hospitals and underfunded schools, and she

looks at the olive-green sea and she smells

the tomato soup simmering the fresh basil aromatic

in the air and she turns on her radio and hears

the voice of a young Palestinian student

begging the world to listen, begging for freedom

for her people and how the relentless bombs

trap everyone in houses and how aid can’t get

through and how nowhere is safe and how

everywhere is under attack, and the woman

on the hill tries to imagine the terrified children,

the lack of news and power and water, and how

the catastrophe goes deep into roots and land and home,

and how they cannot pray safely in mosques, and how when

Palestinians resist they are terrorists and their resistance

is deemed invalid, and the woman on the hill looks

at the patch of blue sky and the free-floating clouds

and puts down her knitting with its happy stitching

its loving connections and storytelling skeins

and tells the olive-green sea that we are all

human, and we all need to eat and feel safe,

to stand on soil we call home, to speak our mother

tongues, tell our grandparent stories,

and to feel the depth and caress of peace

Paula Green

20 May 2021

Every Thursday in 2021 I wrote a poem, and now have a manuscript sitting in my drawer called ‘Thursday Poems’. I was flicking back to see what I had written in July but stalled on this one. It felt like I could have written it today. What has changed globally or locally? How have things improved in Aotearoa as the gap between the rich and the poor widens? Our environmental aims deteriorate? As the situation in Gaza is even worse? As peace in the Ukraine is elusive? I recently signed an open letter, along with other writers and publishers, calling for an immediate ceasefire that Mandy Hager organised. I would like to see an open letter addressed to our Coalition Government demanding to see how they will repair our country rather than damage it so cruelly. Nest year we will be voting.

Poetry Shelf review, reading and interview: The Anatomy of Sand by Mikaela Nyman

The Anatomy of Sand, Mikaela Nyman

Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2025

I often ask poets how what is going on in the world affects their writing, if not their ability to write. Their answers occupy myriad points on a spectrum, from writing as solace to writing as protest. Mikaela Nyman’s new collection, The Anatomy of Sand, draws our environmental relationships into view. It’s a version of holding up protest placards (and we are doing much of this on the streets) by using poetic forms to revisit human impacts upon nature, both good and bad. Mikaela draws upon many sources to furnish and advance her poetic spotlight: scientific research, Finnish myths, the work of other poets, artists, inventors, engineers.

The cover image is as haunting as the collection’s title. The enigmatic glass sculpture by Ellie Field, photographed on a beach setting, is open to multiple readings. I jot down words: fragility, sur-real, melancholy, intense mind and heart concentration. The image sets the title vibrating as the word and idea of “sand” explodes in multiple directions. Hmm. I am standing barefoot on the beauty of beach sand. I’m holding a sand timer wondering if time is running out, recalling the way sand slips through fingers, is dredged and transported elsewhere, is conserved by locals as a vital home for native birds under threat.

I read the first poem, ‘Lonely sailors’, and am again caught in a matrix of melancholy, enigma, physical and historical debris on a fragile shoreline. The final line sticks to me as I read the whole collection: ‘knowing // that we’re sailing too close / to the wind’. We are simply sailing too close to the wind and it hurts.

I shuffle back to the preface quotation by Rachel Carson from Silent Spring and it feels like a lifeline for us all: ‘In nature, nothing exists alone.’ And herein lies a reason to keep writing, to keep connecting, whether for solace or protest and everything in between. I add to that Margaret Mead’s declaration: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed it is the only thing that ever has.” And I want to say, clearly and insistently, Mikaela’s precious book promotes the idea that poetry does not exist alone.

Poetry has the ability to be the glass sculpture on the beach, a prismatic form that might be personal, political, philosophical, elliptic, searching, intertextual, rich in narrative, surreal. Pick up the book. Move from the seed collectors to the tree planters, from the separation of metals to the disposal of milk on the land, from the ownership of sand to feeding on Hope Cafe’s sandwiches and leeching on hope. Circle around notions of balance, the sight of shoreline debris, prophesies in a gallery soundscape. Flick back to ‘Cilia’, and revisit the weight of the world, not just today, but across generations (Mormor means ‘mother’s mother’ in Swedish). How this glorious poem catches me:

Unable to heed the warning I carry the world’s worries

on my hips. Too late

to tell Mormor I now understand

what she was on about, why her hips

were so wide you could spread

one of her fine embroidered tablecloths

over them and invite the whole neighbourhood

for a feast.

Mikaela writes with a multi-toned pen, her lines delivering technical information alongside moments of awe, wonder, contemplation. Listen to her read below, listening to the shifting tones of ache and gentleness, jagged edge and lilt, the sonic flurry dancing in the ear, urgently. Oh so urgently. Perhaps we are all standing on the shoreline as we read, as we reconsider our actions and choices, yes absorbing beauty and life, but re-examining how to heal rather than damage the environment. Our environment. In reading this collection, we inhabit the poem, and then, with Mikaela’s visible signposts, we move beyond the poem, mindful of past present future, to the collective power to do and to hope. Thank you.

a reading

‘pear lizard plumage’

‘Mudlarking’

‘Of orfes and alder’

an interview

Were there any highlights, epiphanies, discoveries, challenges as you wrote this collection? This is your first book written in English – how was that?

Someone wise said “every poem is in search of a collection,” which may or may not be true. What is true, is that every poem that elicits a response from someone along the way gives me a boost and strengthens my resolve to stick with the more expansive project. I do become obsessed with certain issues, themes and observations, and tend to follow that enquiry to the end. Sometimes there’s a happy ending. At other times there is no end in sight, so I have to draw a line and say enough. What this means, is that some poems end up being closely linked – in theme, tone, place, imagery, format – as they emerged around the same time. Over time, however, when the focus shifts to new territory, older poems may feel obsolete, or they don’t quite fit in. Just because poems have been individually published or placed in competitions doesn’t mean they should automatically be included in a collection.

And then we have the whole problem of translation. Since I write in both English and Swedish, I play around with words a lot. I don’t always know if a poem sparked to life in English or Swedish. I waste a lot of time translating myself into the other language and back again, continuously polishing it. In the process something alters, it becomes a different beast. With The Anatomy of Sand, I was never sure how much of my own Nordic ancestry, history and mythology to include. Would it even be remotely interesting to anyone else? At one point, all the Nordic elements were taken out. Self-doubt is a constant companion.

I find moving between other languages can create such different music! Along with everything else. What matters when you are writing a poem? Or to rephrase, what do you want your poetry to do?

Each poem is its own contained world, it has to carry its own emotional truth. The aural quality of hearing a poem read out aloud, how the words roll off the tongue, the rhythm and sounds, and how it impacts the listener matter to me.

Are there particular poets that have sustained you, as you navigate poetry as both reader and writer?

I read widely, in several languages. Some of the poets that have sustained me over the past few years include Tua Forsström, Finland’s most celebrated contemporary poet. Like me, she also belongs to the linguistic Swedish minority. Her poetry can be dream-like and moody. Reading her makes me want to row out on a lake at night, light candles in the snow, and watch Andrei Tarkovsky films.

Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer’s poems tracks the changes of seasons, using surprising word choices and imagery. His poems ooze with nature’s atmospheric beauty and a sense of mystery that fills me with wonder and awe when I read him.

Padraig O’Tuama’s podcast ‘Poetry Unbound’ has steadied my ship and kept me company when I wake up at dawn and wonder if the world is still intact. I’m grateful to Hinemoana Baker for putting me onto Padraig. Hinemoana’s Funkhaus is one of my favourite New Zealand poetry collections.

Ada Limón was the first Latina to be named Poet Laureate of the United States. I wonder how she is faring now… I love how she can pick up some mundane detail and turn it into something astonishing. The way she depicts human relationships with nature evokes an Oliverian sense of gratitude for being alive. I think we need that, more than ever.

We are living in hazardous and ruinous times. Can you name three things that give you joy and hope?

My family, nature, collaboration with generous creative human beings across all art disciplines.

And for me your book! And picking up on poets and filmmakers to return to (Tarkovsky and Limón) in interviews and the poetry books I am reading.

Mikaela Nyman is from the autonomous, demilitarised Åland Islands in Finland and lives in Taranaki. Her climate fiction novel SADO was published by Te Herenga Waka University Press in 2020. Her two poetry collections in Swedish were nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize in 2020 and 2024 respectively. Her second poetry collection, To get out of a riptide you must move sideways (Ellips), connects Taranaki and Finland and was awarded a literary prize in 2024 by the Swedish Literary Society (SLS) in Finland. In 2024, she was the Robert Burns Fellow.

Te Herenga Waka University Press page