Poetry. Dear old poetry. Your rusty relics groan on forgotten shelves of secondhand bookshops – Wordsworth and Shelley bearded with cobwebs,

Spenser dispensed with, the pages of both Brownings gone brown. Look,

there’s an abridged Longfellow leaning for support against a broken-backed

Bracken. But no, it’s not over. It’s never the end. Poetry lives on. Its voice

is stuttering within us all. A waitress smears mist from a restaurant window and seizes the day in a heartbreaking haiku.

Poetry. Yup, poetry. Musical emotion. Seraphic utterance. Precise notation

of our hearts’ desires. The phantom Muse floats high above city chimneys.

Anguished zealots spy her, exclaim, leap madly at her ankles. A few even

succeed and are borne briefly aloft, clinging to the Muse’s toes and warts

and corns, singing loudly down to the rooftops that our lives are noble and

signify.

Poetry. Sweet poetry. It’s a contagion, let me warn you, an epidemic. The

whole city’s at it. There are sonneteering plumbers out there, lyrical clerks

and romantic drain diggers. Classicist butchers are chopping up trochees

and iambs with their tripe and lamb. Wharfies wail oceanic epics. Sad-eyed

masseuses devise Buddhist mantras in Thai. The Nuns jabber limericks. An

elegiac taxi driver honks past with a carload of rowdy symbolists.

Poetry. Wow, poetry. What a comfort, what a blessing, what a boon, for

those of us who can’t jog, juggle, sew, whistle, turn cartwheels or make

money, who topple from tightropes and sing like cats caught in a

dishmaster, whose thuggee fingers maim any instrument they touch. Words

– words are all we have. And they escape our needy grasp like startled eels.

Iain Sharp

from ‘The Poets’, in The Singing Harp, Earl of Seacliffe Art Workshop, 2004

Iain Sharp (1953- 2026), librarian, writer, poet, performer, reviewer, lover of books, was born in Glasgow, and arrived in New Zealand in 1961. He ended up settling in Nelson with his beloved wife, Joy. He studied English at the University of Auckland, before enrolling at library school at Victoria University Wellington. He worked at the Sylvia Ashton-Warner Library at the Auckland College of Education and as a rare books assistant at the Grey Collection, Auckland Public Library. In 1982, he completed a PhD at Auckland University (Wit at several weapons: a critical edition, 1982), that considered the 17th century comedy by the Jacobean playwright and poet Thomas Middleton and William Rowley.

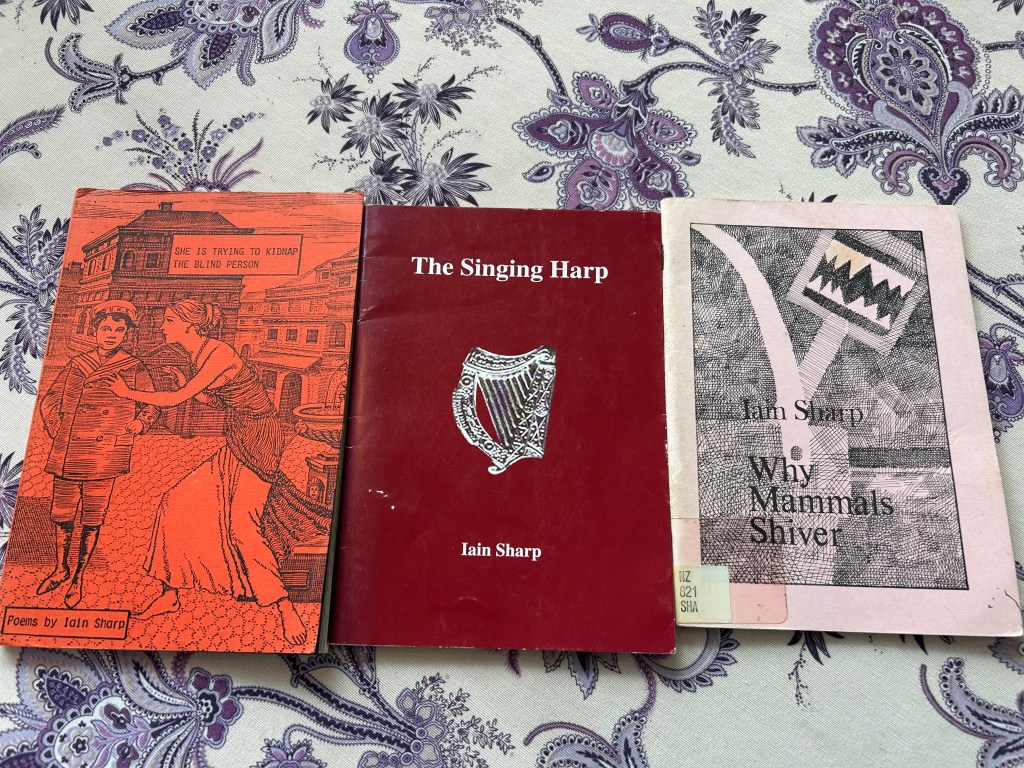

As a nonfiction author, he wrote Sail the Spirit (Reed 1994), a book on Auckland City Libraries treasures: Real Gold (2007) and a book entitled Heaphy (AUP, 2008). His poetry collections include Why Mammals Shiver (1981), She Is Trying to Kidnap the Blind Person (1985), The Pierrot Variations (1985) and The Singing Harp (2004). Along with poets such as Dave Mitchell, Michael O’Leary and David Eggleton, he performed his poetry at the Globe Tavern in the late 70s and early 80s, and the Shakespeare Tavern in the 1990s.

Reading Iain’s poetry again, is to get his incredible wit singing in my ear, to savour the intoxicating amalgam of music, surprise, love, living and reflecting in the moment, writing and performing in the arc and loops and riffs of what poetry and life can do. I am moved and I am inspired. Utterly. I so loved reading Iain’s piece on Bill Manhire published in Quote Unquote in 1996. Iain highlights Bill’s wit and ability to surprise, his humanity, humbleness, his lyricism, his cool. Iain writes: “When I was young, I wanted to write poems that sounded just like Bill’s: enigmatic, poised, deeply ironic, simultaneously lyrical and subversive. I never came within cooee of success.” I smiled in recognition. And yes, here I am bringing similar words to Iain’s sublime poetry. As Iain says in ‘The Poets’, the poem posted above, poetry can be such a blessing, a ‘wow’ unfolding.

Iain was writing poetry on his laptop, feeding on the nourishing strengths and blessings of poetry until his final days. Joy has included one of these poems, ‘Breakfast in Hamilton’ after her first pick. I have included one, ‘Blood Cancer Blues’, at the end of the tribute so that we may hold his voice close, gathering as we are here in this time of sadness, to read his poetry and share stories together. And yes, let’s embrace poetry as a blessing.

To celebrate the poetry of Iain Sharp and assemble a wee tribute, Poetry Shelf invited a few of Iain’s friends to select a favourite poem and write a few sentences. Donald Kerr has written a terrific tribute for The University of Otago that is a must read (go here). You can listen to Iain read here.

I offer a warm bouquet of sweet and salty ocean air from Te Henga to friends and family in this time of sadness, and especially to dear Joy. Thank you for helping create this special tribute.

the poems

Joy Sharp

The Reckoning

Life is improvised like Charlie Parker.

Sure, you can rehearse a few routines

but you never know in advance

how they’re likely to go down —

too rigid and they’re bound to snap

too loose and they won’t sustain

your weight or anyone’s interest.

Some nights nothing works

in spite of deft fingers

impeccable breathing

a wonderful shirt or hat.

Other nights are magical

but you can’t explain why

though you think hard for years . . .

like the beauty of your lover’s face

as she knelt to light a white candle

in Saint Patrick’s cathedral

the night you entered the church

only because it was raining.

In the end that’s what we’re left with . . .

shards of inexplicable magic

but while you’re waiting for them

instead of just pining for your brain

to become a rainbow or for the breaks

in every surface to heal, why don’t you

step outside and do something useful

such as extolling the stars?

Iain Sharp

The Singing Harp, Earl of Seacliff Art Workshop, 2004

This poem brings back a wonderful memory of the two of us dashing into the church seeking shelter from the rain. It was Iain’s poetry that drew me to him over 30 years ago, and poems like this will continue to sustain me. Iain was lovable, kind, intelligent, witty and fun to be with. We were blissfully happy living together in Nelson. He was my dearly-loved husband and my best friend. I miss him terribly but am grateful for his unwavering love and the life we shared.

Joy Sharp

Breakfast in Hamilton

Skittering along Clarence Street,

Hamilton, not long after dawn,

I’m feeling virtuous to be up

and walking and headed for

Pak ‘n’ Save for breakfast victuals

while back in our motel bed

my darling sleeps blithely on

and, having already completed

a circuit of Hamilton Lake,

my lumbago is easing up

and though the fierce morning glare

plays havoc with my ageing eyes

I’m congratulating myself

on my new athleticism

when I spy a big sign outside

the tax-reckoners which seems

to ask in comics sans serif:

“Are you praying too much?” —

and, taken aback, I wonder

“Can this be possible?

Is the universe ruled by

a god of limited patience

who wants us all to shut the eff up

so He can hear Himself

or She can hear Herself think?” —

like that moment this morning

when I heard by the sedges

the shrill peep-peep-peeping

of an adolescent pukeko

whose mother had had enough

of the incessant needfulness

and was dashing on tiptoe

to a remote part of the lake —

and then, pausing to rub my eyes,

I see the word in fact is “paying”

and, heck, I’m on the lowest rung

of middle-class remuneration

and en route to the supermarket,

so of course affirmative, of course,

but that other phantom question

gnaws at me still as I tote

yellow bags bulging with fruit

back to Ashwood Manor,

where Joy, just woken, requests

a cup of tea of decent strength—

and I pray for more days like this –

another skittering decade,

or half a decade at least,

with more dawns with Joy beside me,

more walks with most of myself

still more or less functional,

more encounters with pukeko,

more misread signage,

more libations of decent strength,

more Pak ‘n’ Save holiday breakfasts

in – for God’s sake – Hamilton

Iain Sharp

Serie Barford

THE NEVERTHELESS INCREDIBLY HAPPY POEM

Well, here it is at last, folks, the nevertheless

incredibly happy

poem, done in prose. Yes, happy. Remember? There might

be worms in the

apples, blood in the gutters, crumbs in the bed, cracks in

the globe,

black holes in the cosmos, guilt and acne and egg all over

our disgusting

faces, but things will work out, the end will be wholesome

heartwarming

fun for all the family, all creatures that on earth do

dwell chuckling

together and slapping their gleeful knees beneath a hunky-

dory sunset.

Trust me. Step down from your kitchen chair and return the

noose to your

bottom drawer. Throw away those toasted deathcap toad-

stool sandwiches.

Take the bullets from your pistol and the pistol from your

head. Smile.

Dance. Rouse your rump. Jive your jelly. Boogie your

booty. Flamenco

your flab. Immerse your caboodle in delirious optimism. A

new dawn is

coming. Summer is coming. The calvary is coming. The

millennium, apocalypse,

and Second Coming are coming. I know. I’ve had word right

from the top.

As I was traversing Albert Park after a few litres of

cognac with the

Earl of Seacliff, lo and behold, the deity peeked out from

behind a puff

of white cloud and spake unto me saying, “Hi there, Sharpie,

you daft

drunken bugger. Chin up, old son. Taller mercies are

beaming your way. Be

incredibly happy!”

Iain Sharp

The Globe Tapes Vol 1, 1985

I chose this poem from The Globe Tapes (Vol. 1), a collection of two booklets and two cassette tapes that recorded 42 poets who frequented Poetry Live at the Globe pub in Auckland, 1985. I vividly remember Iain reading this poem with his warm, distinctive voice cutting the smoke-filled room with a Glaswegian inflection and dramatic gestures. The Globe was run down but welcoming. Poets were rowdy and drawn from varied backgrounds. I visited The Globe several times before I garnered enough confidence to read a poem I’d written. I realised the stage was truly a public forum when a taxi driver rushed in one night, elbowed his way through the crowd and poured his heart out without using a microphone. He read a hastily jotted poem about his wife and memorable passengers, then charged back outside to his cab. Iain encouraged me to read that night. He always supported fledgling poets. Iain displayed an inquiring mind, a keen sense of humour, sarcasm toward ignorant and arrogant gatekeepers, gentleness and empathy toward the vulnerable. He was ‘a scholar and a gentleman’ in rumpled clothes with a big smile and will be missed by many.

Serie Barford

Gregory O’Brien

The Restoration

The sea coughs out

its bits of skeleton.

We put them back in.

There’s really no alternative.

We stand on the capstans

and throw bones

far into the harbour

while fog surrounds us

like a grey sigh.

Iain Sharp

For a few years, in the mid 1980s, Iain was a close friend and collaborator in various ventures, including the short-lived journal Rambling Jack (1986-7). Around the same time I was producing illustrations to accompany Iain’s column, ‘The Sharp End’, in New Outlook magazine. In his early 30s, Iain was firing on all cylinders. He was funny, noisy, bookish, and incredibly learned across a huge range of topics–yet it was also in his nature to be iconoclastic and acerbic. He really, really hated being bored–and if anyone crossed that line, he would get his back up. I remember the entire corpus of 19th century New Zealand poetry being given a serious take-down in his instantly notorious review of The New Place: Poetry of Settlement in New Zealand 1852-1914.

Iain was working as a librarian at the Epsom Training College Library, less than a kilometre from where I was living in a bedsitter. My friend Jane Coombs, Iain and I cooked up Rambling Jack together, with some input from Mark Williams,then residing in Hamilton. Iain’s poem ‘The Restoration’ was in the journal’s first issue; he took over as Editor-in-Chief for the second.

Joining Iain for morning coffee, en plein air, on the library steps, I would often be accompanied by my son (Rambling) Jack-Marcel, who was zero at the time. On good days the baby in the pram would sleep through the high-level literary discussion that was taking place around him.

One small thing I remember apropos of Iain and his inescapable Scottishness: Whenever Iain ran into Hone Tuwhare (and I witnessed this at least twice), Hone would come racing over to him and administer a serious hongi, with intensity and great feeling. The reason, Hone once elaborated, was that he and Iain both had the same Scottish ancestry (a fact Hone made quite something of). Iain was whanau and, accordingly, Hone’s greeting was the appropriate one.

I didn’t see Iain anywhere near as much as I would have liked after moving to Wellington at the end of that decade. I felt this as a loss. And now he is gone. Time rolls on. The baby in the pram (Jack-Marcel) turned 40 on Christmas eve. I’m left thinking how lucky we are when we fall into truly good company. Iain was certainly that. I’m left eagerly awaiting the publication of an expansive, miraculous, indispensible compendium of Iain Sharp’s poetry, short poetic prose-pieces and maybe some of his critical writing, collages and miscellanea.

Gregory O’Brien

Donald Kerr

Four o’clock. Five. The afternoon

slithers by on its broken ribs.

I linger awhile in city parks

wishing I’d learned the names of trees.

A woman who thinks I might want her

studies my palm in a coffee parlour.

Her words are swarms of winged insects

buzzing, buzzing beyond my grasp.

At Vulcan Lane a man I once knew

tells how his face has grown so heavy

He keeps falling forwards. I nod.

I buy him a shot of brandy.

The city is a huddle of oblongs.

Though I search for the hem of the sky

to lift the greyness from this life

there’s nothing my nails will go under.

Iain Sharp

published in Echoes 3, 1984.

“A lover of words and puzzles, he regularly tackled crossword puzzles, wordle, sudoku. He had an ability to remember weird facts and details on the strangest things. Indeed, his knowledge was encyclopaedic, and he was a very welcome team member on pub quiz nights. One fact needs mention: he was not showy, pompous, or arrogant with his learning. He was modest and quiet to the nth degree, exhibiting a demure reserve. Importantly, he was encouraging to others entering the literary world. New, younger poets, or older writers who wanted feedback on their works were met with the same patience and understanding and fairness.

The second and last items that feature in Real Gold concern Charles Heaphy (1820-1881), soldier, painter and colonial surveyor: ‘Plan of the town of Auckland’ (1851) and a pen and washing drawing of ‘Neche Cove, Nengone Loyalty Islands’ (c.1850). Heaphy obviously appealed to Iain’s sensibilities because in 2008 his Heaphy appeared, published by Auckland University Press. It is a superb biography that reflects his scholarship and his usual demand for accuracy in tracking down obscure facts about his subject. It is a very readable book. He must have been pleased with it.

Contemporaries in the world of letters in New Zealand have already remarked on this very sad occasion, the loss of such a good man: clever, witty, unassuming, never loud, and very kind. He was a consummate gentleman. His family will miss him greatly: Joy, his wife; Marion, his sister and her children Kyle and Rhiyen; and Don, Andrew and Tim, to whom Iain was a much-loved step-father. Vale.”

Donald Kerr, full tribute here

Dunedin, February 2026

Stephanie Johnson

Watching the Motorway by Moonlight

We sit on the viaduct

dangling our toes

in mid-air.

A truckload of turnips

heads towards Auckland

followed by

a carload of nuns

all eating hamburgers.

You close your eyes.

Your thoughts become

the night sky

the mist around the moon.

I nudge you gently.

Look love at the white moths.

An angel’s wing is moulting.

Iain Sharp

The Pierrot Variations (Hard Echo Press, 1985)

I chose this poem because Iain very kindly granted me the use of the first verse in my 2021 novel ‘Everything Changes’ and it brings him back to me. The character reading the poem asks himself ‘Did I ever the meet the poet? Was he the dapper young Scotsman?’ In the writing world, Iain was a rare bird – kind, gracious, erudite, humble, clever. We first met at the Globe in the early eighties. He was a poet the crowd hushed for, partly to listen to his lovely Scots accent but mostly to listen to his great poems. If only we could time travel back to those days and listen to him again.

Stephanie Johnson

Johanna Emeny

The Ponsonby Strut

First you go downtown and you get half-cut.

You climb College Hill when the taverns shut,

find an open party and talk some smut

or politics or art or God knows what.

Smoke in your eyes and cheap wine in your gut —

that’s how you do the Ponsonby Strut,

whoa-ho-ho the Ponsonby Strut (yeah).

Now here’s the hoop-la — the cast’s all present:

the drunks the punks, the poets, the peasants,

the incoherent, the incandescent,

the refugees from Boyle Crescent,

the drugged, the bugged, the insipid, the incessant,

the fresh-from-rehab semi-convalescent,

the unhappily unhugged, the plain unpleasant,

and Herman (the world’s oldest adolescent),

who boasts to his hosts he’s still tumescent.

There’s an implant down his urethra, but

it doesn’t impede the Ponsonby Strut,

whoa-ho-ho the Ponsonby Strut.

On the porch by the flowering quince

in fake black leather the Dark Prince

trills of his talent, tries to convince

Rhiannon with the raspberry rinse

that he’s the tastiest morsel since

lasagne added cheese to mince.

Rhi just yawns; the rest of us wince

beneath the moon’s wan aquatints.

Distant galleries lure us, but

we keep on doing the Ponsonby Strut,

whoa-ho-ho the Ponsonby Strut.

In the hall beneath the gilt chandelier

Hollywood Lorna strives to make it quite clear

she inhabits the wrong hemisphere.

She’s a born star, she says. Did you see her last year

in the outdoor production of King Lear?

But even while Lorna is bending your ear

Con, the red-nosed Trotskyite pamphleteer,

clutching fresh pamphlets attacks from the rear.

You look for a nook in which to disappear.

You just popped in, after all, for the beer

and whatever else you could souvenir.

The cost some evenings is too great, but

short of emigrating to Lower Hutt,

what else can you do but the Ponsonby Strut?

whoa-ho-ho the Ponsonby Strut.

Well, first you get sloshed as a halibut,

then swim up College Hill with your eyes half-shut.

Cursing yourself for being such a slut,

you crash another party and say God knows what.

Martian canals in your eyeballs, cardboard wine in your gut;

that’s how you do the Ponsonby Strut.

Iain Sharp

The Singing Harp

Only Iain Sharp could create such memorable characters as priapic Herman and amateur thespian Lorna in a poem constrained by only four end-rhyming sounds throughout.

“The Ponsonby Strut” swings along as jauntily and humorously as a local wag dishing the dirt on the area’s other inhabitants — “the drunks the punks, the poets, the peasants.” The language is naughty, taut, and clever. Who else would have thought to use “souvenir” as a verb?

In addition to being a gifted poet, Iain was always generously available to write a review or to help with research. He was a genuinely charming and beautifully mannered man. Beannachd leat, Iain.

Johanna Emeny

Anne Kennedy

WALKING THE inch arp WAY

A blue saxophone. A suggestion of cymbal. Doop-wah ffftt. Then a drum roll, a symphonic surge. inch arp walks down the road.

Yes, inch arp (dadaist) is walking down the road. Down the road walks arp. arp’s active. He’s proceeding. Talents must be nourished. Encouraged. A phantom crowd whistles and thumps.

arp trots. He nomadizes by. Compact. Authoritative. Stately, plump. Walking. Going public. In his tam o’shanter. In his eyebrows and wide trousers. With decorations to brighten the home.

He’s good at it. He’s holding his own. He knows what he’s about. He’s walking. Down. Great South Road. South of the equator. Penrose. Past dark fumes and smelly mills. Loving it. Loving the peripatetic method. Left foot right foot left. The most effective timing of the arms and legs has been a matter of controversy for some years. arp favours the two-beat crossover kick. Eyes front. Back straight. Sweep up from the hip with a relaxed lower leg and ankle

Dugongs must have flippers. Ducks have rubber webs. Frogs leap high and frogs leap low. arp walks. He walks down the road. That’s what ‘staying on the ball’ is.

Describe him. Describe his walk. Describe the angles his teeth make relative to his spinal curvature. Cite the latitude of the street. The composition of the asphalt. The height of the kerbstones above sea-level in centimetres. The distance from Mercury. Io. The nearest civilized star. What proportion of arp’s soles have been worn away by friction? How many molecules does he contain? How many parasites? List any perceptual problems, clinical manifestations, minor neurological signs. Comment on the isobars. The aphasiological context. If you were the government of the day how would you improve this scene?

The road is being walked down by arp. It feels his impress. Steady, inch. Don’t get overexcited. Remember the day in the freightyard.

inch ambles. He paces himself. He’s a flexible mover. Agile. Awake. Coming back from the market. Collecting visual information.

That outline’s the Bombay Hills. The ocean must be out there too. Somewhere. Distant buoys and lightships blinking. Left foot right foot. Look before crossing. Look up when you can. Bits of sky, whole stretches, cold and pure as white chrysanthemum. Nascent shimmers near the horizon. 350 A.D. The Pope invents Christmas. 1986. arp’s walk. Doop-wah. Wah-doop. ffftt.

Iain Sharp

First appeared: Rambling Jack 2 (Miracle Mart Receiving, 1986)

This was, I think, the first piece of creative writing I read by polymath Iain Sharp – who I already knew from his daring writing on books and literature. I remember being dazzled. Forty years later, I still love this flash-fiction, am amazed by its inventiveness, humour and – no other word – profundity. And importantly its relevance to today.

I remember a bit of background about this piece, from bumping into Iain and his future wife Joy – who were a picture of happiness – in cafes in Auckland. As people who knew Iain will know, he maintained his lovely Scottish accent, and therefore (I guess) noticed New Zealand accents. To his ear, people around him pronounced his name, ‘Inch Arp’.

The flash-fiction ‘Walking the inch arp way’ packs so many things into its economical form, riffing and extemporizing like Jazz. First of all, of course, it calls on the Dadaist artist and poet, Jean Arp, who I seem to recall was having a bit of a resurgence in the 80s. (Or was that just in cafes in Auckland?) Like Dadaism, Iain’s poem is absurd and aching at the same time. Hilarious and political. The speaker, inch arp, navigates the world with both puffery (‘a drum-roll, a symphonic surge’) and self-deprecation (‘arp trots’), in itself a kind of loping gait. Sharp finds myriad connections between the self and everything-else – from the body (‘his eyebrows and wide trousers’), to animals, to outer space. In so few words, Sharp drills down through ‘dark fumes and smelly mills’, ‘the freightyard’, bureaucracy-speak to find an underlying dystopia. ‘If you were the government of the day how would you improve this scene?’

Like Jazz, Iain’s attuned ear makes ‘Walking the inch arp way’ sound so good. The vowel chimings, the found phrases, the rhythmic walk. In the end, the beautiful juxtapositions of tossed-offness and refinement carry us along while we absorb a representation of being.

Thank goodness we have Iain’s legacy of writing.

My deep condolences to Joy and Iain’s wider family.

RIP Iain Sharp.

Anne Kennedy

Ian Wedde

The Ian Sharp Poem

Iain Sharp is a fat parcel

of mixed groceries

tied with a clumsy knot.

Iain Sharp is a black kite

adrift on changeable winds.

Iain Sharp is a pile of scoria

drifting softly to the sea.

Whenever I peep in mirrors

Iain Sharp frowns back at me.

It’s terrifying.

Iain Sharp is a runaway tramcar.

Iain Sharp is a chunk of moonrock.

Iain Sharp is nine letters wrenched

from the Roman Alphabet.

Look there and there!

Bits of bright confetti blow

from chapel to chapel.

I chase them with outstretched hands.

They might be Iain Sharp.

Iain Sharp

Yes it was heartbreaking to hear of Iain’s death. I loved his wry, self-effacing tone, picking an example results in protracted indecision! One of my favourites is given away by its droll title, it’s ‘The Iain Sharp Poem By Iain Sharp’. So many fleeting moments that yet convey an observant, genuine sensibility, and perhaps an invitation.

Ian Wedde

Blood Cancer Blues

When mild anaemia

becomes leukaemia

that’s not good news.

Blood cancer blues.

Though some last for years

with cells shaped like tears,

you don’t get to choose.

Blood cancer blues.

Quite at ease, then whup!

Someone’s number’s up,

but precisely whose?

Blood cancer blues.

Leaving my sweet life

and my lovely wife

and our ocean views.

Blood cancer blues.

Watching the sun sink

peach and coraline pink,

cerise and chartreuse.

Blood cancer blues.

Let me apprehend

blessings till the end

amidst darker hues.

Blood cancer blues.

Iain Sharp