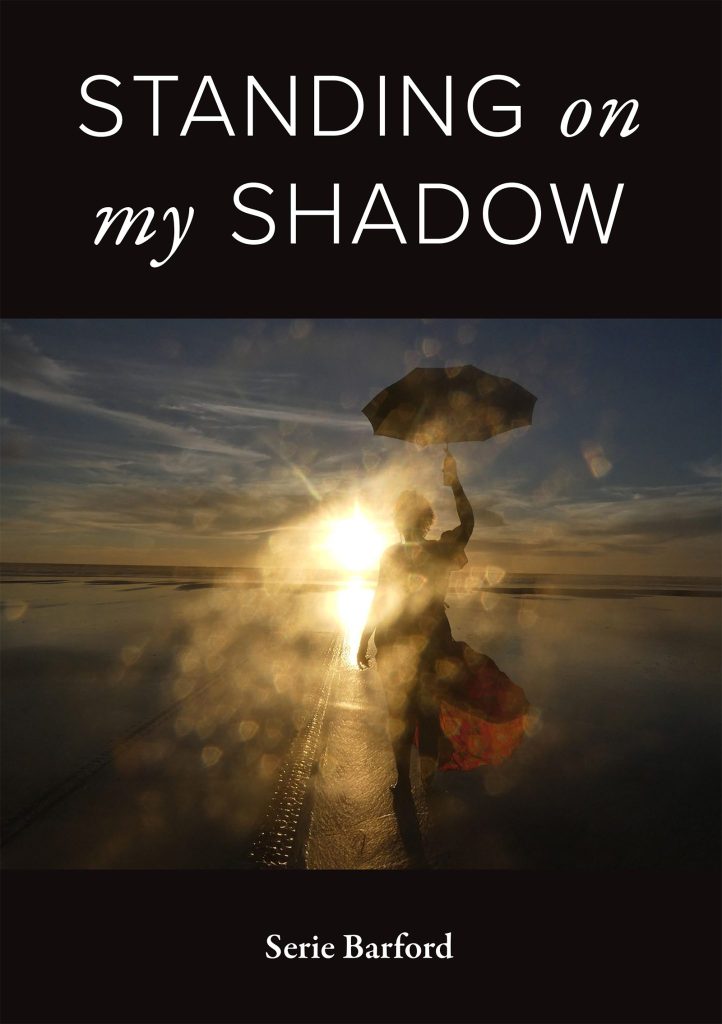

STANDING on my SHADOW by Serie Barford

Anahera Press, 2025

Serie Barford and I have been travelling cancer roads for a number of years, so to both have poetry collections out this year resonates deeply. Especially when 2025 has been challenging for both of us, and especially when Serie is now in hospice care, knowing this may be her last summer. I hold this sad news to my heart. We all do – friends, our poetry communities, family.

I have been rereading Serie’s book over the past fortnight in the gaps of appointments. Writing down single words and phrases in my notebook. Musing on how poetry, whether we write or read it, can be so nourishing, so connecting.

Serie’s collection is divided into five parts, offering poetry that is embedded in the somersault effect on body and mind when navigating cancer. She is standing on the rim and guts and wings of all kinds of shadows. Think death. Think life. Think uncertainty. Think aroha.

The opening section, ‘The Exclusion Zone’, draws us to the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone in Ukraine, where there are signs of rejuvenation in the devastation. The first poem, ‘Picture this’, does exactly that, invites us to picture the scene. It is physical, it is elsewhere, on the the other side of the world, with ‘a blue wooden church’, with flowers tumbling from hanging baskets, Sisters of Mercy feeding the hungry. And the poet is asking us to picture her with her notebooks of cancer jottings. And then the final stanza. This is it. This is a poetry collection where the physical detail of the world, whether at home or away, is luminous. Where all senses operate under a heightened awareness, reminding us that tough health diagnoses sometimes intensify what is important, what offers bridges to joy and delight. Here is the final couplet:

Picture sun on my face. A cobbled street. An outside

table. Glistening red borscht for lunch. Delight.

In the next poem, ‘Chornobyl Cinderella’, an abandoned shoe is spotted, a shoe that is a repository for story, for unbearable loss and tragedy, and it feels like our lives are peppered with abandoned shoes, with narratives that arrive in wisps and slants. The what is not said and can never be said alongside the what is said and must be said. The kind of border a poet might struggle with as she writes poetry out of an experience that is sometimes unspeakable.

I begin with the exclusion zone. I picture the exclusion zone, and it is both Chornoble and a personal experience. It is precious life and it is precarious life. Ah, how I connect with this book. In the second section, ‘Bitter chalice’, the physical detail of the world is still vital, as the poet goes to Building 8 for chemotherapy, as she deciphers percentages and oncology talk.

The writing draws upon light as much as dark, mapping bridges between tenderness and toxicity. Think the toxicity of nuclear waster echoing through the toxic impact of chemotherapy upon body and mind. Think tatau on the skin of others, connecting generations, ancestors, mana. Think the poet’s uninked skin now bearing the tattooed dot associated with radiotherapy. Think the tapu head and hair, the missing hair, the woman donating hair, the hair now silver.

Picture this. Imagine this. Feel this.

The fifth section draws us to ‘The green line’. The title poem follows the hospital’s green line to get to Radiology, but the collection offers us a weave of green lines. We might move from the Ukraine to Tāmaki Makaurau, moving from a stretched health system to alternative therapies, from the coordinates of cancer to the coordinates of whanau. The mother prepares breakfast esi. The grandmother dries esi seeds. The mother nudging her family to eat well. Here from ‘Eating esi’:

Mum nudges Dad: You too. East esi. Get well. Stay well.

Don’t die before me. Don’t you dare!

Follow the green line and you are following a voice sensitive to the contours of illness, to the jags and spikes and science of health challenges, to the experience of the patient next to her. She is both speaking and writing, busting the exclusion zone, her words lithe on the line, inked with angels anxiety grace. This from ‘Egyptian ink’:

Same old same old.

Chemotherapy is this century’s Egyptian ointment.

A spin on arsenic paste.

Black ink pools on papyrus.

Here and there

the vomiting mouth.

The final word of the collection is ‘aroha’. The final image drawing us back to the infusion of toxicity and delight we picture at the start of the collection. Here I am, personally attached to this personal record of an utterly challenging time, and I am brimming with sadness and recognition, joy and connections. Read the final paragraph from ‘The grace of a stranger’, order this book, and gift it to a friend.

Yesterday I was miserable. Overwhelmed by side effects.

Lay on the floor, heart flailing, sunlight rippling through

French doors, guarded by anxious cats. Birds were singing.

Clocks ticking. I thought about Chornobyl, the Exclusion

Zone, the trumpeting angel memorial to lives lost. Waited

for ancestors to appear. Fetch me. But it wasn’t my time.

Today I’m visiting an oncologist in Building 8. Facing this

tricky business of living. Talking about celestial beings.

Feeling uplifted by the grace of a stranger.

Aroha.

Serie Barford was born in Aotearoa to a German-Samoan mother and a Palagi father. She is one of New Zealand’s leading voices in contemporary poetry and has been a pioneer for Pasifika women poets since the late 1970s. She has published five previous collections of poetry. Sleeping with Stones was shortlisted for the 2022 Ockham New Zealand Book Award for Poetry. She was a recipient of a 2018 Pasifika residency at the Michael King Writers Centre. Serie promoted a Ukrainian translation of her poetry collection Tapa Talk at an international book festival in Kiev in 2019.

Anahera Press page

Serie in conversation with Emile Donovan on RNZ

Serie selects some books at The Spin Off

Sophie van Waardenberg review at Aotearoa NZ Review of Books

Hebe Kearney review at Kete Books

k