AUP New Poets 11: Xiaole Zhan, Margo Montes de Oca, J. A. Vili

editor Anne Kennedy, Auckland University Press, 2025

The AUP New Poet series has launched the careers of many poets, consistently showcasing the depth and breadth of poetry in Aoteraoa. Editor Anne Kennedy has drawn together three distinctive writers, whether in view of style, form or subject matter, yet there are also vital connections. For example, the poets – Xiaole Zhan, Margo Montes de Oca and J. A. Vili – acknowledge a history of poetry reading, referencing writers that have nurtured and inspired them. There are recurrent anchors in memory, experience, ideas, politics, the personal, everyday contexts. Above all, there is the contagious transmission of joy. Whether I am entering fields of pain, grief, wonder or philosophy, I am experiencing joy as I read. Absolute delight in what poetry can do.

I have reviewed each section, and followed that with a reading and conversation with each poet.

Auckland University press page

63.

In the drench, there is a room where my Pākeha grandfather waits beside

an upright piano covered in dust. His eyes are milky with illness. Lucius

Seneca crouches in the corner, wheezing in and out. The piano has outlived

the axe, and the tree, and both men in the room. Like the word heaven.

Xiaole Zhan

from Arcadiana

Xiaole Zhan’s hybrid sequence, Arcadiana, resembles an album of navigations; writing that can be claimed as essay, poetry, memoir, prose . . . a suite of cross fertilisations. At its heart, and yes this is a sequence with heart, is the magnetic pull of storytelling. Why do stories matter to us? Does poetry matter?

I want to share some of my readings avenues through ‘Arcadiana’ in order to offer a taste of my delight. I often flag poetry that moves me, but what do I mean by ‘move’? For me to be be moved as a poetry reader encompasses multiple movements, maybe like a sonata might move mind, heart and body. It’s intake of breath and goosebump skin. So yes, I am intensely and wonderfully moved by Arcadiana’.

Xiaole is exploring their memory chambers, hunting out piquant and personal detail that sticks, sometimes unsettling, detail that sets them musing. It’s sights and smells and sounds; it’s childhood and healing strength. It is a storehouse of stories, most especially the thorny depository in the Bible, with its violence, horrors and miracles. Just like fairytales. The cruel Pakehā grandfather, the nasty Pakehā stepfather, reading to the young child. It’s the strengthening mother.

Philosophical threads captivate my hunger for ideas, especially in the open field of storytelling, especially as we navigate lies and belief, how to advance and enhance what we tell. How we might fall upon mourning in music, and music in mourning. This metonymic rubbing, this idea against that experience, that experience against this idea. Ah. The citations from key thinkers/writers, in keeping with the mode of essayist, enriching links to history, culture, intellectual thought, personal experience. And in this open field, reading and writing are both forms of listening.

I love how moisture, drench and stormwater are a recurring motif or theme. I find myself exploring the collection in view of its moistness, whether sweet dew or slam of flood. Colonisation. Racism. I soak up a poem’s reach and possibilities. I discover ‘Arcadiana Op. 12’, is a 1994 composition for string quartet written by the English composer Thomas Adès, with both water and land movements, haunting violin. And here we are full circle. Back to movement. Steeped in poetry joy. I won’t forget this reading for ages.

& the window is open – enough for some sky to spill inwards

with a coolness that flows over my arms

and Ru beside me who murmurs and sighs,

his closed eyes half-moons in the pillow-dark.

The more I remember time the more I press my face to the glass of it

the more the outside world seems to vibrate with memory

of its own. It whispers through the window’s mouth &

in a language I half-understand says look,

Margo Montes de Oca

from ‘omens’

As the title suggests, Margo Montes de Oca‘s collection of poems, intertidal, is also a series of movements, but the movement carries you along different currents. Before I started reading, I pondered on the constitution of an intertidal zone, on the idea of ebb and flow, deposit and removal. And then, when I was immersed in the poetry, the first word I jotted down was joy. I felt an incredible brightness, a joy in the natural world, the beach and the river, as the poems embraced sea, time, dream, light, breath, drift, sky.

The physicality of the poems resembles visual buds, detail that opens out a vivid scene, and place simply glows into existence. This is my first love. My second love is the way Margo’s poetry embodies notions of braid, entirely fitting in an intertidal zone. She uses a variety of poetic forms. For example, the poem ‘bajo la luna, un caballo de noche’, is a glosa, a form that braids borrowed lines with the poet’s, in this example Louise Glück (you can hear this poem below). Margo tests out Natalie Linh Bolderston’s invented poetic form, ‘a germination’. Twelve small triplets on the page like a baker’s dozen, poetic buds as much as braids, as the visual layout propels my physical reading in myriad directions. My eyes darting as the poem catches proximity and distance, Mexico and Aotearoa, arrival and farewell, land and light. An intertidal zone. Glorious.

There are also language braids: Spanish nestling alongside English with their different musicalities and heritage, the language of sky, ocean, world, the language of breath . . . all linked to an impulse to read, a compulsion to read the drift of sea or river or cloud. And more than anything, above all, so haunting and evocative, is the braid between ebb and flow, the polyvalent gap. We reach the open window through which the sky spills, the crevice in the floorboards through which the speaker may fall, the fertile gap/movement/bud between today tomorrow, together apart, awake asleep.

A number of poems are written ‘after’ or dedicated to a muse (H. D., Sappho, Louise Glück, Alice Oswald, Virginia Woolf) and again we enter an intertidal zone, because, in a way, we are all reading and writing after the poetry that precedes us, that inspires and nourishes. In reading Margo’s collection, I am ‘setting off into quiet drift’, the poems drawing me deep into the understated and the shadow figures, a mesmeric physicality, the way poetry can be both bud and braid. Glorious.

But I am carved in thought

My tongue is kauri

My eyes are shells

My heart is stone

In a graveyard sowed with death

I am captured –

by how full of life

the weeds are.

J. A. Vili

from ‘Your Tangi’

What I love about AUP New Poets 11, is way the anthology promotes new poetry as many things. There is zero attachment to the formulaic because the poetry stretches possibilities in view of voice, form, mind and heart. The final poet, V. A. Vili, draws us deep into poetry as ache in his chapbook, Poems Lost During the Void. Many of the poems are dedicated to friends and family, and many of the poems depend upon a bloodline of grief and loss. It is personal and it is poignant. In Vili’s bio, we read that the poet has dedicated some of the poems to his children whose mother died when they were young.

I feel like I am entering a precious clearing, a space for both poet and reader to grieve, to stall upon casket, graveyard, ashes, tangi, mourning; to travel in memory fields and draw closer to the missed and the missing. To reflect and retrieve and perhaps nourish self and loved ones.

Yet this poetic space for mourning is not held at a distance. It is embedded in everyday life and memory, it belongs to particular times and places, where someone dons Karen Walker glasses, wears Chucks, watches rugby league, drinks L & P, listens to ‘Back in Black’, gifts a zodiac oa. We read in the opening poem, ‘Funding Cuts Deep’, of these ‘torrent times’ and that ‘the tūī sings in protest’. We are in the rip and tear of the present. One poem features a chess game, where the moves are tough, and the queen is lost, but where checkmate becomes ‘check on you, mate’, and that is unbearably touching. Poetry itself matters. Reading matters. Going to libraries. Reading Robert Sullivan and Carole Ann Duffy and Thomas Kinsella. Poetry is invested in relationships, making multiple appearances.

Viti’s poems are infused with grief and you carry that with you as you read, but they also, and most importantly, radiats life. The final poem, ‘Your Tangi’, dedicated to his tamariki, so nuanced, so fluent in its telling, is the most moving poem I have read in age (you can hear Viiti read it below). If poems are lost in the void of grief, poems are also recovered, restored, and replenished in the passages of living, in vital relationships with friends and family to whom these poems are dedicated. If we keep asking why poetry matters, herein is an answer, poetry is a lifeline, a love-line, a gift. A taonga.

This anthology makes me want to keep reading and reviewing and writing poetry. A gift indeed.

Xiaole Zhan

Xiaole reads an excerpt from ‘Arcadiana’

Were there any highlights, epiphanies, discoveries, challenges as you wrote this collection?

I began writing Arcadiana with the questions of ‘what is a story?’, and ‘what does a story matter?’ My childhood in a Chinese-Pakeha family, as with many childhoods, perhaps all childhoods when recalled in memory, was one in which the line between myths, stories, secrets and lies were hazy.

Many of the stories I grew up with might be called secrets, or lies—I believed as a child I was a blood descendant of Captain Cook, who I was told was a great explorer and a distant relative of my Pakeha grandmother. My late Chinese father, who was abusive, was kept a secret from me until I accidentally found a photo of him in my aunt’s drawer as a teenager.

I recall in Arcadiana, too, the memory of my mother, when I was fourteen or so, arranging for me to teach Sunday school at the local church where I took piano lessons. I had never attended Sunday school myself; we were not a religious family. When I brought this up as a possible issue, my mother said to me, 宝贝, Darling, it doesn’t matter. Even now, my mother doesn’t see anything particularly grave nor comical about this arrangement. I learnt then: stories and lies mean different things to my mother and to me.

The line between a lie and a story shifts across cultures; it’s common for Chinese families to withhold things like sickness and death from children, or from the sick and dying themselves, until the very last moment, or even indefinitely. Perhaps a lie matters less within a culture where allegiance to family, to holistic social ties, comes before allegiance to individual truth. Perhaps bearing an uncomfortable truth in secret is a burden of love; perhaps being told a lie is being spared.

The line between life and death is blurry, mediated through the haze of health. The line between myth and reality is also blurry, mediated through the haze of memory. I am interested in how language allows us to be submerged in the haziest of boundaries.

What matters when you are writing a poem? Or to rephrase, what do you want your poetry to do?

As a child, I remember running to my mother with a finished story, seeing her nod at words she didn’t understand, and then watching her carry on with washing the dishes. I can’t help but feel now that a story matters less in a childhood where meals were eaten steaming hot and dishes were washed by my mother’s callused hands. My popo, too, never learnt to read or write, or to speak in Mandarin. What does a story matter in the wake of a grandmother speaking in Cantonese to a granddaughter who no longer understands the language?

I remember telling my mother over the phone the other day about an event where I had been invited to share a bit about my life as a guest speaker. A little later in the call she said to me, matter-of-factly, she feels as if she doesn’t have any major achievements in life, that she only has her children. Nervousness for a public speech matters less in the realisation that my mother has led the life more worthy of being shared upon that stage: that her vastness of personhood is as deserving and devastating as anyone else’s.

One of J.A. Vili’s poems in this collection comes to mind, one that I have returned to often, ‘Mother’s Rope’. I admire how Vili’s poems feel as living and breathing as people. Indeed, he describes his children as his “greatest poems”. I realise more and more that what keeps me most tethered to life isn’t art or poetry or beauty or even hope, but people — mothers and loved ones.

I feel as if I’ve answered this question backwards. Perhaps what I’m trying to say is: I find a lot of meaning in allowing things to matter less in the wake of the already-monumental stakes of living, of staying alive, of doing the dishes, of calling mothers, of worrying over daughters, from moment to moment — in the wake of the vastness of other people. So, at the moment, it makes the most sense for me to write from this place of — and I’m not so sure what the right word is here — perhaps, humility — or, perhaps, astonishment — for people, and for life itself.

Are there particular poets that have sustained you, as you navigate poetry as both reader and writer?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this poem by Polish poet Wisława Szymborska, A Word on Statistics. I love that it’s funny, a kind of ironic character study of all of humanity. But I also repeat certain lines to myself, like how out of 100 people, those that are “Worthy of empathy” are “ninety-nine”, even if more than half are “Harmless alone,// turning savage in crowds”. I confess — I often feel ninety-nine is far too high a number! But I’m finding it more and more difficult to condemn individuals—the way I often condemned others confidently, even a year or two ago—living among people, especially family, who are often difficult, most of whom would be ‘cancelled’ for one reason or another if they shared their thoughts publicly. I feel interested in Szymborska’s empathy, in most people being deserving of empathy (perhaps even 99 of 100!), and how empathy is neither condemnation nor absolution, but, perhaps, attention to how every person is irreducible, how condemnation or absolution is always an inadequate shorthand for personhood.

We are living in hazardous and ruinous times. Can you name three things that give you joy and hope?

I have to turn our attention here to Palestinian relief funds, such as the Palestine Children’s Relief Fund. The Palestine Toolkit is also a helpful tool for guidance in taking concrete actions, but each city and locale will have their own communities and targeted action points.

I say I find it more and more difficult to condemn individuals, but when it comes to large-scale systemic violence—such as Israel’s ongoing genocide of Palestinians, and its long history of violent settler colonialism—there is no choice but to condemn these structures as individuals who hope to form a more humane community. The alternative is what forms and sustains structures of systemic violence. There is no choice but to take concrete actions—donating to relief funds, or buying an e-sim, or writing to local MPs, or attending and aiding community protests—these actions give me hope.

Xiaole Zhan (詹小乐) is a Chinese-Aotearoa writer and composer based in Naarm. They are the recipient of a 2025 Red Room Poetry Fellowship, the 2024 Kat Muscat Fellowship. They were also the winner of the 2023 Kill Your Darlings Non-Fiction Prize for their essay-memoir ‘Think An Empty Room, Moonly With Phoneglow’ exploring experiences of racism growing up in a mixed Pākehā-Chinese family, and the winner of the 2023 Charles Brasch Young Writers Essay Competition for their essay ‘Muscle Memory’ exploring music, depression, queerness, and gender discrimination over time. Their name in Chinese is 小乐 and means ‘Little Happy’ but can also be read as ‘Little Music’.

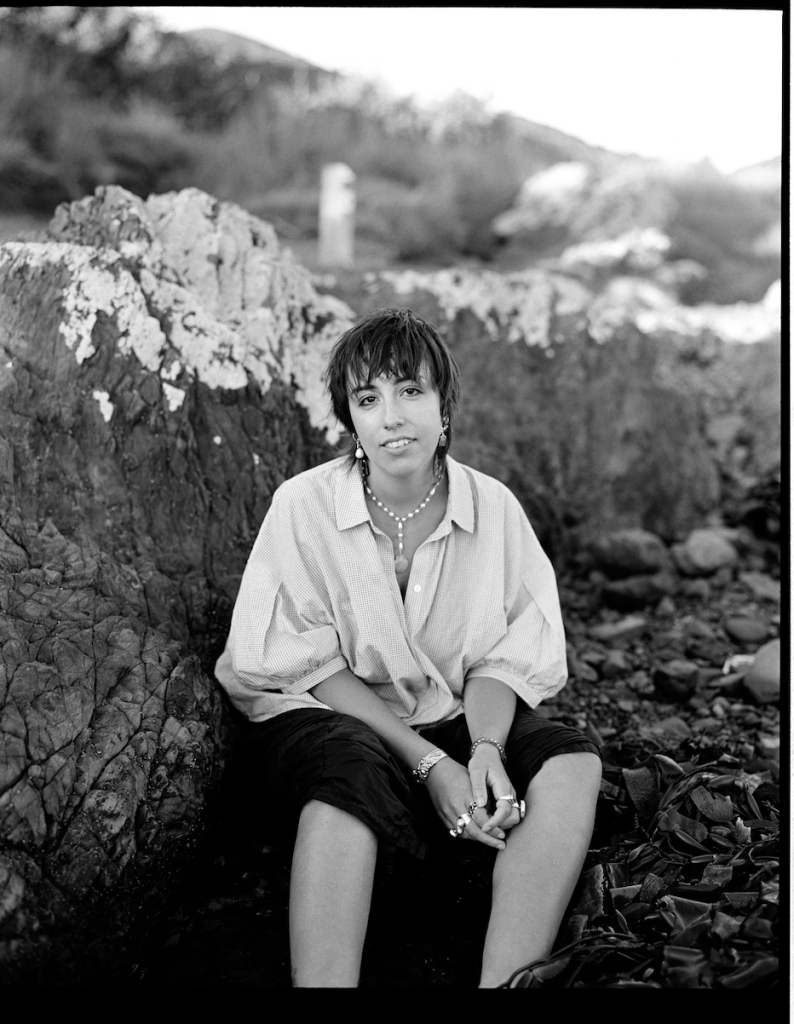

Margo Montes de Oca

Photo credit: Harry Culy

‘Metamorphic’

‘Tuatoru Street’

‘bajo la luna, un caballo de noche’

Were there any highlights, epiphanies, discoveries, challenges as you wrote this collection?

For a while it was hard to write enough poems to fill the gaps in the chapbook. I discovered that a good way to catalyse a poem was to respond to existing work, or to find a form which allowed me to engage with other poems I loved, so that writing felt more like an experimental conversation than a solitary exercise. My favourite form-discoveries were the golden shovel, the glosa, and the germination.

What matters when you are writing a poem? Or to rephrase, what do you want your poetry to do?

I like Anne Carson’s suggestion that ‘to make a mental space memorable, you put into it movement, light and unexpectedness’. I think maybe these things are what I try to put into my poems. I like poems that feel honest about the extent to which our memories or experiences are porous, unpredictable, and shaped by our interactions with everything around us. I also like poems that feel ghosted by something – like writing about the natural that’s ghosted by the preternatural, present ghosted by future or past, thought ghosted by dream. Poetry has a dreamlike intensity and resonance which allows us to reimagine our relationship to time and the non-human. I would like to think that my poems carry some dream-residue.

Are there particular poets that have sustained you, as you navigate poetry as both reader and writer?

(Preter)natural poets like Alice Oswald, Ted Hughes, W.B Yeats, H.D., Elizabeth Bishop. Mexican poets like Amparo Dávila and Homero Aridjis. Local poets like Alison Glenny, Anna Jackson, and Dani Yourukova. Most especially two of my best friends in the world, who have introduced me to so much writing and also happen to be my favourite poets, Loretta Riach and Ruben Mita.

We are living in hazardous and ruinous times. Can you name three things that give you joy and hope?

Being outside, in particular swimming in the sea (my favourite beach is Princess Bay on Wellington’s south coast), or even better being outside with friends or family. It is one of the most important things I can do to remind myself of what’s real around me and of what is worth protecting — that is, people and place. Going to protests. Eating food cooked by my dad.

Margo Montes de Oca is a poet and researcher of Mexican and Pākehā descent, living in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. She holds degrees in English Literature and in Ecology and Biodiversity from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington. She was a 2024 Starling writer-in-residence at the New Zealand Young Writers Festival, and her poetry has been published in journals like Starling, Sweet Mammalian, Min-a-rets, Turbine | Kapohau and Mayhem Journal. Her debut chapbook, ‘intertidal’, can be found in AUP New Poets 11 (AUP 2025).

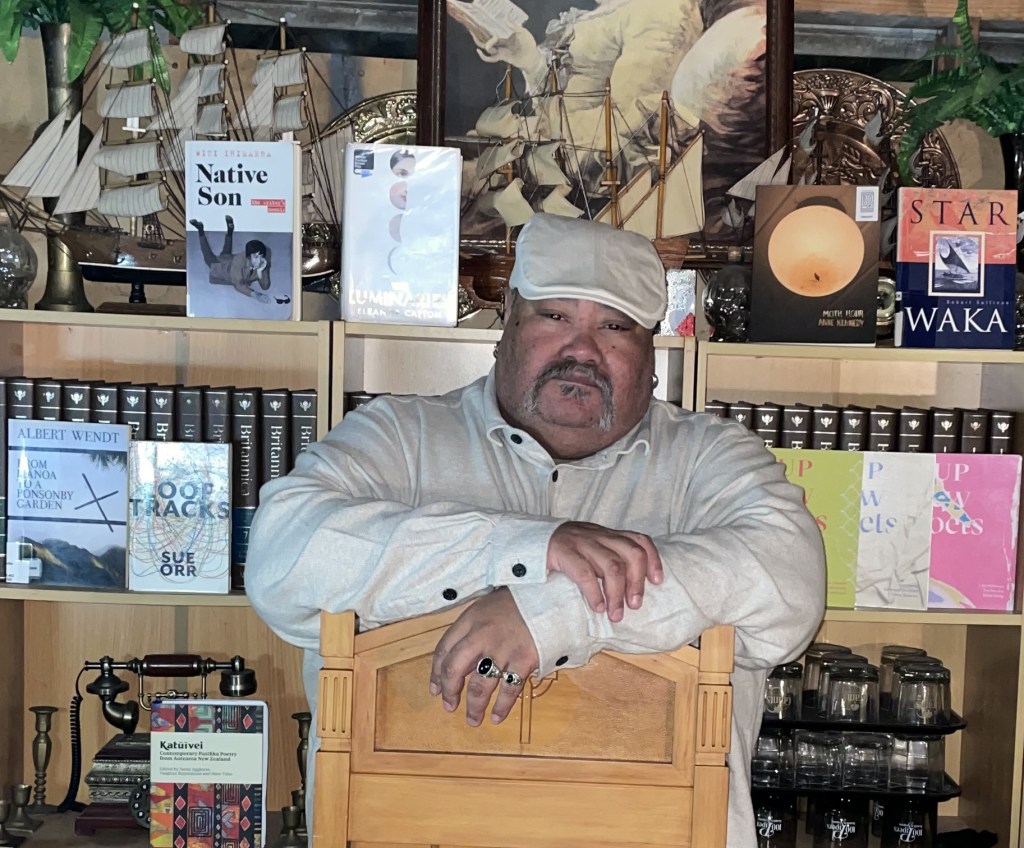

J. A. Vili

‘Sleeping with Bats’

‘Tobruck Road’

‘Your Tangi’

Were there any highlights, epiphanies, discoveries, challenges as you wrote this collection?

A big highlight was that I didn’t rhyme, not even once. I can laugh at it now, but I would have been a great rapper or song writer. I also finally grasped that I had to stop thinking and writing inside my head, just wasting words in a mental space and just to let my pen touch the page. I found out then, that it just starts to move by itself and the verses start flowing. There were two poems I found challenging and decided to leave out. The first was about a child with a terminal illness, which I will attempt to write a children’s book on. The other was about the Mount Wellington Panmure RSA tragedy that occurred in my community, I just couldn’t break the wall for that one. There is a 25-year gap between my poetry, so I thought about what I had achieved during that time and my children were the only thing that mattered. And for what I had lost, well that’s where departed family, friends and “Poems Lost During The Void,” came about.

Someone told me after reading my poems in this collection, “So, you talk to dead people.” I found that quite amusing. I realised it’s plain for people to see that I do, but I’m in a moment of reminisce, just writing poetry freely with no nuance of subjects being alive or not. This was a paradox to me and I wanted to find an answer to try and explain it, and that’s where the epiphany comes into it. It’s like a soldier at war, writing letters home to their loved ones. Telling them how much they missed them, promising them that they will make it back to them. I don’t know if it was memory, or just how I feel about their loss, but it is the answer that best describes why I write, the way I write poems for them. If I was to crossover tomorrow, I would see my old family and friends come to greet me and their first words out of their mouths were, “Welcome home poet(soldier), we got your poems(letters),” and that gives me a sense of peace, like death is just catching up with old friends.

What matters when you are writing a poem? Or to rephrase, what do you want your poetry to do?

I was a teenager when I wrote my first poem which was about a friend’s suicide. The teacher never read it out to the class, like she did the others. I don’t want any poem or subject stifled or put to the bottom of a pile due to one person’s opinion, I want it to be read or heard first before judgement. I started writing again after all these years to console my children over their mother’s death and to give them memories of her. Then I started writing and gifting poems to family and friends at funerals. My poems were never meant to be public, as I always threw them into graves, but due to my friends’ death in his 40’s, my advocacy for suicide prevention reignited and I started selling my poems for gold coins to fundraise for the charities. I want my poems to comfort my children, make them laugh, question and dissect this other side of their father. Also, that maybe the experiences I write about can resonate with others to find a glimmer of light from their loss and grief, or to remember their own fond memories of their departed. That is what I want most from this collection of poetry.

Are there particular poets that have sustained you, as you navigate poetry as both reader and writer?

For some naïve reason (probably the years away from poetry), I thought that maybe if I went to writing school and graduated, I could call myself a true poet, not realising I had become one in my teens, just with no life experience. I was always immersed in old poets in my youth, but it was the wealth of NZ poets that caught me by surprise when I returned to school later on in life. I have always had a fondness for my teachers, all the way back to Primary School, especially English. I may seem biased in my choice, but I have continued learning from them, even a decade after graduation, through their books. I read Anne Kennedy’s Moth Hour last year and that was a wonderful respite from my own writing and contemplating another poet’s tribute to their loved one’s passing was a continuation of the healing process poetry can have. It was revitalizing. Over the new year, I read Robert Sullivan’s Hopurangi – Songcatcher: Poems From The Maramataka. If you were taking a walk together listening to him recite his book, you would not have realized you just walked over a mountain, across a beach and into his garden, as if his words had carried you along the journey. What better textbooks do I need and who better to learn from. These two poets also encouraged me not to quit and to submit my work, so I am grateful for that.

We are living in hazardous and ruinous times. Can you name three things that give you joy and hope?

My children making it through adolescence, becoming young adults and then watching them have children. I truly believe that grandchildren are your second chance to make up for your parental mistakes and bring you even closer to your children later on in life. Things that can’t be forgotten can always be forgiven and I find solace in that and the future looks far more kinder through them.

I am in awe of NZ poetry and writing. The old bards still trailblazing and the young amazing talent coming out from the biggest cities and smallest of towns. The ever-changing voices of the poetic landscape gives me a great sense of pride and I would be quite happy to read only NZ poetry for the rest of my life. That’s what I did during the lockdowns, in books and online, from a school boy to the NZ Poet Laureat, from a farm girl to a MNZM recipient. It was a truly awesome lockdown for me to discover all these special voices, who I know have made a difference in this world.

Aotearoa is a melting pot of culture, especially in Auckland and it is great to have all these ethnic celebrations to experience. The Pasifika Festival is back on with vibrant noise and the food is a celebration in itself, along with the many cultural and fine food festivals around the country. Matariki is a chance to visit local attractions and vistas. Polyfest is still going strong, the Chinese New Year festivities are a spectacle and I still want to experience my first Holi festival. I never seem to miss St Patrick’s Day though, being fellow “Islanders,” and all, even if I’m just celebrating at home. My grass is green.

J. A. Vili is an Auckland-based poet of Samoan descent whose

poetry often advocates for suicide prevention and mental illness

support. He dedicates poems to friends and to his children who lost

their mother at a young age. Vili holds a bachelor of creative

writing. His poems have appeared in Ika journal and Katūīvei:

Contemporary Pasifika Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand (Massey

University Press, 2024).

Pingback: Poetry Shelf celebrates The Venetian Blind Poems with a collage conversation with nine poets | NZ Poetry Shelf