To celebrate the four collections on the Ockham NZ Book Award Poetry Short list I invited the poets to answer a handful of questions.

Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit, Emma Neale, Otago University Press, 2024

I want to hold this morning

under an agapanthus sky

with a gentle, moth-eyed horse

as if the thread of language

could ever weave a hide

against the hook and ache of loss

when we carry it

deep as the mare carries

the sprint, the vault,

in her hocks, her fetlocks.

Emma Neale

from ‘The Moth-eyed Steeplechase Horse’

Poetry grows out of both experience and imaginings, with truth and lies active in both realms. Lately, I have been musing upon and indeed bolstered by the way poetry is fed and watered within community gardens. A hub of vital connections. I have read Emma Neale’s Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit three times and it is the kind of book I want to have a long slow cafe conversation with you over coffee and pain au chocolat. This is a book born out of experience, out of truth and lies, out of the personal and the political, a book nurtured by a threads of reading, the stepping stones, poetic pivots and ideas that infuse and influence the making of a poem.

This is also a book nourished by ‘enthusiastic poetry talk’, with dear friends and writing companionship. And that matters. It is heartwarming to read Emma’s notes and acknowledgments. To think of poetry as conversation in myriad directions. One poem is an almost fan letter to Janet Frame, another a subconscious dialogue with poet Poppy Haynes.

As the title suggests, Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit is a book of lies, from little to large, from under the threat of torture or a mother’s stern gaze, from a homeless man scamming sympathy with self-inflicted wounds to lies told to save face or skin.

Emma’s poetry has always been a gift for the ear, and this collection is no exception, the linguistic dexterity, the rich lexicon. With her new collection, there is a terrific density of sound and effect. Every poem an intricate arrival of sonic mesh knit chord soar whisper. How it strikes the heart as you read.

To be reading this book is so very timely, when we are grappling and despairing at inhumane leadership, at planet-and-people-polluting toxic lies, at the self-serving manipulations of self-serving politicians. How to read and write in the age of weasel Trump and weasel Luxon Seymour Peters? What can language do? Ah.

I hold this book close to my heart because it reminds of the reach and possibilities of poetry. We can speak of the child, sons and daughters, mothers and fathers. We can write of loss and love, grief and abuse, epiphany and recognition. Failings and flailings. We can write out of and because of omission, and we can write out of and because of erasure.

There are multiple tracks and clearings as you read. You might feel the sharp blade of reading along with the sweet balm of self care. Take ‘Genealogy’, for example, a poem that steps into a complicated weave of ancestry, where Emma asks, so astutely, ‘is every white genealogy poem an erasure poem / is every postcolonial poem an erasure poem will we ever be fair / and true and clear’.

Or take ‘An Abraham Darby Rose’. Take this poem and sit with under the tree in the shade and embrace its physicality, an attribute that is a gold thread of the collection as whole. Spend time with the rose, honing in on both thorn and petal (‘peach-toned ruffles’), before facing the needle sting of the son’s departure, the self-examination within the greater context of life – and sit there finding ripples of comfort as the speaker gently places plantings in ‘the soil’s quiet crib’. Take this poem and hold it close.

Imagine we are in a cafe. Imagine we are in cafe reminding ourselves that silence is a form of consent. To write is to fertilise our community gardens. To write, as Emma does, and speak of tough stuff is to strengthen who and how we are in the world. To navigate, as Emma does, being mother daughter sister friend. Human and humane being. To gather a box of groceries for the welfare centre: ‘in the hope that kindness migrates invisible currents / to pollinate every tyrant’s heart’ (from ‘Wanting to believe in the butterfly effect’). To gather a folder of poems.

Ah. This precious book with its layers and weave of vulnerability and admission. This book of hauntings. This haunting book. This necessary fertile sequence of plantings. I love this so very much indeed.

The Lake

This child feels it like blue pollen that makes her hive of fingers dance.

This one a groove along his spine that must be filled with running.

Another as music that only rises here, deep in his mind, never sung.

This last, as crystal numbers that link, fold and fall like pleats in time.

We think they all must know the lake’s mother tongue.

They are her water cupped in our hands,

new skins for the old light we believed in.

Photo credit: Caroline Davies

six questions

Were there any highlights, epiphanies, discoveries, challenges as you wrote this collection?

One of the challenges was in whittling down the original manuscript to give some titles more room to breathe. I had to discard about sixteen poems to streamline things. This meant taking out poems about Putin and Trump; about the Erebus disaster, with Justice Mahon’s infamous phrase ‘a litany of lies’; a playful poem about fake orgasm; darker poems about anorexia; domestic violence; gaslighting; and more besides. I had to think hard about which remaining poems would still carry traces of some of the social and political power dynamics I was preoccupied by.

Is there a particular poem in the collection you have soft spot for?

It’s less a soft spot than a sense of relief that I’ve managed to wrestle the difficult material into a poem with its own shape and forward drive. ‘My Blank Camouflage’ has been more than 30 years in the making, in that it’s taken me that long to find a way to address the topic in a poem.

What matters when you are writing a poem? Or to rephrase, what do you want your poetry to do?

I want to choose the words so that each potential nuance fuels and remains true to the poem’s psychological energy. I want the poem to resonate with sonic qualities so that it shows traces of its musical ancestry. I want the poem to have a hot nucleus of emotional truth.

I would find this impossible to narrow to one example, but is there a poem by a poet in Aotearoa that has stuck with you?

As I get older, answering this kind of question feels less and less possible! So many have stuck with me, that narrowing it to one feels like a falsification. And what sort of world would we be in if only one poet really spoke to us?

Are there particular poets that have sustained you, as you navigate poetry as both reader and writer?

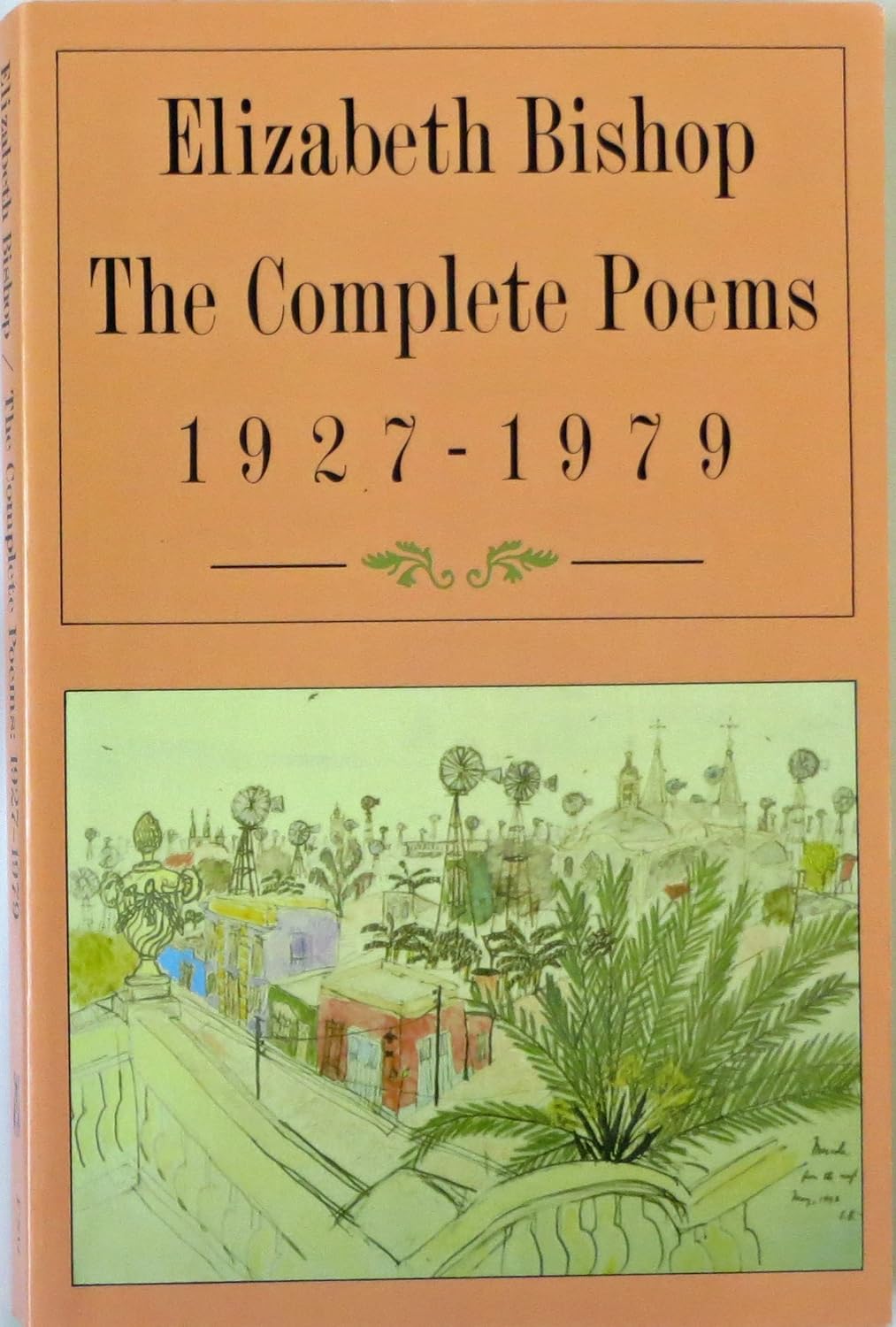

What sustains me is the very fact that there is such a wide range of poets out there, past and present, reminding me that poetry itself is such a capacious, expansive genre. I’ve really enjoyed reading my fellow short-listed poets over the past week: three very different poets, all with resonant voices. I’ll cheat here, and catalogue some of my other recent reading: I’ve lately returned to reread Elizabeth Bishop’s Collected Poems and was struck by poems that hadn’t lingered with me before, although she is someone whose work I’d read and taught over the years. This was a thrilling realisation: to see how age and time uncover fresh potential, fresh insights, in long-term loves.

I recently came across the work of Norman MacCaig, a Scottish poet who was totally new to me, although he lived from 14 November 1910 – 23 January 1996. It was again thrilling to realise that I could still experience that falling-upon-a-poet with the same delight, absorption and a sense of reading as energising that I had as a young hopeful writer. There is something magically transporting when his work is firmly grounded in the sparkling, sensuous natural world.

I also recently came across the work of young UK poet Ella Frears: her work is much grittier and more urban than a poet like MacCaig; it’s sassy, frank, darkly funny sometimes, and vinegarish with satire.

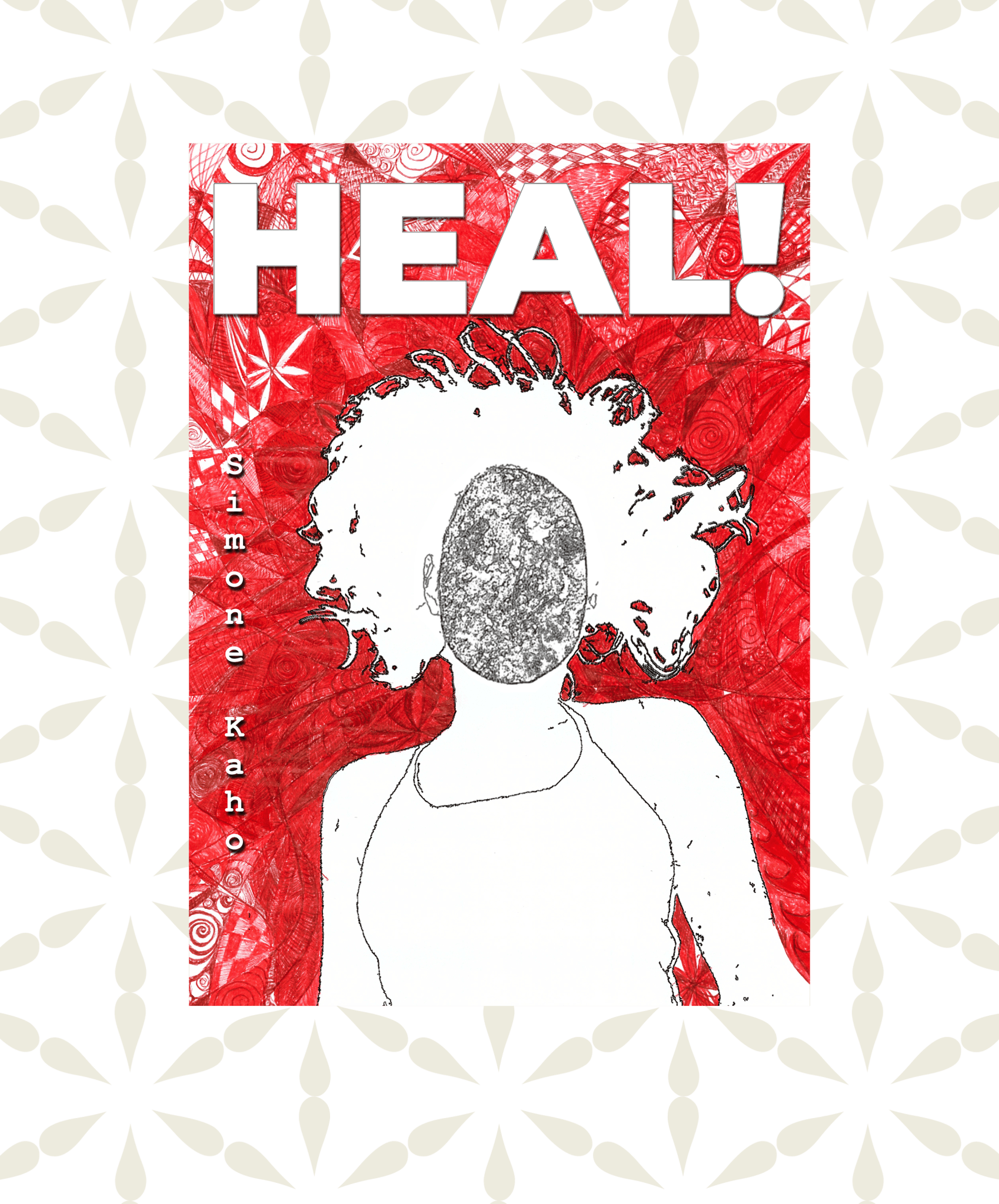

I’ve also recently re-read Heal! by Simone Kaho; the lyricism and honesty in this moved me all over again. As I said elsewhere, when it first appeared, it has a fiery lyricism, even when it’s a sister of narrative prose and it serves a productively discomforting exposure of all kinds of inequality. I loved it in a stirred-up way.

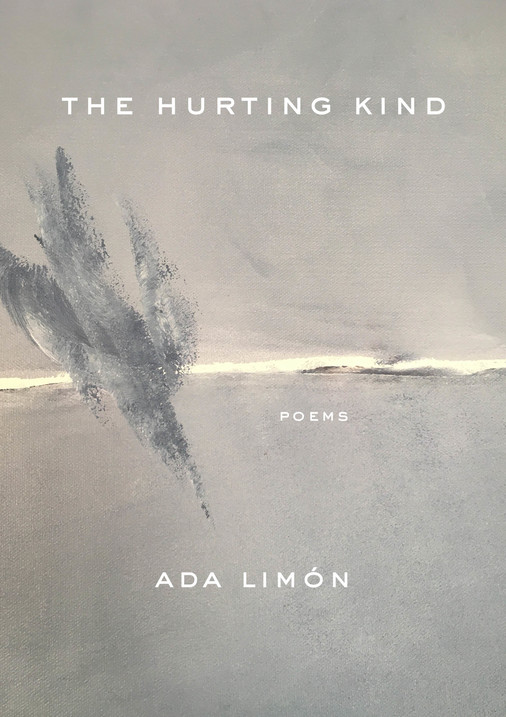

Every now and again, I’ve been dipping back into collections by Ada Limón and feel both recharged and calmed by her ability to compress disparate experiences, contraries, into compact, contained, controlled and intimate lyrics.

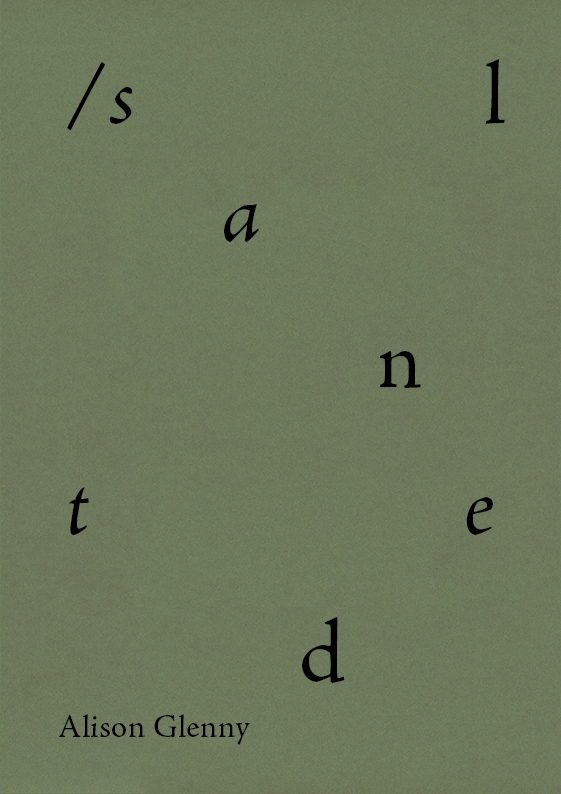

And I’m in awe of how Alison Glenny, in her new collection Slanted, turns the page into such a flexible and evocative visual and typographical field. It is like watching a combination of a visual artist carefully etching lines, and a skilled gymnast dance across and transform a tumbling floor.

We are living in hazardous and ruinous times. Can you name three things that give you joy and hope?

- The miracle of something as plain and ugly as a tuber containing the diva of a dahlia.

- Intelligent, compassionate, excellent communicators, such as, say, the poet and academic Claudia Rankine, or the neuroscientist, literary critic and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, whose work I’ve only just stumbled recently also, via podcasts: I haven’t read his major work, The Master and His Emissary, but now I feel a sense of happy urgency about tracking it down. (Not having read the book, I hasten to add that I can’t yet know if I agree with all his views: and the point of having an open, intellectual society should mean having the freedom to disagree, even with people we admire.) The fact that there are deep, empathetic thinkers out there, capable of linking disparate disciplines and social phenomena together, and conveying their ideas in multiple forms and media: this gives me hope that the best of humanity will persist against the narcissistic, cruel and hateful.

- My extended family, and in particular, my own children. One is an independent adult, now; one is still in high school. Despite all I fear for them, and all the things I worried were flaws and inadequacies in myself as a parent, they astonish me with the way they approach the world with entirely their own attitudes and with strengths that I never had. An analogy must be that if their father and I were the tubers, they are the dahlias. Their own extended family would be soil, rain and sun.

You can hear Emma read poems here

Emma Neale is the author of six novels, seven collections of poetry, and a collection of short stories. Her sixth novel, Billy Bird (2016) was short-listed for the Acorn Prize at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards and long-listed for the Dublin International Literary Award. Emma has a PhD in English Literature from University College, London and has received numerous literary fellowships, residencies and awards, including the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for a Distinguished Contribution to New Zealand Poetry 2020. Her novel Fosterling (Penguin Random House, 2011) is currently in script development with Sandy Lane Productions, under the title Skin. Her first collection of short stories, The Pink Jumpsuit (Quentin Wilson Publishing, 2021) was long-listed for the Acorn Prize at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards. Her short story, ‘Hitch’, was one of the top ten winners in the Fish International Short Story Prize 2023 and her poem ‘A David Austin Rose’ won the Burns Poetry Competition 2023-4. Her flash fiction ‘Drunks’ was shortlisted in the Cambridge Short Story Prize 2024. The mother of two children, Emma lives in Ōtepoti/Dunedin, Aotearoa/New Zealand, where she works as an editor. Her most recent book of poems is Liar, Liar, Lick, Spit (Otago University Press, 2024).

Otago University Press page

Pingback: Poetry Shelf on the Ockham NZ Book Awards | NZ Poetry Shelf