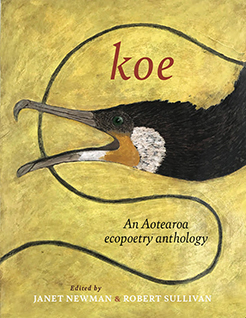

Koe: An Aotearoa ecopoetry anthology

edited by Janet Newman and Robert Sullivan

Otago University Press, 2024

Ecopoetry. I have been musing on the slipperiness of poetry labels and categories. Poetry has always re-presented and celebrated nature, drawn upon its beauty and its wild-er-ness, used it as a source of comfort, healing, symbolism, bridges into states of mind, a way of mapping the coordinates of home. But what shifts when ecosystems are under increasing and devastating threat? How do we write nature? Every morning I wake up to the radio and social media scrolling the evil choices of [some] world leaders and it forms a heavy overcoat of darkness. What we are doing to this planet is unforgivable, to nature, to people, to creativity, to the stories we tell, the justice we build, the lives we save. Heartbreaking.

So what good is poetry?

Janet Newman asks at the beginning of her unmissable introduction to Koe: An Aotearoa ecopoetry anthology: “Can poetry save the earth?”. A question that reverberates across the globe as poets struggle to write in a climate of catastrophe. Not just the environment. Not just nature. I keep returning to the notion that poetry is an incredible aid and homage to life. To write a nature poem might be to write beauty and wilderness but to write an ecopoem might be to widen that view. I live near Te Henga Bethells Beach, a place dune-ravaged in the Gabrielle cyclone and storm, where dottorel are under continued threat, where the wetlands are fragile and contested. I wrote a poem to go on the visitor booth at the start of the beach. Is it a nature poem? Is it an ecopoem? Who knows? The poem is an entry point into a place we locals hold in our hearts. A place we are working hard to protect. I have carried the beach image though the wounding shards and cracks of the past three years, through the pandemic, as balm for my stuttering health coupled with our stuttering planet.

So what good is poetry?

Koe: An Aotearoa ecopoetry anthology was a timely arrival late 2024. It is an anthology lovingly edited and introduced by Janet Newman and Robert Sullivan and, with equal love and care, designed and produced by Otago University Press. Janet and Robert place ecopoetry within the context of Aotearoa, where the first voices are the tangata whenua. Where Māori poets were singing the land’s beauty and bounty and narratives as a taonga not to be taken for granted. As a taonga to be conserved and nourished.

‘Koe’ is a bird cry and also a scream, as Robert suggests via H. W. Williams’s Dictionary of the Māori Language. Robert writes: ‘a disturbing scream from the forest, or the shore, or the marshes, or the bushlined gullies and gorges, or its absence from the paddocks, the eroded dead-timber hillsides and mountains, the oxidation of ponds and outfalls.’

Poetry as scream.

The anthology is divided into three parts: ‘The early years’, ‘The middle years’, ‘Twenty-first-century ecopoetry’. I love this. I love being transported across the different attachments to nature, to the environment, to ways of singing contemplating challenging screaming. And yes this Aotearoa, this ground we stand on, in which we plant multiple roots, this ground is colonised contested stolen. Janet and Robert have gathered an anthology of voices across time culture location preoccupations experience to unsettle and resettle the view. The views. It is personal and political.

Poetry connecting me to you to planet to you to me.

Poetry as challenge.

Poetry as beauty and kindness.

Poetry as hope.

To celebrate the anthology, five poets read a poem and Janet answers five questions.

The readings

Ash Davida Jane

photo credit: Ebony Lamb

‘2050’

David Eggleton

‘A Report on the Ocean’

Rebecca Hawkes

‘The Land Without Teeth’

Erik Kennedy

‘Phosphate from Western Sahara’

Kiri Piahana-Wong

‘Piha’

5 Questions for Janet Newman

Editing a poetry anthology can offer multiple joys as you scavenge your shelves, libraries and the archives for poems. What surprised or delighted or challenged you?

I was surprised that Aotearoa New Zealand did not have an ecopoetry anthology. Much of this country’s poetry and indeed literature is focused on the landscape and relationships between people, land and sea, so it seemed we should have been one of the first countries to explore our ecopoetical heritages. Once I started delving into New Zealand’s ecopoetry I was surprised to discover that even in colonial times when European settlers were felling the forests, their poets were portraying senses of loss. Not only loss of the forests but of the solace they provided, and also loss of the living things forests supported: vines, ferns and bird life, so an awareness of ecological interconnection. Once I started looking outside of the English poetry canon it was no surprise to find that traditional Māori poetry showed emotional, cultural and physiological attachment between people and nature. What was surprising, however, was the total absence of poetry stemming from the Māori tradition in the English poetry canon until as recently as the second half of the twentieth century. It also struck me that the concept of culture as a part of nature and vis versa, portrayed at first in English in poems by Hone Tuwhare, were entirely alien to an English speaking audience and treated as something other by critics at the time. It shows how much has changed in this country if we look, for example, at the granting this century of legal personhood to the Whanganui River, Te Urewera and Mount Taranaki.

The biggest surprise of all, though, was how critics primarly in northern hemisphere countries appeared to be completely unaware of such concepts in which human and nonhuman worlds are entwined and defined ecopoetry in terms of duality between nature and culture. It was satisfying to discover that this country’s ecopoetry is not only a unique, local variant but that it expands current Eurocentric characterisations of the field. I feel proud to belong to a country with rich poetic heritages that recognise and value the importance of different relationships between people and nature. Nevertheless, Aotearoa New Zealand’s ecopoetry is saturated with loss. Loss of ecologies and loss of a sense of belonging. So it was heart-rending to read Romantic ecopoems revelling in solace in a nature constructed by colonisation which were written at the same time as marginalised ecopoets portrayed a sense of alienation through the loss of land and indigenous species.

I love how the anthology is divided into three sections: ‘The Early Years’, ‘The Middle Years’ and ‘Now’. What struck you about how poetic attachments to the land, shores, forests, skies have travelled over time? What connections and disconnections, challenges and homages?

Over time, the Māori and English poetry traditions which are the heritages of contemporary Aotearoa New Zealand ecopoetry are drawing closer together. In earlier years, there was wide separation. The nineteenth-century genesis of New Zealand ecopoetry in English is marked by fatalism towards a dying nature, such as William Pember Reeves’ “The Passing of the Forest” (1898). Conversely, just nine years earlier, Pāora Te Pōtangaroa reissued Te Kooti Te Arikirangi Te Tūruki’s moteatea, “Kaore Hoki Taku Manukanuka,” which called on nature, specifically the behaviour of the mātuhi (bush wren), as a model for iwi to unite against British takeover of Māori land, hailing nature’s endurance during times of struggle. In the twentieth century, Pākeha poets wrestled with a sense of belonging in an alien land and found solace in the nature constructed by colonisation while poets from the Māori tradition mourned the loss of indigenous ecologies and Indigenous culture. This century, we see a coming together of the two traditions. Airini Beautrais’s “Trout / Oncorhynchus mykiss / Salmo trutta” recognises the detrimental effect of introduced trout on indigenous fish species. Dinah Hawken’s “Losing Everything” states ‘I am the beneficiary of injustice’ as it acknowledges that the poet’s forbears bought land illegally confiscated from Taranaki Māori. Te Kahu Rolleston’s “The Rena” relates the sinking of the container ship off the coast of Tauranga in terms of capitalist pollution of not only the sea––‘the realm of Tangaroa’––but also of kaitiakitanga and tikanga. Hinemoana Baker’s “Huia, 1950s” wrestles with the knowledge that the call of the extinct huia is preserved in a sound recording of a huia trapper mimicking the song. ‘I want to tug / something out of him’ she writes. These poems show the complexities of nature and the human relationship with it in a settler colonial country.

Is there a poem or two that particularly resonate with you?

A poem from The Early Years section that particularly resonates with me is Alan Mulgan’s “Dead Timber.” By finding that the only creative act of settler society is nature’s destruction, it connects ecological ruin with the shaping of a national character devoid of artistic or literary culture. The national character Mulgan is referring to is that of European settlers such as my forebears. Another poem that resonates shows a way of perceiving the natural world beyond my personal experience. Co-editor Robert Sullivan’s “Waka 16 Kua wheturangitia koe” in Star Waka (1999), in the list of Further Reading, mourns the diminishment of star light due to the artificial nightlights of modernity. By portraying stars as natural elements and guiding lights of ancestors, their diminishment is both a physical encroachment and a spiritual and communal violation.

In these earth-smashing times, I find myself drawn to writing the Te Henga beach beauty as much as writing poetry as both challenge and marker of human and earth catastrophe. How does this tension between beauty/solace and ruination/despair affect you as a poet?

Reading ecopoems has given me an understanding of the many different ways in which nature and the human relationship with it is conceived. As a farmer, I am working in a constructed nature and yet it contains animals and much beauty which together lend me a sense of wellbeing. However, farmland is a source of great loss and grief to tangata whenua, as Jacq Carter reminds in “Our Tūpuna Remain.” I am aware that the ecologies of the local places where I love to swim and enjoy ‘nature’–– Mānawatu River, Ōhau River and Waitārere Beach––are largely constructed by colonialism. “Nothing that meets the eye on a New Zealand coastal plain that has been the subject of a swamp drainage scheme is yet a century old,” writes Geofff Park in Theatre Country, Essays on landscape and whenua (2006). My poem “Koputaroa, near the Manawatū River” in Unseasoned Campaigner (2021) explores how “the recognisable combination of trees, pasture and human structures makes it seem perhaps as if they are all that was ever here.” Like you, Paula, I am caught between appreciating beauty and acknowledging loss.

It is on my mind every day. How to navigate this toxic world? What gives you joy? Hope?

It is in poetry that I find joy and hope. As Gail Ingram writes, poetry “moves us … by bearing witness to pain, joy, all that our community is … it gets us back to living again.” Finding in poetry the expression of feelings of fear and optimism similar to my own gives me a sense of community:

song coming.

Song coming, beyond any

we’ve ever before lifted in song.

Carolyn McCurdie, from ‘Ends’

The readers

Ash Davida Jane is a poet, editor and reviewer from Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Their second book How to Live With Mammals (Te Herenga Waka University Press) won second prize in the 2021 Laurel Prize. They are a publisher at Tender Press and reviews co-editor at takahē.

David Eggleton lives in Ōtepoti Dunedin and was the Aotearoa New Zealand Poet Laureate between August 2019 and August 2022. He is a former Editor of Landfall and Landfall Review Online as well as the Phantom Billstickers Cafe Reader. His The Wilder Years: Selected Poems, was published by Otago University Press in 2021 and his most recent collection Respirator: A Laureate Collection 2019 -2022 was published by Otago University Press in March 2023. He is a co-editor of Katūīvei: Contemporary Pasifika Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand, published by Massey University Press in 2024.

Erik Kennedy is the author of the poetry collections Sick Power Trip (2025), Another Beautiful Day Indoors (2022), and There’s No Place Like the Internet in Springtime(2018), all with Te Herenga Waka University Press, and he co-edited No Other Place to Stand, a book of climate change poetry from Aotearoa and the Pacific (Auckland University Press, 2022). He lives in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Kiri Piahana-Wong is a poet, editor and the publisher at Anahera Press. She is the author of two poetry collections, Night Swimming (2013) and Tidelines (2024), and the co-editor of Te Awa o Kupu (Penguin NZ), an anthology of contemporary Māori literature, as well as Short! Poto! The big book of small stories (forthcoming from MUP in June 2025). She lives in Whanganui.

Rebecca Hawkes is a queer painter-poet from a farm near Methven. Her first book is MEAT LOVERS (Auckland University Press). She shepherds the warm-blooded journal Sweet Mammalian and co-edited the anthology No Other Place to Stand. Rebecca is currently topsy-turvy between hemispheres studying an MFA in yearning (and, to a lesser extent, poetry) at the University of Michigan.

The editors

Janet Newman lives at Koputaroa in Horowhenua. She has a PhD from Massey University for her thesis ‘Imagining Ecologies: traditions of ecopoetry in Aotearoa New Zealand’ (2019). Her essays about the sonnets of Michele Leggott and the Romantic ecopoetry of Dinah Hawken won the Journal of New Zealand Literature Prize for New Zealand Literary Studies in 2014 and 2016. She won the 2015 New Zealand Poetry Society International Competition, the 2017 Kathleen Grattan Prize for a Sequence of Poems and was a runner-up in the 2019 Kathleen Grattan Awards. Her first collection of poems, Unseasoned Campaigner (OUP, 2021), won the 2022 New Zealand Society of Authors Heritage Book Award for Poetry.

Robert Sullivan (Ngāpuhi, Kāi Tahu) is the author of 10 books of poetry, a graphic novel and an award-winning book of Māori legends for children. His most recent poetry collections include Tūnui | Comet (AUP, 2022) and Hopurangi—Songcatcher: Poems from the Maramataka (AUP, 2024). Robert is the co-editor of anthologies of Polynesian poetry in English, Whetu Moana (AUP, 2002) and Mauri Ola (AUP, 2010), alongside Albert Wendt and Reina Whaitiri. He’s also the co-editor of an anthology of Māori poetry, Puna Wai Kōrero (AUP, 2014), with Reina Whaitiri. Among many awards, he received the 2022 Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for a distinguished contribution to New Zealand poetry. He is associate professor of creative writing at Massey University and has taught previously at Manukau Institute of Technology and the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Otago University Press page

Pingback: Poetry Shelf 2025 highlights (or some summer reading and listening) | NZ Poetry Shelf