Deserts, for Instance

The loveliest places of all

are those that look as if

there’s nothing there

to those still learning to look

Brian Turner, from Just This, VUP, 2009

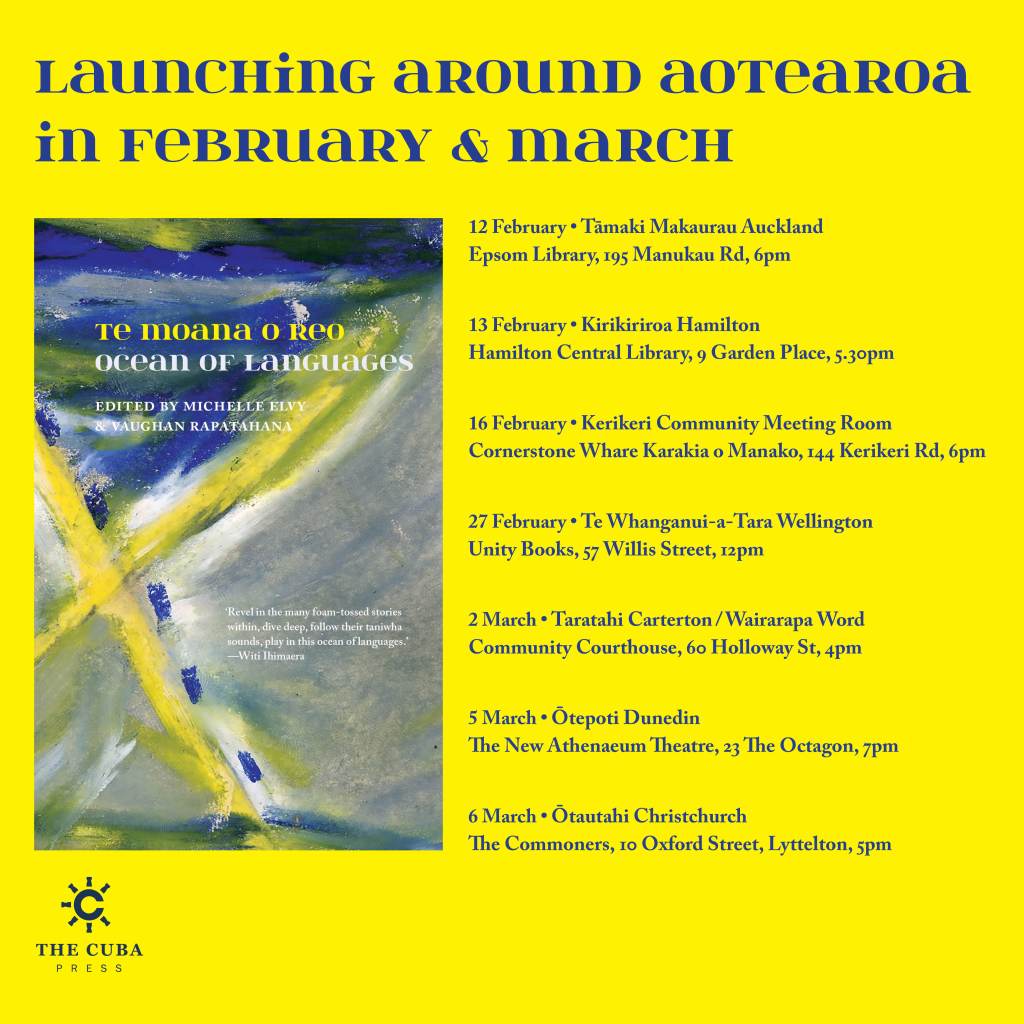

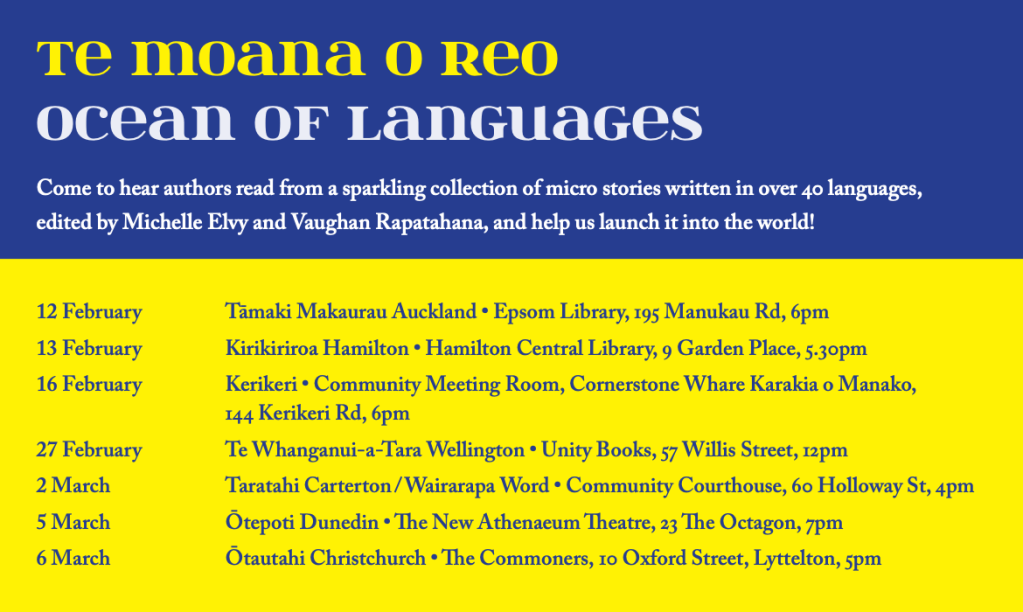

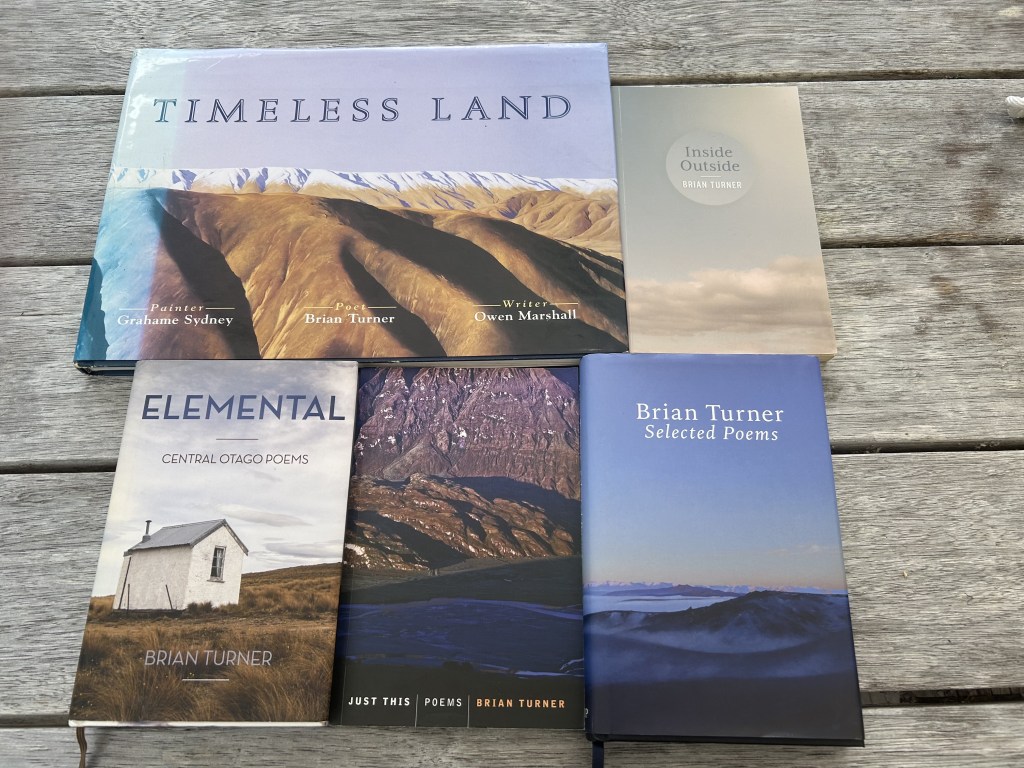

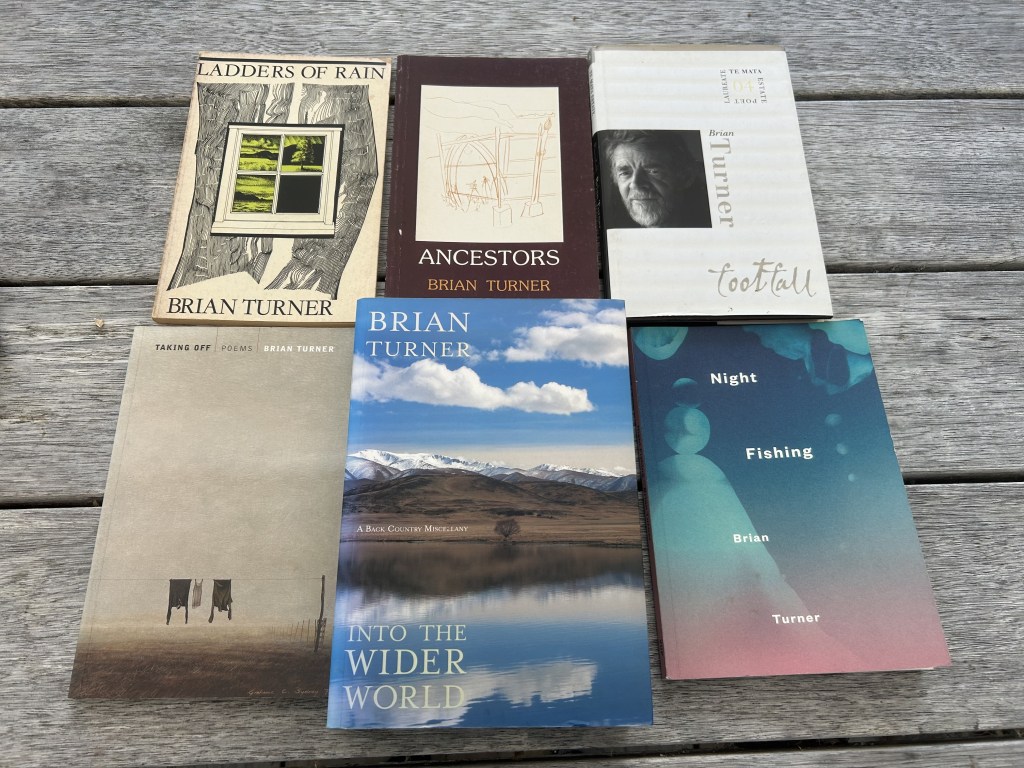

To read your way through Brian Turner’s poetry collections is to travel with open skies, shifting seasons, wide space, musical wind, rivers, stars, the precious land, a steadfast light. More than anything, to read your way through Brian’s poetry, from his debut collection Ladders of Light (John McIndoe, 1978) to his Selected Poems (VUP, 2019) is to savour the present participle, to be musing, absorbing, travelling, grounding, observing. With all senses on alert. With truth and fiction, fathers and sons, beauty and love, earth fire water air. With physical anchors and philosophical currents. With so many poems dedicated to friends, this is poetry as tender embrace.

If there is a vital core from which each poem lifts, it is an echoing question, what matters? And what matters is the way each poem is a conversation with, a link to, a rendition of home. Overtly, or less so. Home is where you stand, where you have stood, lay down roots, where you dream and love and die. It is experience and reality and dream. Questions. Connections. Epiphanies. In his introduction to Elemental: Central Otago Poems (Godwit, 2012), Brian underlines the primacy of belonging, the way the poet is both archaeologist and explorer. The way heart is woven from the blood and sinew of home, and home is formed from the blood and pulse of heart.

Poets — certainly poets like me — end up finding and revealing the self in where they come from, and hope to be able to say, eventually, this is where I most belong. All writers, not just poets, are explorers, archaeologists too; we grub, we dig, are often surprised by what we find. There is music, there is song, there is grace and, now and again, a place where peace of mind is at home; then one can feel confident and, for magical moments, comfortable and at ease. There, truly, is a wonderful place to be.

On such occasions I sense there’s something of the numinous, something sacred, in and about our surroundings. I mean this in a broad-brush spiritual sense. It’s as if the hills watch us, and ask if we are watching ourselves in them.

Brian Turner

from ‘Foreword’, Elemental: Central Otago Poems, Godwit, 2012

And herein lies the joy of reading your way through Brian’s poetry. As readers we too are archaeologists and explorers, because reading like writing can get you digging and delving and yes, dancing into and within the myriad dimensions of home. In this fragile world, with its blinkered planet-smashing leaderships7, how restoring it is to hold poetry close that navigates what matters. To hold home, however we define it, close, to write it, it sing it, read it to heart.

This poetry, together we toast and remember this beloved poet.

Fact of Life

Home is not where the heart is

it’s what the heart goes hunting for.

Brian Turner, from Night Fishing, VUP, 2016

Brian Turner was born in Dunedin in 1944 and lived most of his life in Central Otago. His first book of poems, Ladders of Rain (1978), won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize and was followed by a number of highly praised poetry collections and award-winning writing in a wide range of genres including journalism, biography, memoir and sports writing. Later poetry collections included Night Fishing (2016), Inside Outside (2011), Just This (winner NZ Post New Zealand Book Award for Poetry 2010) and Taking Off (2001). His Selected Poems were published in 2019. He was the Te Mata Estate New Zealand Poet Laureate 2003–05 and received the Prime Minister’s Award for Poetry in 2009. Brian died in February 2025.

Poetry Shelf invited twelve friends to choose a favourite poem by Brian and write a few words to go with their choice. I offer this tribute so you too may go travelling with Brian’s poetry, and may draw close to home and to heart.

A Tribute for Brian

Philip Temple

Ancestors

(for Philip Temple)

I came this way to shed some care.

Every stone I stumbled on, every

root that snagged my foot was

bastard discontent. By the time

I’d reached the hut I was too tired

to complain anymore. Shucking my pack

I lay in the grass that shimmered

in the breeze. The blue sky

preened itself. Wheels of sunlight

bowled along the valley. I dozed off

until evening crept over forest

and mountain. I knew they would

find me sometime. My speechless ancestors

played like mice among my dreams.

It grew cold. And colder. I woke

to the river running over my bed

of stone. I have come to know

that where a river sings a river

always sang. I listen.

This much I have learned.

Brian Turner, from Ancestors, John McIndoe, 1981

This poem was the eponymous title to Brian’s second collection in 1981. It preserves forever a moment we shared, a year earlier, ‘until evening crept over forest and mountain’ and we woke to the ‘bed of stone’ beside the Top Forks Hut in the Wilkin Valley. It had been a long tramp on a hot day and we were both buggered by the time we got there, thankful to be able to drop our heavy packs and collapse on the grass. It was the beginning of our last real climb together. The next day we made the first ascent of a peak that was un-named despite its height and lowering presence 5000 feet above the joining branches of the river.

But the poem was more than commemorative or even marking, in its dedication, the unbreakable bonds of our friendship. It spoke for both of us of the wordless ancestors running in the rivers and embedded in the mountains. There is a universal understanding of this that is expressed in different ways in particular cultures but which transcends them all. Brian’s great contribution in his poetry and other writing was to express this so conclusively for everyone. His work will continue to give us the assurance we belong.

Philip Temple

Bridget Auchmuty

Hannah’s Kitchen, Hayes Cafe in Oturehua

The River in You

(after W.S. Merwin)

The first thing you want to hear

is the river sound

and then to see

the source of that sound

for it’s never the same

yet it’s always something like

what you think you remember

from the time before

and the one before that

and when you reach the bank

though you no longer hurry

as you used to and look down

on the long reach that flows south

and curves east like a wing

light and sound are one

and you know the swirl

of having been there before

though it’s not quite the same

as last time and the time

before that and you sense the pull

that draws you back is the river in you

racing to keep time with the river sound

Brian Turner, from Taking Off, Victoria University Press, 2001

One of the things I loved about Brian was his generosity: with his encouragement of other writers, with his tireless voice for wild places, with his time in helping out in practicalities. When I stopped being in awe of him and he became a neighbour and friend, we had numerous evenings in the village reading each other’s work over dinners at a variety of houses, countless coffees at the local café, where the staff always brought him the largest possible cheese scone or muffin, and conversations that ranged in breadth and depth but were never dull. In his poetry he was of course a master of nailing time and place, but the best of his work was so much more than just that, turning from the immediate to a universal comment on what it is to be alive. I miss seeing him as a yellow blur on his bike or trundling firewood in a wheelbarrow home from the domain, but mostly I miss his immense presence on the lit scene of Aotearoa.

Bridget Auchmuty

Owen Marshall

Brian Turner, Owen Marshall (standing), Grahame Sydney, Cromwell

Snow in September

Someone I’ve yet to meet

is playing a violin in the snow

in a field nearby

and it sounds like Beethoven

to me, and under the willows

by the stream

a young boy is weeping.

When the music stops

the boy will disappear

as he does every time,

every time.

Brian Turner, from Night Fishing, Victoria University Press, 2016

Brian and I were friends for 44 years, visiting each others homes and families, on book tours or at festivals together, walking in the hills, but my best memories are of our collaboration with mutual friend artist Grahame Sydney, on the illustrated books Timeless Land, Grahame Sydney, Brian Turner, Owen Marshall (Longacre Press, 1995) and Landmarks, Grahame Sydney, Brian Turner, Owen Marshall (Penguin, 2020), which celebrated Central Otago – Brian’s homeland. We three were on the same page, in both senses of the phrase. Brian felt deeply and thought deeply, although often disguising both behind a gruff exterior. In poetry he expressed himself without reserve and with impressive power and sincerity. I miss him, but the poems live on.

Owen Marshall

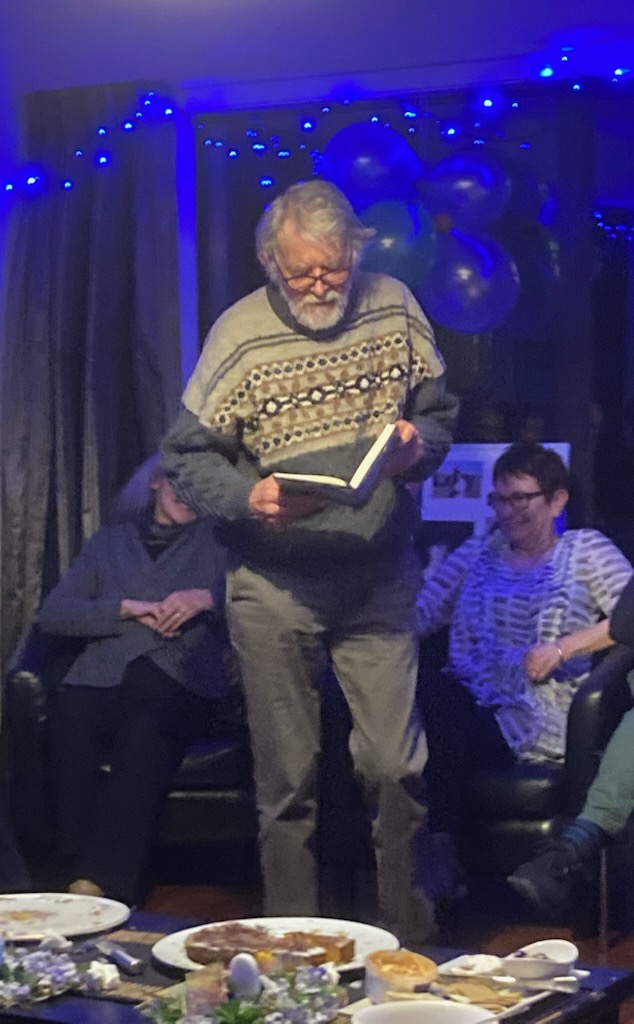

Peter Ireland

Photo credit: Mark Beatty, The Circle of Laureates Reading

National Library, 11th March 2016

Place

Once in a while

you may come across a place

where everything

seems as close to perfection

as you will ever need.

And striving to be faultless

the air on its knees

holds the trees apart,

yet nothing is categorically

thus, or that, and before the dusk

mellows and fails

the light is like honey

on the stems of tussock grass,

and the shadows

are mauve birthmarks

spreading

from the hills.

Brian Turner, from All That Blue Can Be, John McIndoe, 1989

The poetry of Brian Turner is a paean to the local; poetry grounded in a particular setting, but redolent of universal meaning. As an epigram for his poem Just this, Turner quotes the American poet and environmental activist Gary Snyder:

Find your place on the planet, dig in,

and take responsibility from there.

The ‘place’ for much of Turner’s poetry is the landscape of Central Otago, which is where he lived from 1999. The tiny settlement of Oturehua, in the Ida valley of the Maniototo river, was where Brian Turner dug in. An English translation of Oturehua is ‘the place where the summer star stands still’, a perfect setting for a poet whose lifelong quest involved trying to ‘find and hold on to anything that’s struck me as heartfelt and constant, something that seems durable and likely enduring.’ In poems of plain-speaking eloquence, which ‘crackled with the intensity of their sheer power of observation’ Brian Turner reminded us to pay careful attention to nature, to protect it from the depredations of the heedless and to be enchanted by the rhythms of rivers and hills.

The National Library acknowledges with sadness the passing of Brian Turner, a much-loved figure in New Zealand Literature and in the promotion of environmental awareness. Brian was Te Mata Estate Winery Poet Laureate between 2003 and 2005. In November last year he was made New Zealand Poet Laureate of Nature for his lifetime’s work in poetry and activism, fighting for and celebrating the natural world.

Peter Ireland

Kay McKenzie-Cooke

Blackbird

When a blackbird starts singing

high in the silver birch

and dark‘s hovering

heartfelt beats heartless

hands down. And it seems

to those who hope to

discern the difference

between love and loveliness

that the bird’s song may be as pure

as any we’ll ever hear, and is part

longing, part fulfilment, near

unadulterated joy. And though

one can’t say that a bird

wonders if remorse will ever

run its course,

that blackbird sings in ways

that assuage need in a voice

that’s his alone until, miraculously,

it feels as if I’m singing too,

him to me and me to him. And

both of us for all of us.

Brian Turner, from Night Fishing, Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2016

This is Brian Turner writing in a modern, unashamedly Romantic poet’s vein, unapologetically describing nature’s ability to transport us to another realm. The craft in order to attain the sublime is particularly satisfying as I remember attending a workshop of his back in the late ’80’s (when he still had red hair) where he spoke of how really hard a poet must work to compose poetry that appears effortless. I love the lines:

‘and dark‘s hovering

heartfelt beats heartless

hands down …’

Magic. Pure Turner. Pretty sure I heard him read this poem at a reading and I can still hear his gravelly voice. I hope I can keep hearing it through his poetry for a long time yet. Encased in the last lines is Brian’s absorption into the pure, unifying aspect of nature and its reach into his innermost being. The lines reflect how circular, open-ended, inclusive and all-encompassing nature can be if we allow it to enthral us, as Brian Turner surely did, ’For all of us’.

Kay McKenzie-Cooke

Grahame Sydney

Grahame and Brian, 2014

After

for Grahame

The dead do

sing in us, in

us and through,

us, and to themselves

under their mounds of earth

swelling in the sun, or in their

ashes that shine

as they depart on the wind.

See how the grass

sways to the sound

of their voices

under, singing

the beautiful

eternal sadness

of before

relieved of the

resolve of after.

Brian Turner from All That Blue Can Be, John McIndoe, 1989

In late 1986 my father died. A mis-diagnosed prostate cancer had invaded his bones and his decline was remorseless, painful and heartbreaking, a full year of undeserved distress borne with courage. He was a man I admired immensely. Whenever anyone remarks on how like my father I am, I take it as the greatest possible compliment.

Brian and I spent hours every week on our road bikes, training together for races and events on the roads around Dunedin and he was following closely my dear Dad’s decline, fully aware of how it was impacting on me.

My family were at the hospital bedside the night Dad breathed his last long gasp, and I left a message on Brian’s phone to tell him. When I made it home a few hours later the sun was rising and I automatically, unthinkingly checked the mailbox as I walked past. There was was an envelope with my name , and inside an A4 sheet with this poem. “After” inscribed in Brian’s cramped, cursive hand.

A small gift from a mate. It appeared in the collection All That Blue Can Be in 1989.

Grahame Sydney

Richard Reeve

Ida Valley, January

This is the time

when the windows

rattle in the nor’wester,

scotch thistles prepare to seed

and the lucerne’s waving acres

of violet and green. Young thrushes

and blackbirds risk their lives

on the ground. My neighbour’s cat,

gingery, austere, is meant

to protect the raspberries

from the avians and doesn’t.

I go to bed only half-pie

sound in mind and body

and the mind starts roving,

wars with sleep, always

finds something else

to take issue with.

Brian Turner, from The Six Pack, Whitireia Publishing, 2006

What I like about this poem is its shape, and the counterpoint of that defined word-sculpture with the loose commentary that forms the poem’s content. What does the shape represent – a cloud, schist, wind-bent branches, the waving crop? All of these and none of them. No express link is made, yet we are invited to consider the text as an artefact of the composite phenomena that have given rise to the poet’s unease. Whereas the commentary captures dramas in the lives of various mortals affected by the gale – grounded thrushes and blackbirds risking their lives, the neighbour’s cat in dereliction of his duty to protect the raspberries, the poet unable to sleep – the indented left edge of the poem asks us to frame those dramas in a wider context, that of an elemental universe inextricably bound up with our day-to-day affairs.

Richard Reeve

Dougal Rillstone

October on the Otamita

to Dougal, who knows it best

Walking upstream it’s as if the water’s

flowing through me, jigging my heart

and telling me

this is the best I’ll be.

The wind breathes on the river, lightly

and the hot October sun

bastes a glaze on the water

that shines like shellac.

Great shaggy tussocks

bend and nod in the breeze.

Some have shambled to the stream’s edge

where they dip their heads to drink.

The white wild flowers are love letters,

unaddressed, and cast upon the hillsides.

Beneath the earth

is where the uncomplaining people lie

irrespective of what was said and done.

So there’s no justice, they say,

and furtively pluck each other’s sleeves

while the water tap dances and sings

Look at him, look at him,

wasting his heart here

and he doesn’t seem to care.

The shadows of fleet clouds

cover me like wings

and pass on.

Brian Turner, from Bones, John McIndoe, 1985

I said goodbye to Brian towards the end of January, not realising it would be for the last time. Dementia had erased most of his memories, and on that visit he struggled to remember me. And then, over coffee, he cocked his head to one side, fixed me in his stare, and said, “You and I, we’ve cared about rivers for a long time.” I looked back through teary eyes and said, “We have, Brian.” Later, I recalled the first time we met, back in the 70’s, when we also talked of rivers: about how much they meant to us, and the fears we held for their right to run free and clean. Rivers and the trout that inhabit them ran through our friendship for almost fifty years.

I chose ‘October on the Otamita’ because it explores the connection moving water has for those caught in its thrall. The original copy of the poem Brian handed to me four decades ago is one of my most valued possessions.

Dougal Rillstone

David Eggleton

Weekends

They hammer they saw they mow

they dig and weed they wed

someone or other for better

rather than worse though it doesn’t

always work out that way

when heartlands are heartless

But for now they mow

it’s the song of the weekend

the world’s at their feet

for this is a civilized place

and we believe in grass

A sun-glassed babe pilots a ride-on

and across the road

a mother of two

pushes something less superior

back and forth

on the roadside verge

When the mowers stop

you can hear trilling again

melodies in the shrubs and trees

and tulips like goblets full of sunlight

shine in gardens entrusted to us

Who knows impermanence

may not be permanent after all

if you find time to take stock

think of what a place could be

when it’s not what we possess

that counts most

but what we are possessed by

Brian Turner, Landfall 231

I’ve chosen a poem that I have selected from a sheaf Brian Turner sent me when I was editor of Landfall, and it was first published in Landfall 231 in 2016. This poem ‘Weekends’ is hard, bright and clear – joyous and yet intrinsically comical as it celebrates the industry of the Kiwi weekend. Other poems in the sheaf, name-drop variously Wallace Stevens, Fernando Pessoa and A.R. Ammons. As poems, they tend to feel a bit too diffuse, part of Brian’s personal philosophical project, ruminating about how to live a good life or make existence meaningful – and if it’s possible to actually achieve that. I read with Brian at events multiple times, and I remember him telling me on one occasion a while back that I looked as if I was dancing, skipping about while I read. He added, quoting from a poem by the Australian poet Les Murray: ‘I don’t do that. I’m like Les Murray: “I only dance on bits of paper.”‘ But what a lyrical dancer he was as a poet, with a lyricism grounded in the body, as when he writes of throwing himself on the mercy of the morning and floating like thistledown across the landscape on his bicycle, or catches skeins of wind with his ear: ‘I saw tussock, heard it/ speaking in tongues/ and chanting with the westerly’. He was someone girded about with laconic utterances and sawn-off proverbial sayings that might be waved like farmers’ shotguns to ward off trespassers. He was a poet of place, a poet of Otago, channelling topography as morality, while ever alert and open to the grace-notes of landscape : the fog that sits ‘on the river/ like a marquee’; butterflies that are ‘bright cloth/ caught in webs of sunshine’.

David Eggleton

Alexandra Balm

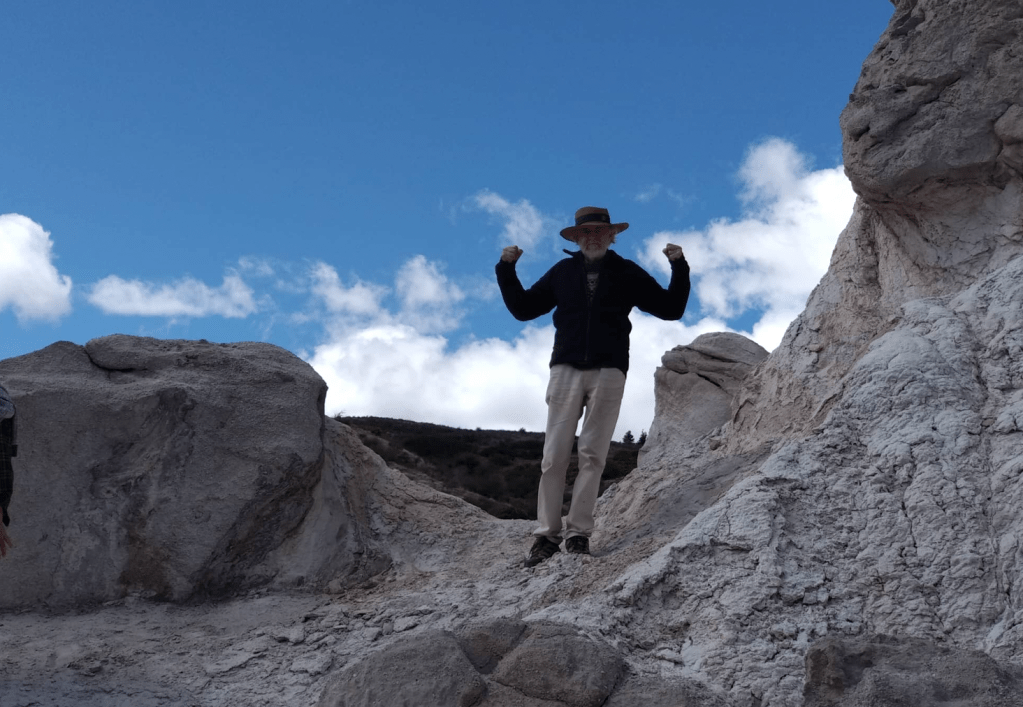

Brian holding up the skies, September 2022, Blue Lake, Central Otago

Sky

If the sky knew half

of what we’re doing

down here

It would be stricken,

inconsolable,

and we would have

nothing but rain

Brian Turner, Just This, VUP, 2009

Six years into my Kiwi adventure, I learnt of Brian Turner from Jillian Sullivan, then a friend of a friend. Kiwi American writer Garry Forrester had introduced Jillian via emails as a “fine writer.” I was completing a PhD on metamodern literature and was on the lookout for writers who expressed the metamodern paradigm of authenticity, interconnections, self-transformation, and care (for others, for the environment, etc). Jillian was in the process of building her strawbale house in Oturehua while editing her poetry collection parallel. During the ensuing email conversation, she mentioned a kindly neighbour, Brian Turner, himself a writer, who’d turn up with snacks of sliced oranges for the builders.

I started reading Brian’s work, first the fishing, mountaineering and ecological prose vignettes about Central Otago, then the poems. We exchanged a few messages, each of them an encouragement, an empathetic nod, or a nugget of wisdom: “We as humans talk about others, and other creatures; we talk to ourselves and to others; we seek enlightenment and various forms of fulfilment. We are a phenomenal species that wrestles with rights and wrongs… we find it easier to talk than to listen carefully to what others say and think.”

I tried to listen. My favourite is the poem ‘The Sky’ (Just This, 2009), which I had listened to online prior to meeting BT for the first time in Dunedin 2014, at Jillian’s book launch. I read it again in Glenn and Sukhi Turner’s home on the shore of Lake Wanaka. It was Valentine’s Day 2015. Instead of having a quiet day by themselves, Brian and Jillian had decided to share a few hours with people who loved poetry. A most generous gift to a ready audience.

After the reading, Jillian, who’d become a close friend, extended an invitation from Brian to have a cuppa at his brother’s house. In the hallway, behind a pan of framed glass, Brian’s poem presided over the quiet summer afternoon. It stayed with me after years. The poem speaks of the tension between superior levels of existence and the mundane, between what we should be doing and what we actually do. It gestures towards a living, breathing universe of which we are part and for which we should care. But which we disregard and insult every day. It also speaks of the poet’s ability to capture truth beyond the obvious and to express the interconnectivity of all things.

Alexandra Balm

Michael Harlow

Jillian Sullivan, Michael Harlow, Brian Turner

Dream

If you were here beside me now, the fire

cackling like my grandmother used to,

the sky soaked in stars, there’s

a whole bucket of words and phrases

I would sing: garden, bloom, memories,

river, sky, tenderness, valley, tulip,

japonica, rose, your fair skin, breath,

happy smile, Stingo, varoom, sweetie darling,

a love of art and style and a hunger

for a fairy tale world without end.

Brian Turner, from Inside Out, Victoria University Press, 2011

A love poem so characteristic of Brian, combining all those animated images. All of which are framed by Nature. Like so many of Brian’s poems love and nature are One. Brian’s language is so alive since feeling is first. How well I remember those occasions when Brian, Jillian, and myself were together either at the Muddy Creek Café or out-of-doors. Brian inevitably gave his attention to the things of the world. He once said to me as we were sitting outside his house in Oturehua gazing at the landscape: When I talk to the mountain the mountain talks back. Brian and Nature One. The Poet Laureate of Nature.

Michael Harlow

Sue Wootton

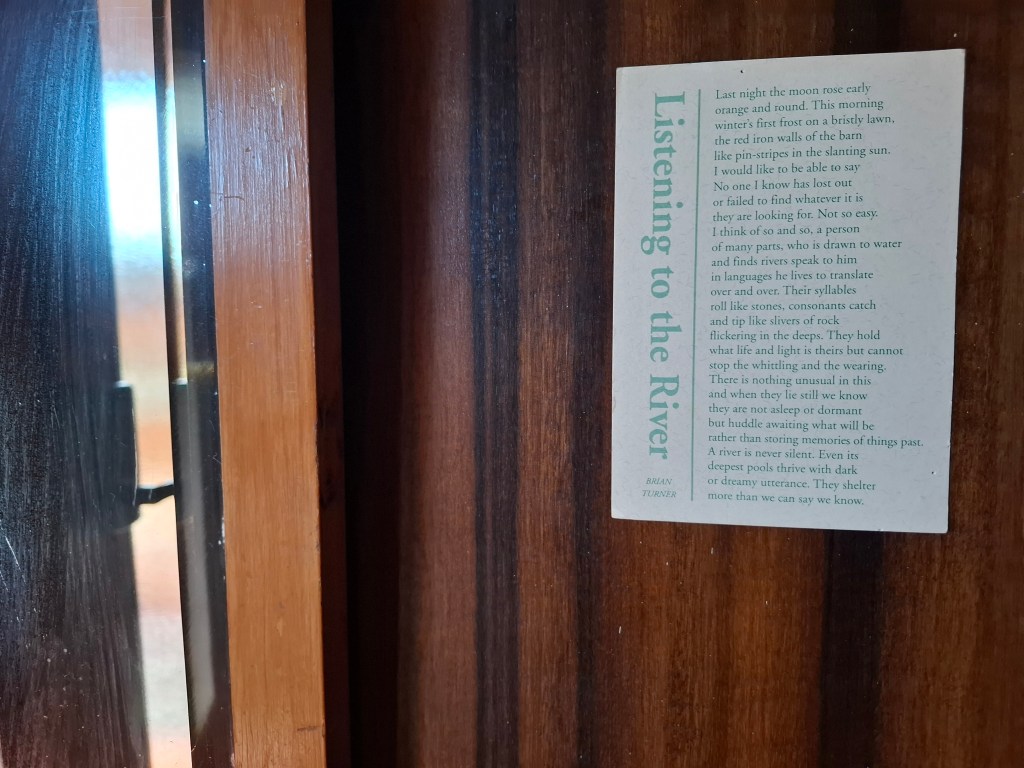

Listening to the River

Last night the moon rose early

orange and round. This morning

winter’s first frost on a bristly lawn,

the red iron walls of the barn

like pin-stripes in the slanting sun.

I would like to be able to say

No one I know has lost out

or failed to find whatever it is

they are looking for. Not so easy.

I think of so and so, a person

of many parts, who is drawn to water

and finds rivers speak to him

in languages he lives to translate

over and over. Their syllables

roll like stones, consonants catch

and rip like slithers of rock

flickering in the deeps. They hold

what life and light is theirs but cannot

stop the whittling and the wearing.

There is nothing unusual in this

and when they lie still we know

they are not asleep or dormant

but huddle awaiting what will be

rather than storing memories of things past.

A river is never silent. Even its

deepest pools thrive with dark

or dreamy utterance. They shelter

more than we can say we know.

Brian Turner, Listening to the River, John McIndoe, 1983

For years, a postcard with Brian’s poem ‘Listening to the River’ printed on it has been blu-tacked to the wall, above the hall table just inside the front door. For years, as I’m rushing in or out of the house, dropping my keys into or grabbing them from the key-bowl on that table, I’ve clocked in my peripheral vision those green words on the cream card. In the way of things that have been around ‘for ever’, I rarely pause to see it afresh or in detail. But it is there, a green river of a poem, the quick sight of it always a cooling moment, a reminder. A reminder of what? Of rivers, obviously, and for me of a particular river, the Manuherikia, carving its ancient path through Central Otago, near Brian’s home in Oturehua. Every so often over the years, keys in hand, I’ve stopped on the banks, as it were, of this poem to read it closely again, word by word, and every time I’ve done this it has settled even deeper in my heart. Their syllables / roll like stones, consonants catch / and tip like slivers of rock / flickering in the depths. I live on the coast, far from this river. I love many of Brian’s poems, but this one in particular for bringing me close to the river on a daily basis, reminding me to listen.

Sue Wootton