The moon will be here before

I say cheese and crackers and I am wishing

in vain for feather down sleep

It’s almost dawn

There’s a pheasant on the lawn

My mouth is dry

The first light feels magenta

Today I will read Claire Keegan

write a long shopping list

visit the hospital

read Anna Jackson’s poetry

This is not a poem

it is a tree

Paula Green

from ‘The Venetian Blind Poems’

forthcoming The Cuba Press, 2025

2024 has been one of the most challenging years of my life. Yet within challenge and darkness, I find joy and light. Poetry Shelf has held on, is holding on, by a thin thread.

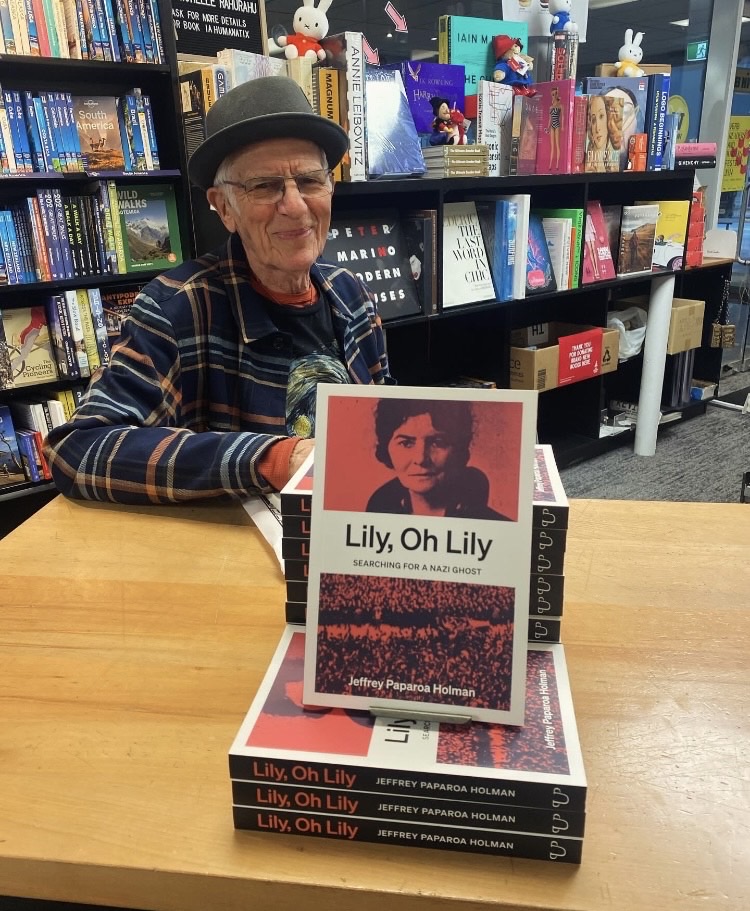

And herein lies the joy. Over the past few years I have replenished my self-care kit, inventing aids to take along my spiky road. There is nourishment in simple tasty cooking, tending a vegetable and herb garden, reading books for both children and adults, especially poetry, writing secret things, keeping my two blogs active, spending time with my family, listening to music, following on the coat-tails of my daughter as she went to concerts by The National all over the world, putting the playlist Anna Jackson made me on constant replay, see shows by Michael Hight and Shane Cotton and writing about them.

My fragile immune system has meant I haven’t risked public events, cafe outings with friends, school visits, author tours, poetry readings . . . and that is such a loss. Yet an important part of my self-care kit is to focus on what I can do, on how I can connect with people, friends, writers, readers, in multiple ways. And books, books are a most nourishing form of travel through time and space. To use my daily energy jar carefully. To read at a snail’s pace.

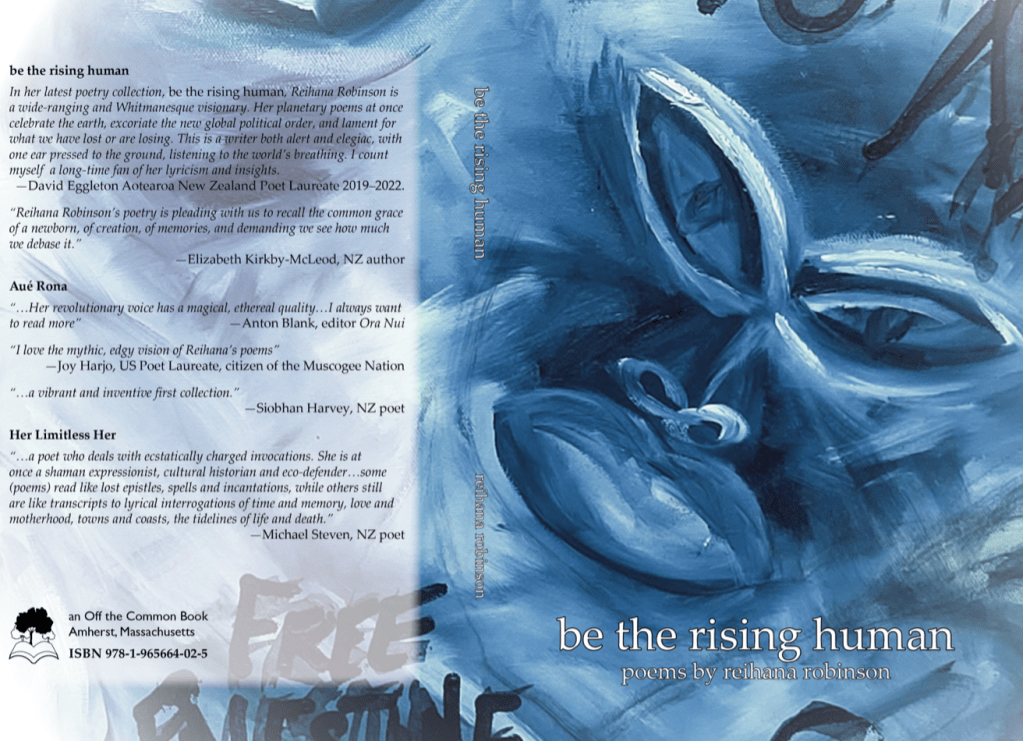

Ah. I still have 30 poetry books published this year in Aotearoa sitting on my desk to read and celebrate over summer. I can’t wait! Meanwhile here are seven I have loved. To these I add the must-visit Starling, an online journal for young writers, edited by Louise Wallace and Francis Cooke, with the current help of Tate Fountain, Khadro Mohamed and Nina Mingya Powles.

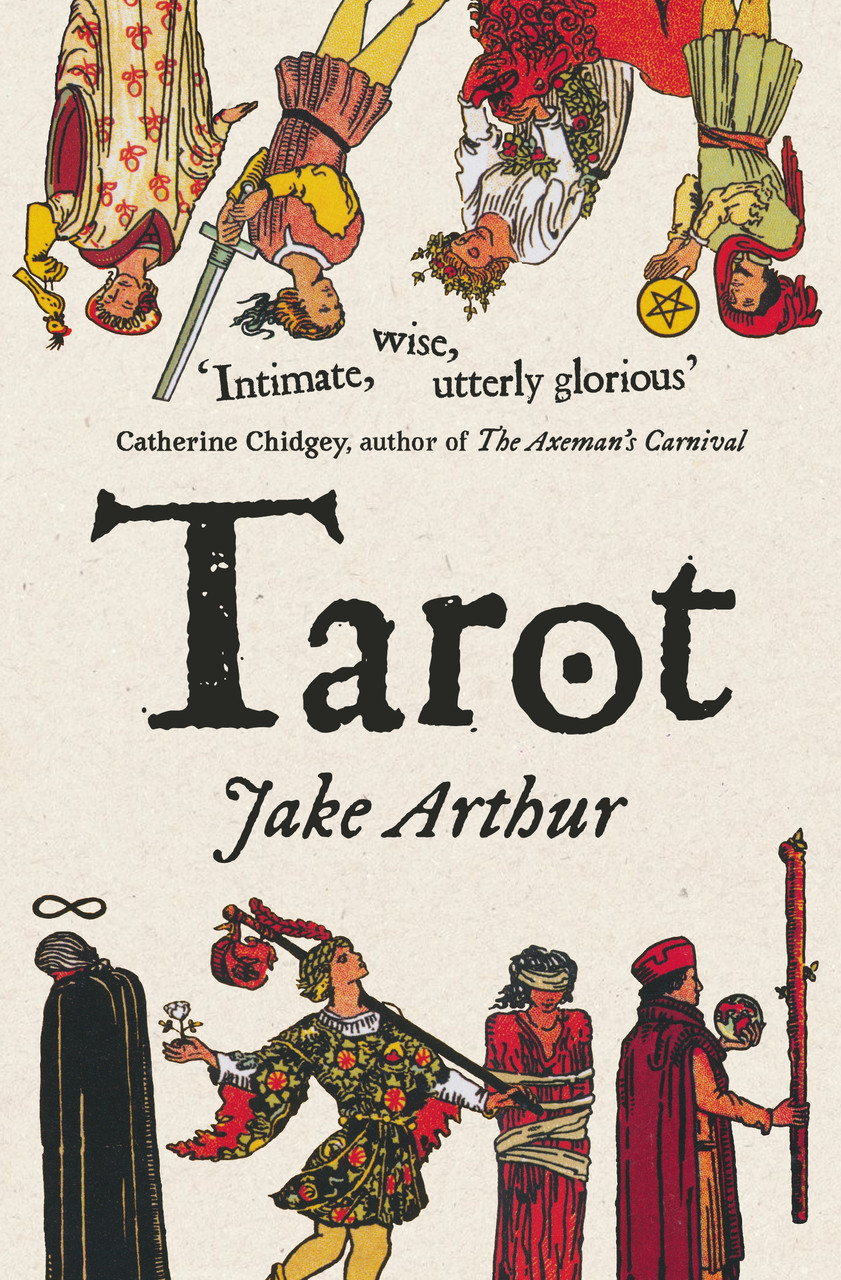

Jake Arthur’s Tarot (THWUP): After my first reading of Jake Arthur’s new collection, Tarot, I wondered how much poetry joy we can imbibe, for reading these poems felt like I was travelling through a solar system of poetry joy.

Dinah Hawken’s Faces and Flowers Poems to Patricia France (THWUP): As she has done across all her collections, she creates moments of stillness where we might enjoy miniature residencies. She writes with such craft and wisdom, with such nuances, richness, quietude. Every book she writes, reminds me why poetry matters. And this gift of a book is no exception.

Rex Letoa Paget’s Manuali’i (Saufo’i Press): To travel slowly with this sublime collection is to enter poetry as restorative terrain, to encounter notions and parameters of goodness, fragility, recognition, to link the present to both past and future, to question, to suggest, to travel, to connect. Oh! and Manuali’i has the coolest illustrations.

Kiri Piahana-Wong’s Tidelines (Anahera Press): This is a precious poetry collection, both moving and lyrical, that lets you feel the sting of salt and despair, fragility and resolve, and you know you need to hold life and loved ones very close. I love it.

James Brown’s Slim Volume (THWUP): Slim Volume draws you into the intimacy of letting things slip, of layering and leavening a collection so that in one light it is a portrait of making poetry, in another light the paving stones of childhood. The presence of people that matter glint, and then again, in further arresting light, you spot traces of the physical world. Try reading this as a poetry handbook and the experience is gold.

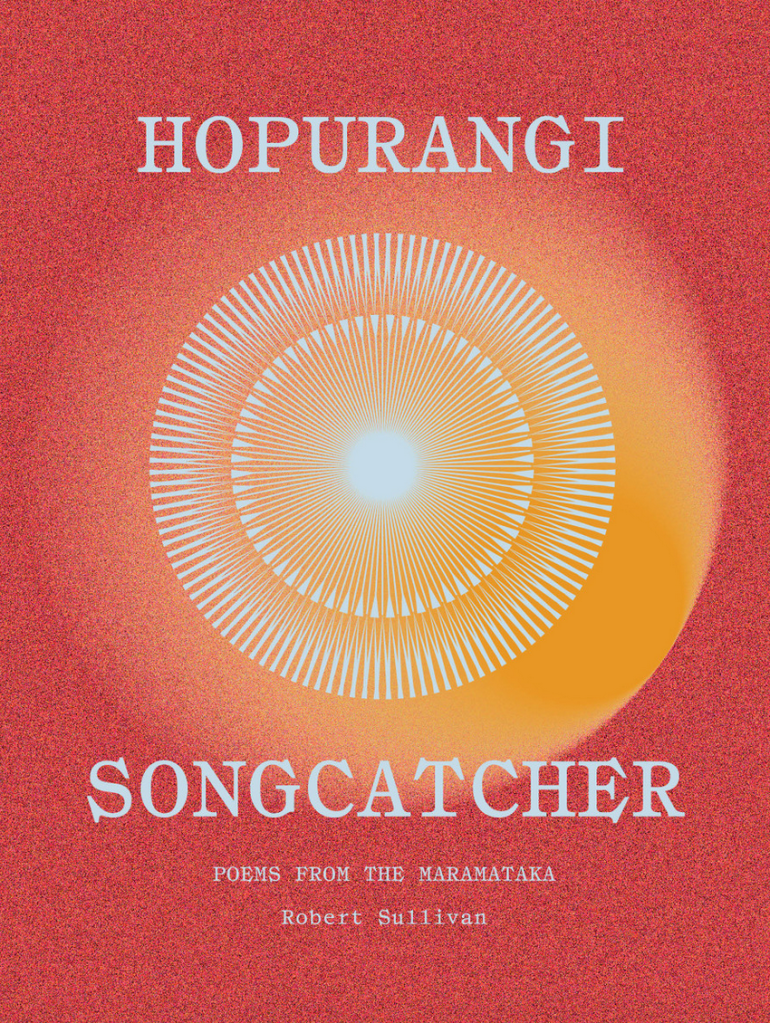

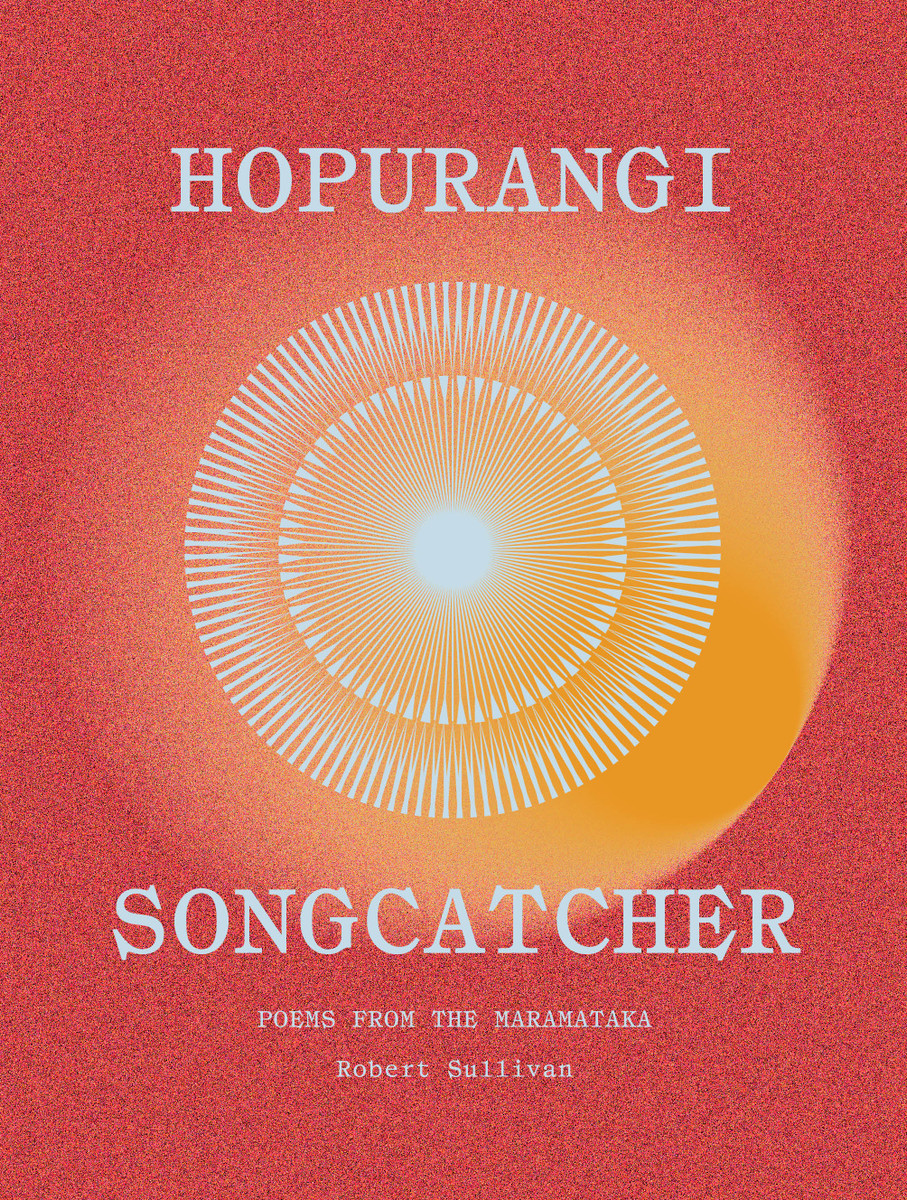

Robert Sullivan’s Hopurangi -Songcatcher Poems from the Maramataka (AUP) resonates alongside the current political edicts, prescriptions and alarming descriptions of what the Coalition Government pledges for the child, the adult and our planet. In Robert’s sublime and breath-enhancing collection, I am finding seeds of hope. Of te reo Māori growing alongside English, both languages vital on our tongues, of tending our relationships, whether human or planetary, with care as opposed to greed, of acknowledging our spikes and our difficulties, of never ceasing to learn new things. I hold this collection out to you as a book of freshness, of reassessing and finding one’s place, a book of experience, wisdom, friendship, hope. And above all, a book of aroha.

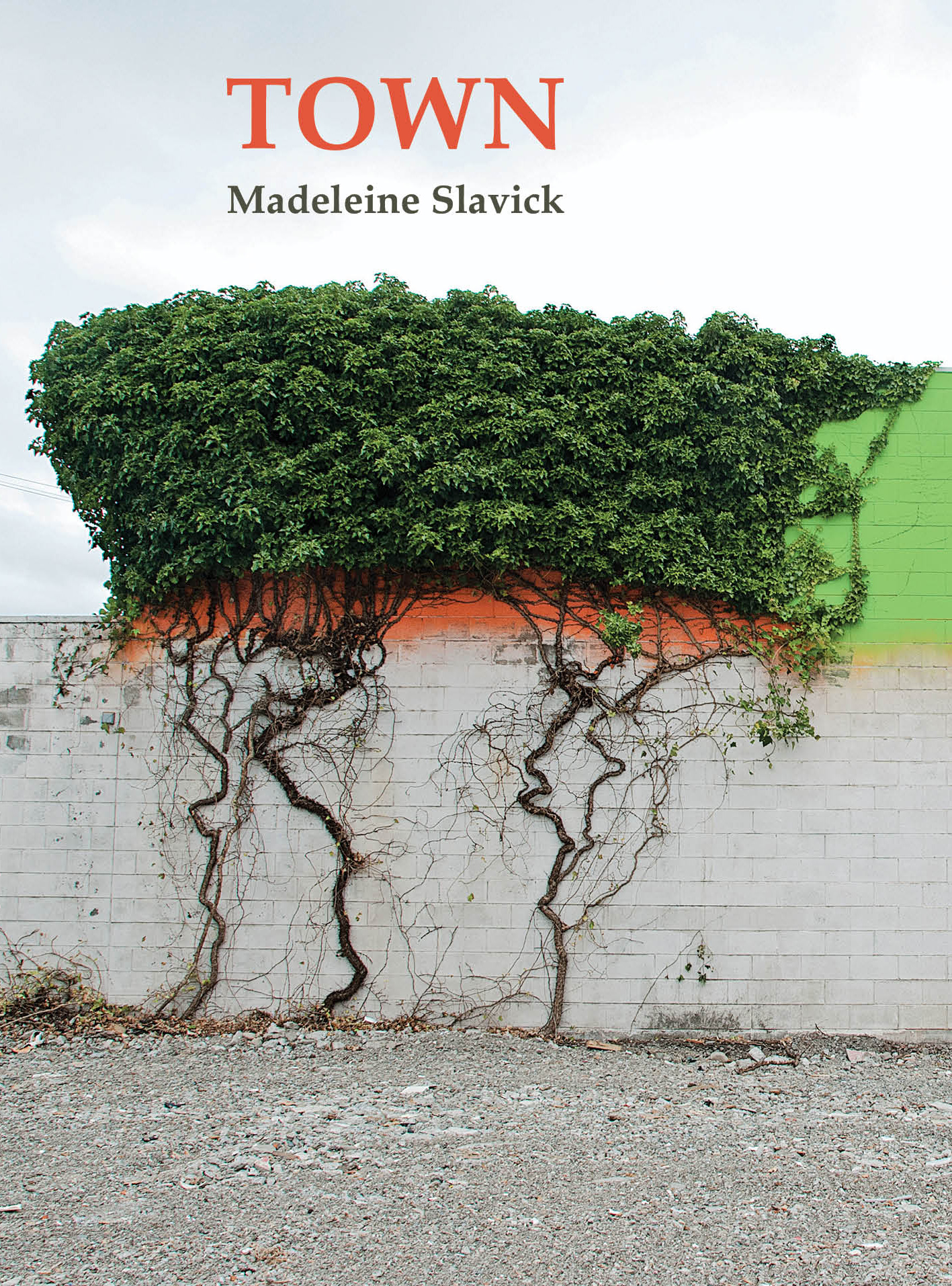

Madeleine Slavick’s Town (The Cuba Press): On the back of the book, Hinemoana Baker nails her endorsement: ‘Town is reminiscent of Robert Hass at his most beautifully imagistic, or Georgia O’Keeffe telling deep stories in flowers.’ Yes this a book to fall into, to savour the joy of contemplation, to recognise the ugly, the surprising, the familiar. It is a book of wonder.

Airini Beautrais‘s The Beautiful Afternoon (THWUP): I have been delving into this sublime book all year. A book of essays, the book engages with life and difficulty, resolve and multiple fascinations, including poetry and reading, on so many levels. It is on my blog list of summer celebrations.

Yes, I have read wonderful books of multiple genres, but the emails you have sent, so thoughtful, warm and empathetic, have also been a vital connection. Poets have contributed to Poetry Shelf so generously, responded to posts, and contributed to the buzz of poetic activity in Aotearoa, in print, online, in performance spaces, in collaboration and going solo.

An ultimate highlight of 2024, was working with Jillian Sullivan and Peter Ireland to create a feature celebrating Brian Turner’s award, the NZ Poet Laureate of Nature. Last week, Jillian sent Peter and I an extract from her journal which describes a river-bank moment. She and Brian read our post, and the poems we had chosen, together. It is an utterly moving image, so comforting. Jillian has given permission for me to include it here. Because this is what matters. The ability, let’s say power, of poetry to make connections, with aroha, with windows opening on the world, on who we are and who we might be.

It is fitting, too that, Anuja Mitra recounts vital moments of connection in what has been a difficult year across the globe.

I finish this post, and Poetry Shelf 2024, with the verve and inspiration of Rachel McAlpine: “Roll on 2025, when I’ll be taking poems into other unexpected places.” Here’s to all of us nourishing the scope and possibilities of poetry in Aotearoa in 2025.

May you all have a safe and replenishing summer. Poetry Shelf is taking a break for three weeks and will return with a Summer Season of Readings and Reviews, to be followed by another series of themes, more Monday poems and features, poetry news, and new ideas.

Poetry Shelf 2024 Highlights Collage – part one here

Poetry Shelf 2024 Highlights Collage – part two here

Jillian Sullivan

Yesterday I walked into Brian’s care home for the first time in 12 days. The week away in Nelson with grandchildren. And then the days of gastro sickness, driving to Riverton, longing to lie down in the grass beside the road. On Thursday, 48 hours after the last symptoms, I walked up the hall at Longwood and saw Brian’s distinctive long lean shape curved in a chair in the lounge, hat on his head, in a group playing scatter ball. I touched his shoulder, watching his face to see if he still knew me. He looked up and his face opened. The caregiver smiled to welcome me, and gave Brian his last turn. He bowled six balls in a row into the number ten hole. The woman and residents cheered. Then he missed a high score at the end, and pretended to kick at the box of balls and made people laugh. He seemed so at ease, that this has become familiar to him, to come and play a game and to react with people, to be competitive and enjoy that. We walked to his room for I had his new dressing gown and a jacket and jersey extra for him. Do you want to come out for a drive, to a café? I asked him. Yes!

We drove up town but the café was shutting so we bought take away black coffees and sat by the sea, sheltered by a concrete wall. I told him about Paula Green’s blog and then brought it up on a phone to read to him. He read Taeiri Days, the poem I chose, and Deserts for Instance, and I read the comments Peter, Paula and I had made about his poetry and he was affected and grateful. Wow, he said.

But to sit there, our shoulders touching, the wind and sea behind us, the footpath in front , people walking by but out of earshot, and three boys sitting on a train carriage mounted just along from us, waving to cars and cars honking back at them. In the midst of that life, Brian read his poems with such cadence and love of the language, as if it was a poetry reading to a writer’s festival, but instead it was just me, and the wind, that preciousness of hearing his words in his voice. Hearing him read once again, by a footpath.”

Anuja Mitra

2024 was difficult in ways I feel too tired to recount, and I’m far from the only one who feels this way. I want to recount instead the moments of connection, of joy and community, when people were brought together by shared passions. There was my small Tāmaki Makaurau writing group that met monthly, armed with constructive feedback and a common drive to make headway on the projects that were plaguing us. We marked the spring equinox with a picnic enjoying the nicer weather and scrawling poems in the park with chalk (from Emily Dickinson to Sappho to Mary Oliver). There were the lovely, generous audiences at the readings I attended at The Open Book for the 110th issue of takahē and Time Out Bookstore for National Poetry Day. There was the immense and enthusiastic audience I (a rare concert-goer) was part of at this year’s Hozier concert — bonded by a love of music, or maybe just something interesting to do on a Wednesday night. I had never really considered the effect of thousands of tiny phone flashlights in a dark room, but then everyone had their hands up and the arena was brighter than daylight.

Erik Kennedy

In a year of precarity and bleak outcomes in the world of arts funding, my highlight is the successful Boosted crowdfunding campaign run by the Canterbury Poets’ Collective, of which I am a committee member. When an eggplant is a fiver and housing is a luxury good it seems mad to ask people to dig deep to support the next five years of live poetry programming in Ōtautahi Christchurch—but they absolutely did. We exceeded our target of $20,000 with pledges from longtime attendees, new friends, distinguished former guests from around the motu, and anonymous heroes. This funding allows us to pay the poets who come perform for us what they deserve to be paid. The whole process was a humbling and affirming reminder, if a reminder was needed, that poetry is much bigger than any of us, and that it clearly fills a need in our communities.

Claire Orchard

Most of us have favourite teachers, don’t we? Miss Grant, at Waterloo primary, I was sure was the cleverest, kindest person I’d ever meet. A few years later, Mr Gledhill was the one to quietly and irrevocably convince me that an understanding of history was not in fact, as my fifteen-year-old brain had decided, a total waste of time. Of course, books can be great teachers too. This year I picked up the novel The Tidal Zone by Sarah Moss (Granta) in an op shop and found I couldn’t put it down until I’d reached the last page. David Nicholl’s midlife romance You are here (Hodder & Stoughton) is feelgood and hope filled, while Sarah Tarlow’s forthright and utterly shattering memoir, The Archaeology of Loss, was quite simply a privilege to experience. More recently, I’ve been revisiting Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet (Serpent’s Tail), the diary of a fictional assistant bookkeeper living in Lisbon during the early part of the twentieth century. A collection of contemplations on the mystery, terror and weirdness that goes with being human, I find I can never read too much of it in a sitting, and doubt I will ever actually reach the end of it, but this is a large part of its charm. Journalist and poet Yanita Georgieva’s wonderful poem Posh Salad, voiced from the brink of parenthood, led me to her excellent pamphlet Small Undetectable Thefts. And I’m ending the year with Te Whanganui-a-Tara poet Jo McNeice’s recently published Blue Hour (Otago University Press), this year’s winner of the Kathleen Grattan Poetry Award and a phenomenally good, deeply original collection. Here’s to more great books, kind and wise teachers, and more humanity, next year.

David Eggleton

I managed to read a bunch of books this year in somewhat chaotic, random Tristam Shandyesque fashion, swooping hither and yon, through the Gutenberg Galaxy and still believing in the primal power of the printed word in the form of actual ink-and-paper artefacts, like some kind of internet heretic. Books pile up like rubble at blitzkreig speed everywhere you look these days, either from built-in obsolescence as bookshops off-load stock to make way for more stock, or because book hoarders are dying off and relatives are dumping their libraries in recycling bins. So many books, so little time, that books rely on word of mouth or enticing blurbs — or is it reviews on Amazon? Oscar Wilde wrote of one book: ‘There were metaphors in it as monstrous as orchids and as evil in colour. The life of the senses was described in the terms of mystical philosophy. One hardly knew whether one was reading the spiritual ecstasies of some medieval saint or the morbid confessions of a modern sinner. It was a poisonous book. The heavy odour of incense seemed to cling bout its pages and trouble the brain.’ Who wouldn’t want to read that book. It is of course, Against Nature by J.K. Husymans, and once upon a time everybody had read it or wanted to read it, to savour the incense of its pages. Nowadays, not so much.

Instead, we get something like: ‘The laptop, having slid off her chest as some point in the night, lay dead and open beside her when she woke around midday. In the bathroom down the hall, Elsa sat on the toilet and grabbed her phone, which she had placed moments prior on the counter’s ledge.’ Thus, Madison Newbound in her 2024 novel Misrecognition (Bloomsbury).

Totally the age of screens, and totally anathema, and yet here we are. Blame our tech bro overlords or blame Kindle, or blame Nietzche, who wrote in Ecce Homo: ‘To get up in the morning, in the fullness of youth, and open a book. Now that’s what I call vicious!’ Novels — to stick with just novels, because I’m currently judging poetry for the 2025 Ockham Book Awards and need to mind my P’s and Q’s, or have them minded for me — I rescued from various remaindered shelves or op-shop back-rooms this year included Olivia Manning’s The Great Fortune (Penguin), first published in 1960, a shrewdly observant semi-autobiographical story about British Council employees stranded in Romania at the start of World War Two. (Manning’s The Balkan Trilogy and The Levant Trilogy are well worth seeking out.) Another great find was Randolph Stow’s The Merry-Go-Round in the Sea (Penguin), from 1965, an extraordinary novel about the end of childhood set in pastoral Western Australia. It’s extraordinary not only in convincingly recreating the moodiness of the World War Two era, but also in conveying the fatalism of an Australian soldier who had been held in Japanese POW camps, after he returned.

And now to nominate a few more recently-published reading highlights. A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: A Palestine Story, by Nathan Thrall (Penguin, 2023) has been overtaken by apocalyptic events, but this story of how Palestinian children who were injured in a bus accident were treated by Israeli authorities, laid out in careful and horrifying detail, is really testament to what precipitated the events of October 7th, 2023. The Palestinian people, living more or less in a state of permanent incarceration, where you could be shot and killed for looking at an Israeli settler in the wrong way, were goaded into an impossible position.

Grey Bees (Quercus Publishing, 2021) is a novel by Andrey Kurkov set in the period after the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and the start of the war in Donbas in Eastern Ukraine, and conveys vividly the sense of living in a twilight zone by telling the story of a solitary bee-keeper just trying to look after and protect his hives, while a war swirls around him, involving an array of curious characters including assorted loyalists, separatists, Russian occupiers and Crimean Tatars.

Oppositions: Selected Essays, by Mary Gaitskill (Serpent’s Tail, 2021) is wonderfully contrarian about a variety of topics, including Norman Mailer as macho man and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn: ‘Gone Girl… evokes what has become a cultural ideal of relentless feminine charm tied to power and control.’

The Backstreets: A Novel from Xinjiang, (Columbia University Press, 2022) by Uyghur writer Perhat Tursun, written before he disappeared into a concentration camp in China, is saturated in a brilliantly-rendered Kafkaesque or Borgesian atmosphere of foreboding and paranoia in the fogbound endless streets of a vast city.

This year I read Charlotte Wood’s comic novel The Weekend (Allen & Unwin, 2019) about three septuagenarian women friends who were golden girls of the 1960s meeting up for a beach-side holiday, and was so taken by its caustic wit about the ageing process that I immediately got hold of her Booker prize short-listed Stone Yard Devotional (Allen & Unwin, 2023), only to be bemused by its weird Catholic subtext. Weird because although it’s not overt, this is absolutely a novel about sectarianism reaching out from the author’s own childhood to encompass and smother. The result is dour, worthy and earnest— though the mouse plague while typically Australian is also fantastically surreal.

Quntos KunQuest’s This Life (Agate Publishing, 2021) is a rap-novel in musically cadenced language about day-to-day life in goal and personal coping strategies, by someone locked up in Angola Penitentiary in Louisiana since 1996. Though the writer doesn’t play down his drug-related offending, it is obvious that his prolonged imprisonment is disproportionate, but that also it is highly typical of a large number of fellow inmates, who are caught up in legislation designed not to rehabilitate them but to keep them locked up. The Canadian author Cory Doctorow elaborates on this subject in his novel The Bezzle (Macmillan, 2024), which is about private prisons in California, ‘enshittened’ by private equity. As a character in The Bezzle puts it: ‘We are living in a golden age of grift. We just put a guy in the White House who brags about his criminal acts, says they “make him smart”. When it comes to embezzlement, he’s King of the Bezzle… People today, they think the government can’t do anything right, so they want the private sector to take it over. Then, when someone like this Thames Estuary outfit comes along and starts stealing everything that isn’t nailed down, those same people are like, “You see? I told you the government was incompetent.”‘

I had better stop, but I just want to mention the novel At the Grand Glacier Hotel, by Laurence Fearnley (Penguin, 2024) because it’s about proprioception, or the body’s ability to sense movement, action, and location. This ability present in every muscle, and without proprioception, you wouldn’t be able to move without thinking about your next step. Fearnley’s novel explores this fascinating topic using her own personal experience following major surgery, but the subject is also part of a set of novels about the body’s senses, of which this is the third. The sequence is shaping up to be a major achievement.

Michelle Elvy

Ōtepoti Dunedin is alive with creative energy – you just have to step outside to find something happening, from independent zines to theatre to music. And there is always room for emerging voices in our literary landscape. A lot of this happens in Dunedin with energetic support of Nicky Page and her team at our UNESCO City of Literature. And 2024 was a year of collaborations.

2024 was a year of collaborations for me. Working across platforms and genres opens up new spaces for creative exploration, and each time any expectations I have going into the project are far exceeded by the results. The Arts + Science Exhibition in Ōtepoti Dunedin was a highlight, with some 50 people collaborating to present artistic-scientific representations of memory. It was a real buzz meeting regularly between February and July with Manu Berry (printmaker) and Rachel Zajac (psychologist) – discussing, experimenting, shaping our project. We invited Cilla McQueen to participate, and together we created memories in wallpaper: graphic, tactile, poetic. Our work was shared on Poetry Shelf in July.

Fireworks with Cilla’s words

One thing leads to another. And besides the wonderfully inspiring work from this project, my poetry series ‘The map in your palm’ was runner-up in the Kathleen Grattan Award for a Sequence of Poems. The sequence deals with navigation, parenting and our natural world. A handful of the poems in this sequence had their start with the memory work I did with Manu and Rachel for the Art + Science programme. Here is the small poem that holds the title to the sequence:

Memory

holds you aloft, blows wind in your sails

knocks you sideways, calls up the dead

your lat and long, your yin and yang

this compass to guide you, your daily bread

these stories, these waypoints

the then and the present

those edges, this centre

the map in your palm

This poem indicates a way of navigating all kinds of seas, rough or calm. Stories, waypoints, poetry – these are our guides. In a year of such tumult and uncertainty, globally and locally, creative collaborations keep the spirit alive. May there be many more ways for artists and creative voices to keep moving forward in 2025.

Tusiata Avia

Highlights in a Low-high year

Weirdest year ever. Weirder than the year I woke up on the floor, forgot my name and what country I was in.

Year two of being crushed-on-hard by David Seymour aka Fashweasel aka Temu-Himmler aka No-such-thing-as-white-priveldge aka Colonisation-didn’t-happen. David and his spokesperson for the Arts, Todd Stevenson, aka Never-read-a-book-of-NZ-literature, have- followed-my-every-move- like-stalker. They never passed up an opportunity to bully me. I win the PM award for literature (poetry), next day they’re calling it a “sick sick” decision and throwing threats around all over the place.

(Umm, I can tell you what is sick: their vile Treaty Principles Bill!)

New years day 2024 they’re posting the same thing again – telling the world I won $60K for one poem.

Wouldn’t it be awesome if one poem would earn me $60K? The PM award is for a ENTIRE CAREER, which would work out at about: 60K divided by 25 years divided by 52 weeks equals forty six dollars a week . Forty six dollars a week for being good at my job, not sixty thousand dollars for one poem. But, why would the Art spokesperson know that?

This has been the weirdness: every time something good happens: Show premier, PM award, Senior Artist Award – these sickos are pouncing like . After years of poor followed by poor and some more poor, I’ve hit year 20-something and some of my hard working chickens are coming home to roost. And it is knives out from these men: chase the chicken, tell everyone how bad the chicken is.

I think they want to eat the chicken.

Kay McKenzie Cooke

2024: More Highs Than Lows

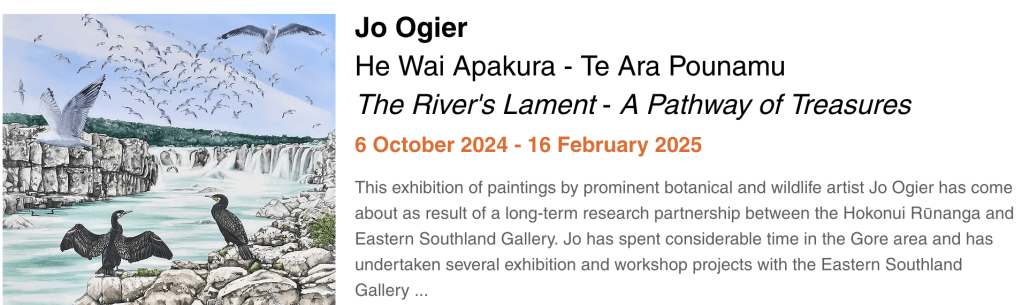

Jan: New Year in Kakanui—cutest small town in NZ. Feb: Sunflowers & ice creams from the dairy. Queenstown: wine, roses, mountains & lake. March: Ōepoti: J&K photo shoot with Clydesdale. April: Japan: crows, canals, trains, cherry blossom & piles of old snow. Taipei: a gondola ride up a mountain & a typhoon. Singapore: the smell of the effect of humidity on deep green. May: Auckland: Sky Tower skyline & Waiheke Island ferry. Russell: blue water, pohutakawa & history. Whangarei: the clock museum. June: Invercargill: out loud poetry with Jenny P. & David E. & Dan D. Aparima / Riverton: the whale. Ōtepoti: Tim Jones’ Weather Event. July: Queenstown (again): family off to Germany. Wellington: Cable car. Horowhenua: Lazy Square, a whānau hui. Wairarapa: Sisters Roadie, wine, book shops & crockery. Aug: Ōtepoti: 6 movies at Regent Film Festival; best 2, ‘Head South’& ‘Outrun’, worst 1, ‘Janet Planet’. Sept: Bluff: port, poetry, writing, weather & Cilla. Timaru: Caroline Bay at dusk, officious penguin lady & farewell to the last of my aunties. Waimate: a bargain poncho. Ōtepoti: Larnach Castle: scones & jam, red kaka beak flowers & pepper trees. Oct: Queenstown (again): airport & family back from Germany. Waihola: boardwalk across the lake. Catlins: waterfalls. Kaka Point: wind. Gore: Bro-in-law’s birthday dinner at Mr Green’s. Nov: reading through all of ‘Te Awa o Kupu’, having the Dolans in Dunedin. Tairoa Head: Katherine & seagulls & bull kelp. Dec (so far): baking cup cakes for moko, rata in flower, reading Talia’s book. All year round constant highlights: whānau, writing, drinking tea & not watching TV News.

Airini Beautrais

It’s always hard to pick favourites, but here are some things I have enjoyed in 2024.

In poetry, I really loved Kiri Piahana-Wong’s poem sequence Tidelines (Anahera Press). It is a moving combination of the story of the historical figure Hinerangi, with personal narrative. I also loved Robert Sullivan’s Hopurangi: Songcatcher (Auckland University Press), another book-length poem sequence, focusing on the maramataka. I like the ways in which Robert merges the cycles of nature with personal experiences and observations.

In fiction, Lauren Keenan’s The Space Between (Penguin) is an entertaining read, set in the Taranaki wars. Lauren is very good at telling an engaging story that also honours the realities of historical events. Also set in Taranaki, but more recently, is Airana Ngarewa’s Pātea Boys (Hatchette), a collection of short stories. These stories were a lot of fun, and I appreciated the local setting.

A film highlight of 2024 was the short film Finding Venus, directed by Mandi Lynn, which I saw in the DocEdge film festival in Wellington. I have a personal connection to this film as I was one of the ‘golden shieldmaidens’ back in 2018, and have a short cameo. It has a globally relevant message and is currently touring international festivals. If you see this film, take tissues, because you will cry.

My favourite TV series of 2024 was Rivals (Disney), based on a Jilly Cooper novel. It’s very 80s, very political incorrect, and David Tennant is an excellent villain. I loved the soundtrack, the wardrobe, the hair. I watched it twice. I really need series 2 to be made!

In the visual art world, it’s been exciting to have Te Whare o Rehua Sarjeant Gallery reopen in Whanganui after a long earthquake strengthening and extension project. I encourage everyone to visit Whanganui and visit the Sarjeant, where the current exhibition ‘Nō Konei | From Here’ is like a greatest hits of the collection, featuring many local artists and artists with connections to Whanganui. I was honoured to be asked to write a poem for the publication Edith Collier: Early New Zealand Modernist edited by Jill Trevelyan, Jennifer Taylor and Greg Donson. It’s a really beautiful book featuring a lot of Edith’s art. She had a fascinating life story too.

Helen Rickerby

In recent years I’ve mostly been reading, and getting inspired by, creative non-fiction, but this year I have renewed my appreciation for the novel – the special things it can do, including things that push the boundaries of what I thought a novel could be. I had a rather significant birthday this year, and one of my gifts from a friend was All Fours by Miranda July (Canongate). I loved it! I loved it in the way you love something that resonates with you, and just a little way in I exclaimed to myself ‘This is why we need novels!’ Despite (or maybe because of) its nuttiness, I think it is telling something true, but in a way maybe only a novel can. It was an excellent companion piece with Lioness by Emily Perkins (THWUP) (which another friend gave me for my birthday) and from these two books I can now tell you with authority that mid-life for women is all about dancing, broadening your sexuality, and ceramic lions.

Another novel that was a highlight for me this year is Motherhood by Sheila Heti (Penguin). I had put off reading this for a while, thinking it was just about the narrator (and, being autofiction, also the author) deciding whether or not to have a child (not to say that isn’t an important decision, and in fact the local essay collection Otherhood, in which I have an essay about this very topic, was another highlight this year); and it is about that, but it’s also about so much more than that – relationships, philosophy, religion etc. And the thing that especially inspired me was the author’s engagement with chance (throwing coins to get a yes or a no) in several parts of the book, which paradoxically leads to some really meaningful ‘conversations’. It connected with my own use of randomness and chance this year, and set me off in an (to me at least) interesting direction with my own writing – in my case poetry. (I don’t think I have the stamina for a novel! Or at least not yet.)

I also have to put in a quick word for Intermezzo by Sally Rooney (Faber) – though somewhat different, in my household we agree that she is a great humanist novelist in the tradition of George Eliot. And I was especially taken with the way the narrative voice/internal monologue for one of the characters (Peter) read to me like poetry in its fragmented, repeating style. Though maybe I am just looking for poetry in all literary forms.

Rachel McAlpine

It’s almost 50 years since Caveman Press published my first book of poems, Lament for Ariadne. I could never have predicted the highlights of my 85th year! This year I jump-started a podcast that had stalled, renamed it Learning How To Be Old, and upped the stakes by including guests and street polls. That’s very exciting from my point of view. I see the podcast as half creative toy, half public service. I’m slowly acquiring the nut and bolts of podcasting — legal, logistical, strategic, interpersonal and technical. Other highlights have been three conferences: Age Concern New Zealand, NZ Association of Gerontology, and Faculty of Psychiatry of Old Age 2024 Conference RANZP. I’ve loved speaking there as an old poet, representing their client base, with poems in my pocket. Roll on 2025, when I’ll be taking poems into other unexpected places.

Paula Green