Welcome to an ongoing series on Poetry Shelf. I have been thinking a lot about the place of poetry in global catastrophe and the incomprehensible leadership in Aotearoa. How do we write? What to read? Do we need comfort or challenge or both? I am inviting various poets to respond to five questions. Today, poet Isla Huia.

1. Has the local and global situation affected what or how or when you write poetry?

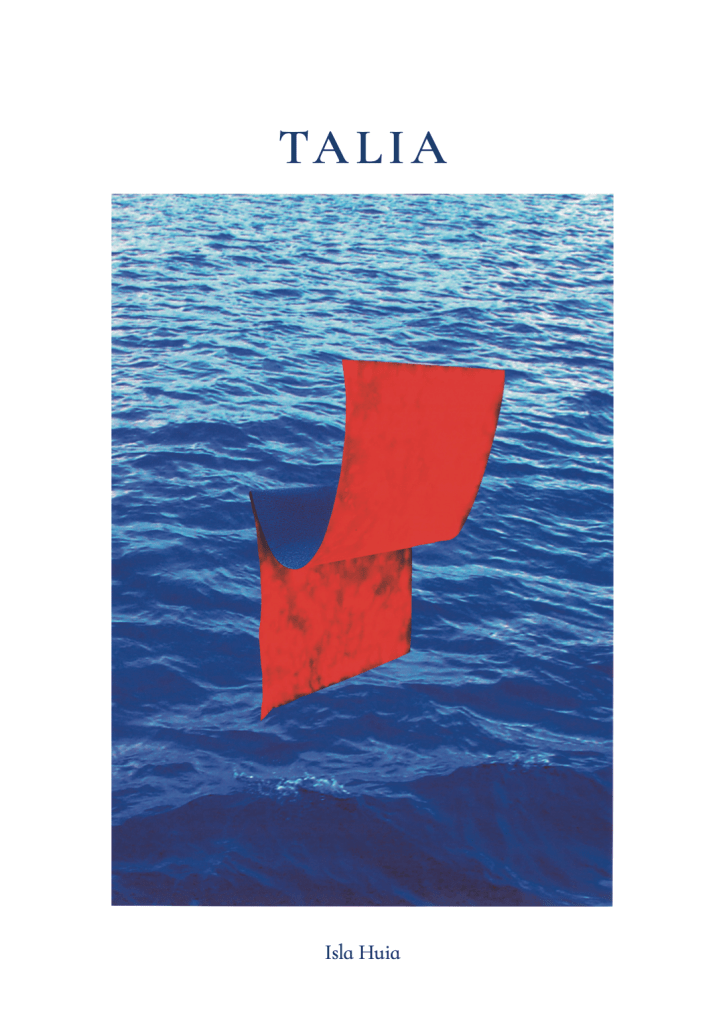

Absolutely, totally, overwhelmingly; yes. When reflecting on the poems that made up my book, Talia, I notice now how many of them came from the perspective of a response, a review, or an observation. Writing is the avenue by which I express my reactions to the world around me; it always seems like the most natural way for me to express myself, and to answer back to what I’m seeing in the world. Indigeneity has always been a key theme in my work, and now more than ever, it feels vital to provide a counter-narrative to the one we’re hearing from our so-called leaders, and to openly and courageously (albeit on paper) hit back at it all with some home truths. Obviously, there’s more going on than just the blatant racism in the political sphere – the daily assaults on papatūānuku, the daily assaults on our diverse communities, and of course, the daily atrocities we’re seeing being experienced by our Palestinian brothers and sisters. It’s too much to hold in my body, so really, it feels like I have no other choice but to get it out through my words.

2. Does place matter to you at the moment? An object, an attachment, a loss, an experience? A sense of home?

Place is fundamental for me. In a Māori sense, the most important things in my world are people and places, and everything else comes as a byproduct. Similarly to what I was referring to earlier, I didn’t really realise how much of Talia was focused on places until I looked back on it, but now I see that the book itself is really a map between the locations and the lives of people who are crucial to me. Te Henga, on Auckland’s west coast, featured a lot, as did Whanganui and Motuoapa and the places I whakapapa to. So did Ōtautahi, and Te Kiekie Mount Somers, and so many of the places that I’ve been called to write in, or about. I spend a lot of my time walking, and when I’m not at mahi I’m usually either reading, or tackling my ever-growing list of tracks and places to explore here in Waitaha. And when I’m walking, I’m always writing. It’s places, especially quiet and isolated places, that give my body and my head the kind of clarity they need to work together and produce words that are true, authentic and real.

3. Are there books or poems that have struck a chord in the past year? That you turn to for comfort or uplift, challenge or distraction.

Oh, always. I find myself reaching more and more often for either works that hit-home so hard that they make me feel seen, or works that are so far outside of my lived experience that I feel distracted from the actual world we’re living in – or at least the one I’m seeing. Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, A Girl is a Half-formed Thing by Eimear McBride, and Intimacies by Lucy Caldwell are works of fiction that I’ve totally fallen for this year. Haerenga: Early Māori Journeys Across The Globe by Vincent O’Malley, The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein and So Sad Today: Personal Essays by Mellissa Broder are non-fiction books that have challenged me and helped me in all the same breath. We, The Survivors by Tash Aw, The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi, and A Passage North by Anuk Arudpragasam have given me insight into lives so painful, and beautiful, and fundamentally unimaginable to my own. Overall, though, the books I’ve read that have come out of Aotearoa are the ones that I’ve clung to, and the one’s I’ll always remember for their familiarity, their relatable ache and the way they remind me of something I can’t name but always need: Tangi and Into The World of Light: An Anthology of Māori Writing by Witi Ihimaera, Loop Tracks by Sue Orr, Bird Child and Other Stories by Patricia Grace, 2000ft Above Worry Level by Eamonn Marra, Plastic by Stacey Teague, Faces in The Water by Janet Frame …. to name but a few.

4. What particularly matters to you in your poetry and in the poetry of others, whether using ear, eye, heart, mind – and/or anything ranging from the abstract and the absent to the physical and the present?

He pātai pai tēnā. For my own writing, I aim more for heart, mind and wairua than ear or eye. I want my writing to physically move me back to the place, circumstance or perspective I was in when I wrote it. I want it to feel entirely tika, and raw, and I want to understand myself better for having written it. Sometimes, that doesn’t translate onto the page, or feel palatable or decipherable to an outside audience; but it’s always the place I write from, regardless. How my readers interact with my work is secondary to whether or not I feel like I am entirely, uncompromisingly myself, within it. I guess the same applies for me as a reader, when I think about it. I like books of all genres that emote a certain feeling, or provide an atmosphere, or hold an energy; all of those more abstract things that are hard to pinpoint or describe. I look at words far more than I look at plot, or narrative, or structure. I look for the feeling between the lines more than I look for a perfect description, or a clever piece of dialogue. It’s all in the wairua.

5. Is there a word or idea, like a talisman, that you hold close at the moment. For me, it is the word connection.

I’ve always loved the word ‘remember.’ I have it engraved on the inside of a ring that I’ve worn every day for years. Sometimes I worry that I do too much remembering (stewing, over-analysing, regretting…) that I’m stuck in the past, but I also think that my love of remembering is where my poetry comes from. The name ‘Hinewai’ is a bit of a talisman for me too. It was the name of a whole line of my tūpuna wāhine and is definitely the name I’ll give to a pēpi one day. It translates to ‘girl of the water’, which makes sense, being that we hail from the banks of the Whanganui river, and the Manganuioteao tributary. Oh, and my aunty Alice read my tarot cards last week and almost all of the cards were cards of ‘cups’, which she said signified emotion, connection and relationships. So that’s a bit of a tohu, too. And so are aunties – thank god for them.

korowai

in the back of aunty’s whip

makawe rewilding in the hau

hands on hot plastic we are

precious in the cargo trailer

and i think, i want to be telling

my nephew to put down the

fishing rod and mihi atu ki a whaea

for the rest of always,

i wanna go out telling him

‘it’s an urupā not a flower farm’ and

that i have comeback to see the dead

in my grass rash the gods in my genepool

the fruits in my fat

i want this land to return me dirty

and sodden, to de-extinct me

from the birdbones out

i want my river to whāngai me

backwards as in, i wanna come through

this place to find there is no otherside

other than this one.

Isla Huia

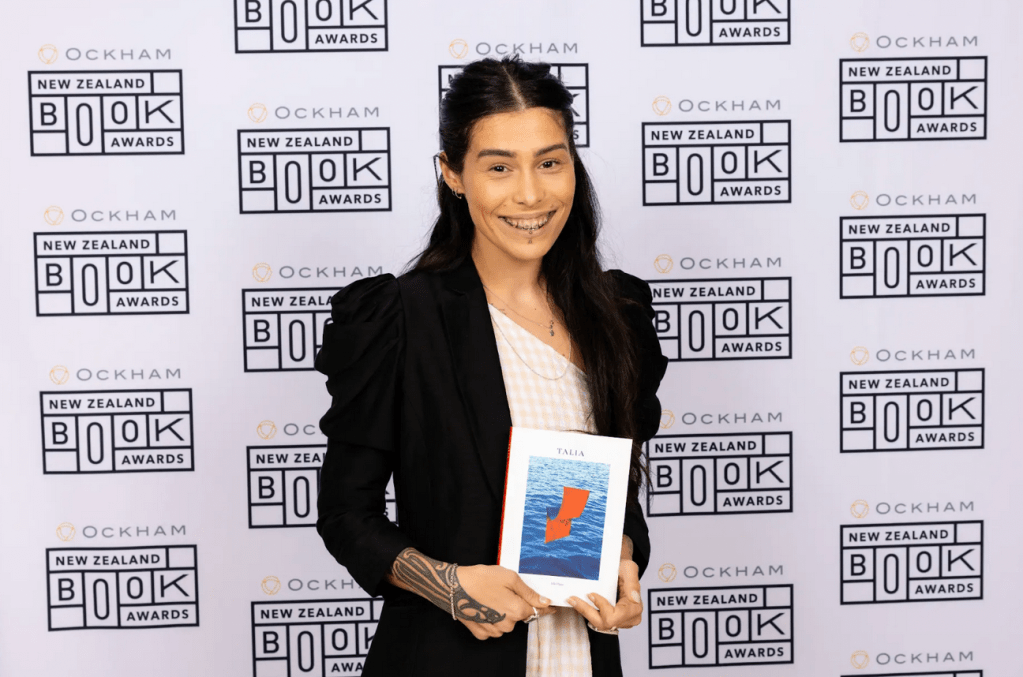

Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku) is a te reo Māori teacher and kaituhi from Ōtautahi. Her work has been published in journals such as Catalyst, Takahē, Pūhia and Awa Wāhine, and she has performed at numerous events, competitions and festivals around Aotearoa. Her debut collection of poetry, Talia, was released in May 2023 by Dead Bird Books, and was shortlisted for the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards 2024.

Dead Bird Books page

Pingback: Poetry Shelf newsletter | NZ Poetry Shelf