Even if we don’t know its name:

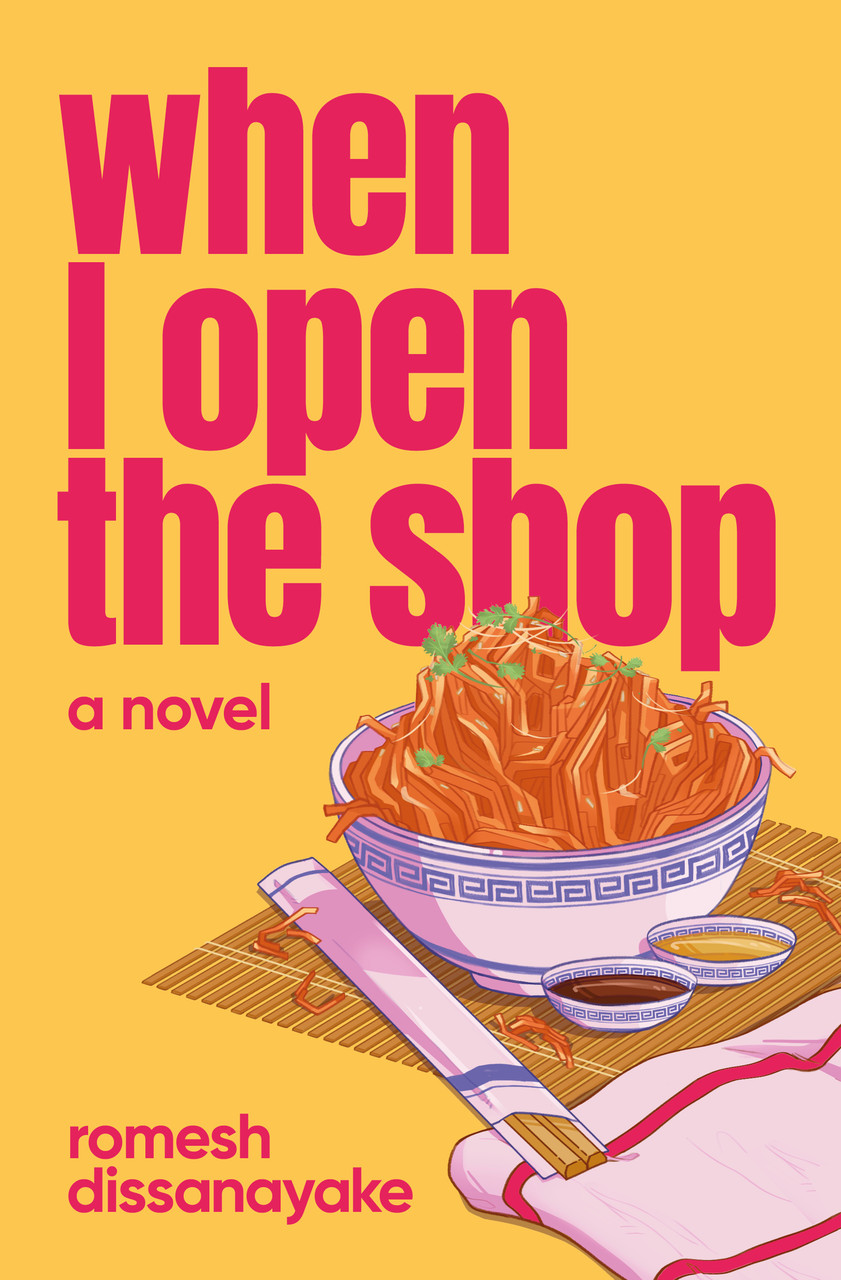

On poetic form in romesh dissanayake’s novel When I open the shop

(Te Herenga Waka University Press, 2024)

I have spent the last few years thinking about the use of poetic techniques in narrative as part of my PhD at the University of Otago, where I wrote my first novel, Ash. On reading romesh dissanayake’s When I open the shop, I was struck by its similar meditations on form. Incorporating poetic elements into prose makes great sense for dissanayake, who writes in both genres (he is one of the three featured poets in the forthcoming AUP New Poets 10), and allows a tension between stasis and movement, as well as enhancing the book’s emotional core. While the narrative drives us forward, dissanayake’s poetic sensibilities allow for a closer view, zooming in to focus on a small moment or musing, then zooming back out again for the narrative push to take over.

The protagonist is a chef, running a small noodle shop in Wellington. As with poetry, cooking is the act of making, where ideally the process is relished as much as the result – a joy or passion that feels palpable in the novel’s craft. When dissanayake draws all of this together and combines it with the protagonist’s personal reflections especially around his late mother, it becomes particularly affecting:

‘We’re going to make morkovcha,’ she says. ‘Just you and me.’ She sets a plastic sheet on the floor and a pink plastic tub of carrots on top. There is a wooden chopping board, worn down in the middle. A knife. A grater. A garlic press.

A container of Cerebos salt with a blue pour adjuster. On the label a boy with a neckerchief chases a chick. See how it runs.

A clear DYC white vinegar bottle. A peanut butter jar filled with coriander seeds. A yellow screw-top lid. A bag of Chelsea white sugar. Everyday sweetness you can enjoy.

I am in bed alone. I am with all of these things. These things I remember.

You can see dissanayake’s poetic hand not only in these descriptive snippets within the novel, but in the structure – the way he uses poetry to make switches between a sense of stasis and movement.

In the middle of the book, ‘The Island’ materialises – an extended poetry sequence. Its sudden appearance feels organic, in a novel that has already established its connection with a poetic use of language. It tells a known myth / a story inserted by the author / something the protagonist is thinking up themselves or remembering – it’s not clear, but it’s also not as important as what the sequence offers.

THE ISLAND

1.

The moon is high.

The sky is freckled with stars.

The island is bright.

Manone wakes from his sleep.

He holds out his hand

and inspects it in the light.

Turning it over, flexing and bending

his long thin fingers,

making shadows slither across the ground.

Next to him, Mantoo is hunched in a ball,

breathing steadily and kicking her foot out.

Her habit to twitch –

to stop herself from falling.

The winds have changed.

Now, it is cooler.

Now, it is harder.

Now that Manone knows it can be collected,

he can never let them run out of salt.

from ‘The Island’ in When I open the shop

‘The Island’ follows straight after a narrative peak, and importantly, it provides a pause – a significant pause that I’m not sure could have been achieved with prose alone. It lifts us out of the immediate narrative of the text and slows the pace down, almost as though we are now in some kind of meditative state, existing on another plane. Movements in the sequence are slow – Manone turning his hand over, flexing his fingers – and the dailiness of survival is at its centre. Like a fable, ‘The Island’ itself is a complete narrative in minature – a story within a story – about a pair’s survival on an island during a storm, and Manone’s quest for salt. In ‘The Island’, and as in any good fable or myth, the narrative tone is suddenly confident, matter-of-fact and acts as allegory. We wonder what connections this miniature story has with the larger narrative. What it might help us to understand. dissanayake does not spell that out either – rather, he allows the poem to enhance particular themes: ancestors and heritage, survival, friendship, our reliance on food, and the joy of taste. In the middle of a novel, ‘The Island’ feels like a song, calling us back to something ancient – that in a state of grief, or in a place we can’t make sense of, might be something solid, something we can rely on, even if we don’t know its name.

Louise Wallace

Louise Wallace is the author of four previous collections of poetry, including This is a story about your mother (THWUP 2023). Her first novel, Ash, is available now.

romesh dissanayake (Sri Lankan, Koryo Saram) is a writer from Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington. His work has appeared in The Spinoff, Newsroom, Pantograph Punch, Enjoy Contemporary Art Space and A Clear Dawn: An Anthology of Emerging Asian New Zealand Writers. His first novel, When I open the shop (2024) was the winner of the 2022 Modern Letters Fiction Prize from the International Institute of Modern Letters at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.

Te Herenga Waka University Press page